eBook - ePub

Mathematics of Keno and Lotteries

Mark Bollman

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 328 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Mathematics of Keno and Lotteries

Mark Bollman

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Mathematics of Keno and Lotteries is an elementary treatment of the mathematics, primarily probability and simple combinatorics, involved in lotteries and keno. Keno has a long history as a high-advantage, high-payoff casino game, and state lottery games such as Powerball are mathematically similar. MKL also considers such lottery games as passive tickets, daily number drawings, and specialized games offered around the world. In addition, there is a section on financial mathematics that explains the connection between lump-sum lottery prizes (as with Powerball) and their multi-year annuity options. So-called "winning systems" for keno and lotteries are examined mathematically and their flaws identified.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Mathematics of Keno and Lotteries als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Mathematics of Keno and Lotteries von Mark Bollman im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Mathematics & Games in Mathematics. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

Historical Background

1.1 History of Keno

Suppose that 20 monkeys are loose on 80 mountains, with no more than one monkey per mountain. If we send 10 soldiers out to catch the monkeys, and each soldier looks on only one mountain, how many monkeys do we expect them to catch?

That, in a nutshell, is keno. Over the course of time, the monkeys, mountains, and soldiers have been replaced by numbers, but the essence of modern keno is the same: The casino draws 20 numbers [monkeys] in the range 1–80 [mountains], either electronically or from a set of numbered ping-pong balls. Players select some numbers [soldiers]—not always 10 anymore—in the same range, and are paid based on how many of their numbers are among the casino’s drawn set of 20. In a nod to this fable, the language of keno still speaks of “catching” numbers, or how many numbers are “caught” by the player.

This story, of Chinese origin, is said to date back 1500 years, giving keno one of the longest histories of any casino game [91]. Legend holds that Chéung Léung (205–187 bce), of the Han Dynasty, devised an early ancestor of keno to raise money for the army and for the defense of the capital, at a time when funds were low [27]. This guessing game called for players to choose 8 Chinese characters from 120; the risk to the players was small and the rewards for a correct selection were great. Gamblers could buy a chance for 3 lí, and a winning ticket paid 10 taels, where 1 tael = 1000 lí, for payoff odds of 10,000 for 3—about 3333 for 1. The game was a success from the start; within a few decades, the operators’ wealth was said to be boundless [27].

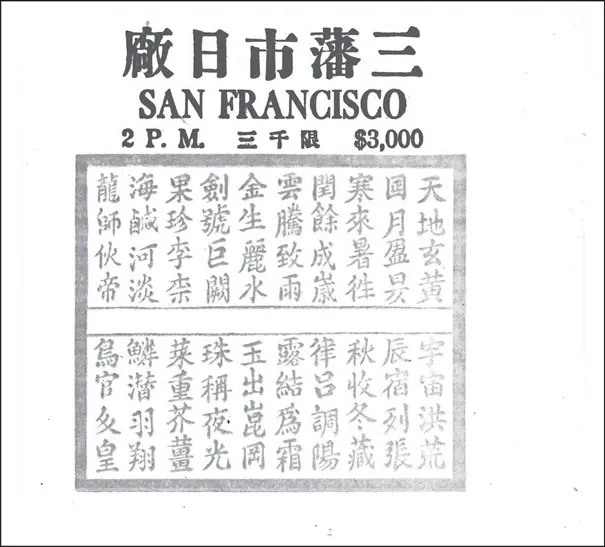

Pák kòp piú

Pák kòp piú or White Pigeon Ticket is an ancestor of keno that was brought to America by Chinese immigrants. The game derives its alternate name from the fact that in China, where lotteries were illegal in the 19th century, homing pigeons were frequently used to convey wagers and winnings between gamblers and game operators. Pák kòp piú tickets (Figure 1.1) bore 80 different Chinese characters rather than numbers, and drawings were typically conducted once daily, in the evening. The characters were the first 80 characters in the sixth-century book Ts’in Tsz’ Man, or the Thousand Character Classic. This book consists of a poem using exactly 1000 different Chinese characters, no two alike [27].

FIGURE 1.1: Pák kòp piú ticket.

The mechanics of a pák kòp piú drawing were very different from modern keno. The operator would, carefully and in full view of patrons, separate 80 pieces of paper, one bearing each character and rolled up against detection, into four bowls of 20 numbers each. A player would then be selected to choose one of the bowls, which was designated the set of winning characters. These steps were a confidence-building measure: if gamblers could see the mechanics of the drawing taking place, there was less reason to suspect that the game was rigged [27]. Another tamper-proof method of choosing the winning bowl was to number them from 1–4, then roll 3 standard dice, divide the sum by 4, and take the remainder as the number of the lucky bowl [92].

The primary wager at pák kòp piú called for players to choose 10 of the 80 characters. Its payoff table is shown in Table 1.1.

Payoffs in Table 1.1 are quoted as “for 1” rather than “to 1”, as is common in other casino games. The difference lies in how the player’s original wager is handled. A payoff of 2 for 1 includes the original wager as part of the 2-unit payoff, so the net profit is only 1 unit; if a game pays off a winning bet at 2 to 1, the player receives 3 units for every unit wagered: the original stake plus the prize of two units. This is standard practice when paying winners at keno and lotteries, where there is often a significant time lag between when the wager is placed and when the outcome is determined. It follows then that a bet paying off at “x for 1” is equivalent to a payoff of “(x − 1) to 1”.

