![]()

Part I

Citizens’ perceptions on security and privacy – empirical findings

![]()

1 Privacy and security

Citizens’ desires for an equal footing

Tijs van den Broek, Merel Ooms, Michael Friedewald, Marc van Lieshout and Sven Rung

Introduction

PRISMS (PRIvacy and Security MirrorS) is a FP7 project that focuses on the so-called trade-off relationship between privacy and security. The most prominent vision is that security comes with a price, namely at the expense of privacy. One cannot have both, and being secure means that control needs to be exercised over one’s situation, often by third parties who thus need access to the private sphere of citizens. This trade-off thinking is however criticized from a number of perspectives (Solove 2008; Pavone et al. 2012). The criticism points at faulty assumptions that take stated preferences of respondents on face value while these conflict with actual behaviour (Ajzen 1991). It also criticizes the fundamental presupposition that seems to deny that it is factual impossible to have both. Trade-off thinking is a priori framed in a discourse that apparently rejects the possibility that security can be achieved without infringement on privacy (Hundt 2014). This framing endangers democratic society, putting the conditions for security above the conditions for living in a free and democratic society. The PRISMS Project has questioned this trade-off relationship by organizing a series of reflexive studies and by organizing a pan-European survey in which EU citizens have been asked how they perceive situations in which both privacy and security are addressed on equal footing. The reflexive studies showed how the political discourse on privacy and security inevitably – at least so it seems – considers privacy infringements to be legitimized by referring to the security threats that present-day society faces. The framing is solid, and is hardly questioned (Huijboom and Bodea 2015). An analysis of technological practices shows, on the basis of various cases, how technological practices are framed in security jargon while privacy is minimized as a potential technological asset (Braun et al. 2015).

The survey focused on general attitudes of European citizens vis-à-vis the tradeoff model. The use of the terms ‘privacy’ and ‘security’ was avoided in the survey to prevent the a priori framing of these concepts as this often occurs in surveys.1 The results of the generic part of the survey have been reported earlier (Friedewald et al. 2015a). The results demonstrate that citizens do not consider security and privacy to be intrinsically linked. The results rather show that citizens simply want both: if no direct link is presupposed between privacy and security, citizens consider both values relevant for their well-being. They also consider the concepts that give rise to security different from the concepts that give rise to privacy, thereby questioning the existence of the trade-off.

In this chapter we will explore another element of the trade-off in greater detail. The survey used the so-called vignette methodology to concisely describe a number of situations in which both security and privacy issues play a role (again, without using the terms privacy and security in the description of the vignettes; see Appendix A for the vignette descriptions) (Hopkins and King 2010: 201–222). Respondents were subsequently asked in what sense they agreed with the situation, and whether they considered the situation to impact on fundamental rights. For some of the vignettes a number of alternative approaches were presented. These approaches either offered an alternative for the measure, which was described or alleviated parts of the measure.

In this chapter we will start with a concise presentation of the vignettes. We will then outline the research method for studying the vignettes, followed by a presentation of the overall results. Finally, two vignettes that reflect extreme responses will be presented in greater detail. The chapter will end with some conclusions from the interpretation of the results.

The vignettes – situations presented to European citizens

Having asked the respondents about their attitudes and concerns regarding more generic security and privacy features,2 the survey continued by presenting eight vignettes. A vignette represents a concise storyline that may help positioning the respondents in a specific situation. If done properly, a vignette refrains from explicating specific values (though the storyline itself can be used to discover how respondents value the represented situations). The PRISMS project team spent considerable time in drafting vignettes that covered different types of privacy, different sets of actors (public, public/private and private) and both online and physical contexts. A large set of hypotheses has been constructed that helped in mapping out the different contexts that should be covered by the vignettes. Many of these hypotheses deal with the orientation of independent variables (such as gender and age). In this chapter we will not start from the hypotheses as such, but we will present the results from these hypotheses whenever appropriate (see next sections).

