![]()

Chapter 1 Gang and Organized Crime History and Foundations

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter students should be able to do the following:

- Explore the first indicators of gangs in America.

- Identify key historical developments in the evolution of gangs.

- Consider some of the community issues present when gangs are involved.

- Discuss definitions of gangs and organized crime.

- Identify activities that are considered gang related.

- Examine group-focused theoretical approaches to the study of gangs.

- Understand ways that gangs serve as an alternative means of economic success.

Introduction

Gangs have been part of the American experience since the founding of this nation. They have been called street gangs, street corner gangs, inner-city gangs, urban gangs, suburban gangs, rural gangs, male gangs, female gangs, juvenile gangs, youth gangs, delinquent gangs, criminal gangs, outlaw gangs, biker gangs, drug gangs, and prison gangs. In a 1927 study, gang researcher Frederic M. Thrasher (2000) reported that gangs found among Chicago’s neighborhoods primarily comprised the following immigrant populations: Bohemians, Croatians, Germans, Greeks, Gypsies, Italians, Irish, Jews, Lithuanians, Mexicans, Poles, and Russians. In the decades since Thrasher’s study, we have discovered gangs in all 50 states, in many other countries, and on most continents, with only Antarctica as the exception. Gangs tend to appear in response to a social need. Needs in that category can be seen as protection against aggressors, providing social services, and generating revenue. Once the presence of the gang addresses the need, the gang may grow beyond the need. That would mean they could begin to become the aggressor, offer protection to others, or compete for revenue opportunities with legitimate organizations. Gangs seem to be drawn from every possible combination of demographic variables.

Organized crime, too, is a part of the culture of many societies. Organized crime groups often form from gangs, sometimes form independently, and are often less visible to police and the community than gangs, as they are often more advanced in their criminal organization and behavior. Organized crime groups, like gangs, tend to appear when the police and the politicians lack control. Organized crime groups are typically focused on profit.

This textbook was written to share information on gangs and organized crime groups in America. Readers of all types and experience levels should find value in the book, as the authors strive to share what they have learned about gangs in their respective professional and academic endeavors. You will see three common threads throughout the book. First, gangs and organized crime groups are made up of many individuals, hence their analysis and treatment should be focused more on the group than the individual. The second theme of the book is that the members of gangs and organized crime groups are typically adults, or led by adults. Finally, while at any given point in history there may be one predominant culture seen as being mostly engaged in gangs or organized crime, members of these organizations have come from many continents, countries, and cultures.

What you will not see is a focus on hate groups, domestic terrorists, or extremist groups. Hate groups advocate and practice hatred, hostility, or violence towards specific members of society. Domestic terrorist or extremist group members commit crimes that endanger human life intending to intimidate or coerce people, influence government policy, or change government conduct within the United States. Those groups are significantly different than the groups we identify here.

There is a lot of detail in some of the sections. We realize that there are many applications for this information, and did not want to limit the contents for one use while limiting the usefulness for another. For students, professors, and professional researchers, each chapter can serve as a stand-alone study topic. We recommend choosing the areas that are most relevant to the reader, either for the whole class or for a significant portion of it. For example, if you want to spend less time on a certain type of organized crime and more on investigation and prosecution of gang violence, simply using the selected chapters for study would serve that purpose. This recommendation would apply to a typical 15-week semester with midterm and final examinations.

For anyone working in one of the criminal justice fields, whether police, courts, corrections, or security, or another practitioner for whom gangs and organized crime groups are an interest, you should find the book useful as reference material, though hopefully

as a bit more of an interesting read than other reference material in your professional library. Should you encounter updated information on any of the topics in the book, please don’t hesitate to contact us by email –

[email protected].

The Early Gangs

Gangs were not always seen as criminal organizations. Gang violence was a part (often a condition) of life where the gang members lived (Sante, 1991). Gangs have been in existence in some form in Western society for about four centuries. Pearson found there were organized gangs like the Muns, Dead Boys, Blues, and Nickers in London in the 1600s. They terrorized their communities by breaking windows, assaulting the Watch (the police), and “rolling old ladies in barrels” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). Like more contemporary gangs, they wore colored ribbons to differentiate themselves and often fought each other for control of turf.

Gangs first emerged in the eastern cities of North America, which had conditions conducive to gang formation and growth, mostly created by the many waves of immigration and urban overcrowding (Sante, 1991). Haskins (1974) and Bonn (1984) reported that the makings of criminal gangs existing in America as early as 1760. Haskins noted that between 1660 and 1776, New York had evolved from a population of 1,000 with both an orphanage and a poorhouse and still had a group of “young, homeless boys” who were a nightly “source of trouble to respectable citizens” (Haskins, 1974, p. 16). Before the Revolutionary War, around 1764, Ebenezer Mackintosh led a gang-like group of men in Boston called the South Enders. Mackintosh was a shoemaker in his late twenties, and his gang looted the homes of several government officials in their protest of the Stamp Act of 1776, leading Mackintosh to become a powerful figure in the community (Haskins, 1974).