TABLE 1.1: Pák kòp piú pay table, without commissions deducted [27]

Catch | Payoff (for 1) |

5 | 2 |

6 | 20 |

7 | 200 |

8 | 1000 |

9 | 1500 |

10 | 3000 |

Game operators charged a 5% commission on all winning bets, which reduced these payoffs. If the ticket was sold through an outside agent rather than directly by the operator, a further 10% was deducted from the payoff and paid to the agent.

Pák kòp piú spread to New Zealand and Australia with the entry of Chinese mine workers, where the name was soon Anglicized to pakapoo. Two pay tables for pakapoo are shown in Table 1.2. The wager was 6 pence (d); this was in pre-decimal British currency, with 12 pence per shilling (s) and 20 shillings to the pound (£).

TABLE 1.2: Pakapoo pay tables

Payoff (for 1) | ||

Catch | Game A [61] | Game B [13] |

5 | 1s | 0 |

6 | 8s 6d | 0 |

7 | £3 10s | £4 |

8 | £19 2s 6d | £20 |

9 | £35 | £40 |

10 | £70 | £80 |

As the game spread, the Chinese characters were replaced by numbers in order to allow non-Chinese to gamble without the need to understand the language. In the USA, pák kòp piú moved eastward, to Massachusetts first, then to Pennsylvania, Maine, Connecticut, and New York City [92]. The game found its strongest American market in Montana, when Chinese mining workers brought the game to their new country [34]. The Crown Cigar Store in Butte was home to what was called the Chinese lottery. Proprietors Joseph and Francis Lyden took possession of the game from Chinese agents in a deal with local officials.

The Chinese lottery provided for tickets containing anywhere from 9–20 spots; these tickets were processed by lottery officials by transforming them, in various ways, to collections of 10-spot tickets [16].

• A 9-spot ticket was interpreted as 71 different 10-spot tickets by combining the player’s 9 numbers with each of the 71 unmarked numbers to form a different 10-spot ticket. This ticket was sold for 71¢: 1¢ per virtual ticket. The pay table for a 1¢ ticket is shown in Table 1.3.

TABLE 1.3: Chinese lottery pay table: 1¢ ticket [16]

Catch | Payoff (for 1) |

5 | $.01875 |

6 | $.1875 |

7 | $1.875 |

8 | $9.375 |

9 | $18.75 |

10 | $37.50 |

• The 11-spot ticket was drawn as 11 different virtual 10-spot tickets; each one formed by striking out one of the player’s 11 numbers. This ticket was also offered starting at 1¢ per ticket, though it could be purchased for any number of cents per ticket.

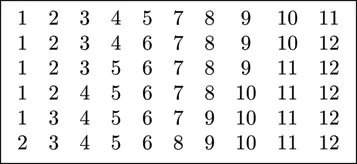

• A 12-spot ticket could be interpreted in several ways. The simplest led to 6 10-spot tickets. The player’s choices were numbered from 1–12, and a 6 × 10 array of numbers was formed by writing each number 5 times, proceeding vertically and filling the columns from left to right, as in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2: Resolution of a 12-spot Chinese lottery ticket into 6 10-spot tickets [16].

The rows of this table were then used to identify the numbers on each of the six tickets. This ticket could be had for 6¢.

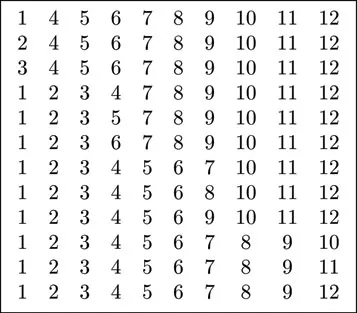

• An alternate approach to the 12-spot ticket involved grouping the 12 numbers into four groups of three each. Twelve different 10-spot tickets could then be constructed by choosing one number from each group and combining it with the 9 numbers in the other three groups to make 10. If the numbers were grouped {1,2,3}, {4,5,6}, {7,8,9}, and {10,11,12}, then these 12 tickets would be those shown as the rows in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3: 12 10-spot tickets derived from a single 12-spot ticket.

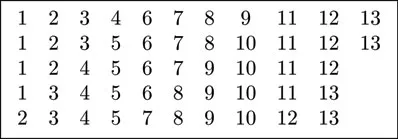

• 13-spot tickets were processed much like 12-spot tickets. The array of numbers, with each of the 13 choices repeated 4 times, is given in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4: Interpretation of a 13-spot Chinese lottery ticket as 3 10-spot and 2 11-spot tickets [16].

Once again, each row of this figure determines a ticket. This numbering scheme led to 25 tickets in all: the three 10-spot tickets, which were priced at 10¢ apiece, and 22 additional 1¢ 10-spot tickets arising from the two 11-spot tickets.

Similar schemes, all of which involved reducing a ticket down to some combination of 10-, 11-, or 12-spot tickets, were in common use for players wishing to mark 14–20 different numbers.

Keno evolved as it spread from Montana, eventually flourishing in Nevada after that state legalized gambling in 1931. Francis Lyden took the game from Montana to the Palace Club in Reno [34]. Initially, the game was called racehorse keno in Nevada in order to evade anti-lottery laws which still remain on the books, and the Chinese characters were replaced by the names of 80 fictional racehorses. Each horse was tagged with a number from 1–80, and by 1951, with a new tax on off-track betting introduced in Nevada, the horses’ names were dropped to avoid any possible connection with racing and players wagered on numbers chosen in that range [92, 141].

The game came to southern Nevada in 1939, with a game opening at the Las Vegas Club [156]. Joseph Lyden moved to Las Vegas in 1956, at which time he increased the drawing frequency from once a day to several times per hour, which became the standard frequency...