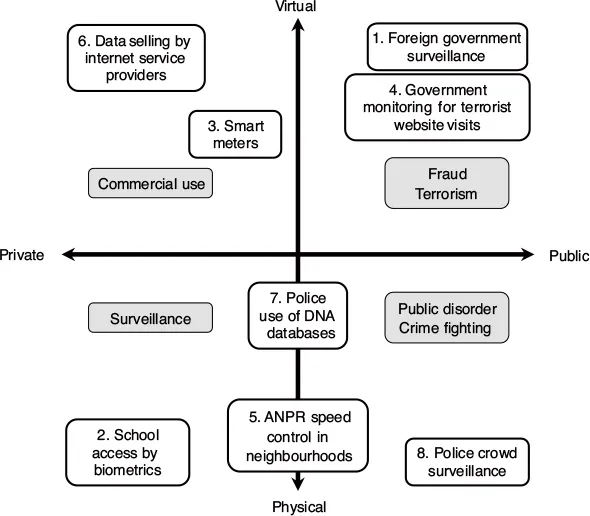

The vignettes were clustered around two axes. The first axis represented the variety of dominant actors in a vignette. This can be considered a relevant variable: we expected that public actors would receive more legitimacy for their actions than actors from the private sector in specific situations and for specific parts of the European population. Just to give an example: even though left-wing respondents generally will exhibit a higher resistance against the presence of the police in safeguarding specific events than right-wing respondents, one would still expect that left-wing respondents in general would accept the legitimacy of this actor. Similarly, one may expect that right-wing or more conservative respondents will accept a larger degree of influence by private actors than left-wing or more socialist/liberal oriented respondents. Trust in institutions is one of the variables we introduced to be able to make these distinctions as well as directly asking how respondents would position themselves on a political scale (see next section).3

The second axis differentiates between vignettes that are primarily situated in the online or virtual world and vignettes that are situated in the physical or real world. In many situations today one can observe an integration of online and offline activities.4 Still, the physical reality poses constraints different from the virtual reality. An almost trivial distinction is that within the physical reality actions do have a physical component. Monitoring speeding with cameras, for instance, means that physical objects – the cameras – are involved, which can be noticed. Of course, one can attempt to conceal the physical objects (such as hiding cameras behind trees or hiding them in boxes) but the physical dimensions of these cameras cannot be denied, nor can the physical dimensions of the objects they monitor (speeding cars) be denied.5 Legislation usually obliges the involved actor to indicate to the public that these cameras are in place and that people should know they are being observed.6 In virtual life, on the other hand, activities may go fully unnoticed. This can be so, because the actors involved use their skills to conceal their activities. It also can be the consequence of the limited ability of the observed to understand what is happening in the virtual world.7 This is a distinction between the virtual and the real world: in the real world, the first layer of observation is direct and requires no specific abilities on the side of the observed. Only when actors use specific strategies to conceal their activities, do additional skills and competences come into play.

Using these two axes enabled us to plot the eight vignettes in one figure (see Figure 1.1). The vignettes range from being set only in the virtual world to being set only in the real world and from having public actors engaged to having private actors engaged. They relate to:

Foreign government (NSA type) surveillance – a charity organization shown to be under surveillance.

Biometric access management system – using biometrics for access to a school.

Smart meters – using data from smart meters to offer additional services.

Monitoring visits on terrorist websites – a young person using the Internet looking at terrorist sites, potentially monitored by government.

ANPR speed control – using cameras in a neighbourhood to track speeding.

ISP data selling – Internet service providers selling data they collect on the Internet usage of their clients.

Police use of DNA databases – DNA data that has been provided for medical research but is used for other purposes as well.

Crowd surveillance – the police monitoring a crowd at a demonstration/ monitoring supporters and hooligans at a football match.

Figure 1.1 Matrix depicting the various vignettes along the axes virtual–physical and private–public

Source: Friedewald et al. (2016).

The survey – some methodological considerations

The composition of the sample

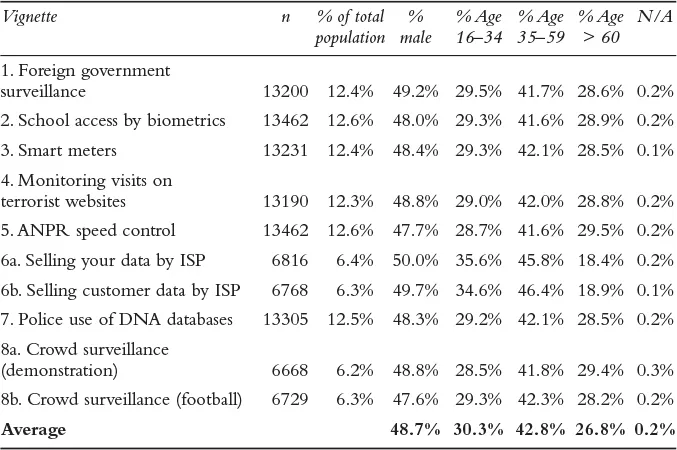

To study how European citizens perceive issues in which privacy and security play a role, we conducted a large-scale survey in all 27 EU countries. The data collection took place between February and June 2014. The survey company Ipsos MORI conducted around 1,000 telephone interviews in each EU Member State except Croatia (27,195 in total) using a representative sample (based on age, gender, work status and region) from each country (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Descriptive statistics of the sample

The vignettes that were constructed were refined through sixteen focus groups in eight representative EU countries. In this way, it was ensured that the vignettes would be understood uniformly in different languages and that they would not cause extreme reactions that would bias results. Each interviewee was presented with four randomly selected vignettes, resulting in approximately 13,500 responses for each vignette (500 per country). Appendix A provides descriptions of the vignettes.

Table 1.1 provides an overview of the sample for each vignette. On average, 48.7 percent of the population was male. Forty-three percent was in the 35–59 age. The population is evenly distributed across the vignettes, with the data selling and crowd surveillance vignettes equally split. The data selling vignette (6a/b) was received by a slightly younger population than the other vignettes.

Construction of variables

Dependent variable

For each vignette we constructed the same dependent variable, being the variable that indicates the relationship the respondents demonstrate in their responses to a specific vignette. This dependent variable is what we called the level of societal resistance (or acceptance, depending on the perspective one chooses) of the scenario presented in each vignette. For each vignette, respondents were asked to what extent, if at all, they thought the main actor in the vignette should or should not collect and process data in that specific scenario. Respondents were able to answer this question on a Likert-scale ranging from ‘definitely should’ (1) to ‘definitely should not’ (5). Consequently, a higher score means higher resistance and thus a lower societal acceptance of the vignette. The exact wording of the question is included in Appendix B.

Independent variables

Security concern was measured on a summated scale of perceived general security concern and perceived personal security concern. Respondents were asked how often they worried about a list of general and personal security indicators, with answer options ranging from ‘most days’ to ‘never’ (Friedewald et al. 2015b). The exact wording and indicators are included in Appendix B. To reduce the number of items and keep the information of all items, we conducted a factor analysis to see whether items could be combined in one construct. The factor loadings in the analysis showed that this was indeed possible on the European level, and thus a ‘high security concern’ scale was created by recoding the responses into low (0) and high (1) concern for security.

Attitudes towards privacy were measured by asking respondents to rate the importance of a list of indicators that measures the importance of keeping things private or privacy related actions. A factor analysis showed that items could be combined and the scale ‘high privacy concern’ was created accordingly, ranging from low (0) to high (1) concern for privacy.

To measure the perception of trust in institutions, the survey asked respondents to indicate for a number of institutions whether they do not trust this institution at all (0) or have complete trust in it (10). This question was recoded in a dummy variable with 0 = no trust at all and 1 = complete trust.8

Two alternative variables were taken into account in the analysis that measure attitudes to privacy and data protection practices in another way. The first is ‘experience with privacy invasion’. Respondents were asked whether they ever had the feeling that their privacy was invaded in seven different situations such as online, at a supermarket or at an airport. This was recoded into respondents who said they never had this feeling (0) and respondents who did experience this feeling (1). The second variable was privacy activism, which is how active respondents are when it comes to protecting the...