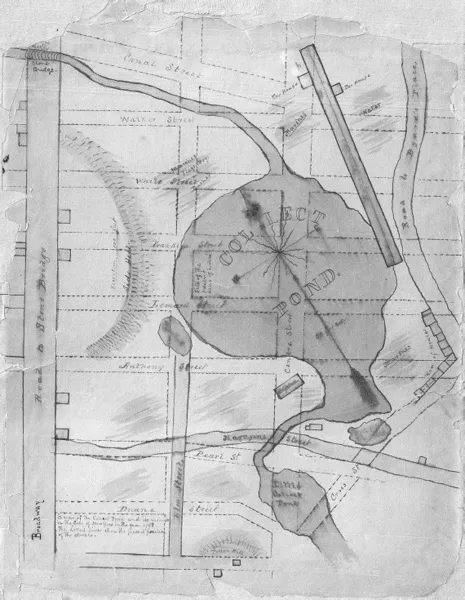

As with contemporary society, the problems with deviant youth were identified back then as either a lack of role models or insufficient supervision by authority. The earliest identifiable gangs in the U.S. came to existence shortly after the Revolutionary War (1775–1783; Sante, 1991). Haskins (1974) explained that following the Revolutionary War there was a time of lawlessness. When the British rulers were driven out, the police forces and other institutions were driven out as well. Combining that environment with the presence of idled young men who had left their country villages to seek a better life in the city, it may be easier to see why the resulting violence and mob activity occurred (Haskins, 1974). In New York, many of the gangs formed in the Five Points area, then on the outskirts of town. It was a wilderness surrounding a large lake referred to as the Collect.

Gangs of that period included the Bowery Boys, The Broadway Boys, and the Smith’s Vly gang, all of whom were white, and the Fly Boys and Long Bridge Boys, which were all-black gangs (Sante, 1991). Those gang members were nearly all employed in respectable trades like mechanics, carpenters, and butchers. Most of their gang activity consisted of arguing (and fighting) over the portion of territory each could claim as their own, much as contemporary neighborhood-based gangs do (Sante, 1991).

Figure 1.1

Map of the Collect Pond and Five Points, New York City. Public domain.

In the years that followed, America began receiving “scores of poverty-stricken immigrants” (Haskins, 1974, p. 22). A historical review of American gangs would suggest they emerged along both racial and ethnic lines. The early street gangs of New York and Chicago were almost exclusively made up of immigrants. Bonn described gangs as clearly having ethnic homogeneity in terms of their organization. “Irish gangs were the first to emerge,” followed by German, Jewish and Italian gangs (Bonn, 1984, pp. 333–334). According to Howell (2012), in both New York and Chicago, the earliest gangs formed in concert with the arrival of predominantly white European immigrants, particularly German, French, British, and Scandinavians, from 1783 to 1860.

The first criminal gang with a definite, acknowledged leadership, the Forty Thieves, formed around 1826 in the Five Points area of New York (Haskins, 1974). The name Five Points denoted the geographic location where five streets intersected, and a park named Paradise Square was situated at the hub. The second recorded gang, the Kerryonians, was named after the county in Ireland from which they came. Similar gangs with equally interesting names also formed in the Five Points area, including the Chichesters, Roach Guards, Plug Uglies (named after their large plug hats), Shirt Tails (distinguished by wearing their shirts outside their trousers), and Dead Rabbits (Haskins, 1974).

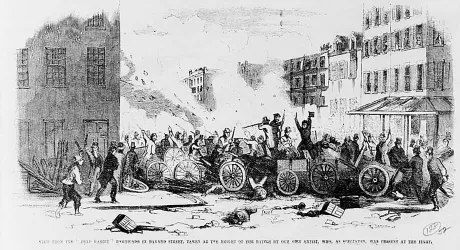

Figure 1.2

Early gangs. A fight between the Dead Rabbits and the Bowery Boys in New York City. From the newspaper article “Four Scenes From the Riot in the Sixth Ward” (1857). Public domain.

The second generation youth of immigrant groups were most susceptible to gang involvement. Asbury recorded crimes in Chicago in the late 1850s ranging from burglaries to holdups being committed by bands of men who were recently unemployed (1986). He identified one specific gang that was based out of the Limerick House and committed dozens of robberies. A thief known as John the Baptist led another gang of pickpockets (Asbury, 1986). He was apparently so named because of his attire and behavior, as he often left religious tracts behind.

New York–area gangs of the late 1850s included the Daybreak Boys, Buckaroos, Slaughter Housers, and the Border Gang (Sante, 1991). Many of the New York gangs hung out along the waterfront, so their crimes focused on people who lived and worked in that area. Muggings, murders, and robberies were their crimes of choice, and the area was considered so dangerous that the police avoided it unless there were at least six of them (Sante, 1991). In the late 1860s, German gangs began forming in New York. One gang, the Hell’s Kitchen Gang, terrorized the district for which they were named, committing robberies, assaults, and burglaries (Haskins, 1974).

Gangs in post–Civil War New York were snappy dressers, joining together for identity, wearing distinctive clothing (specifically headwear), and seeking publicity (Haskins, 1974). Haskins identified New York gangs of that era with names like the Stable Gang, the Molasses Gang, and the Silver Gang. Many came from poverty, and sought a group with which they could ally. Those gangs differed from previous gangs, as many of them were drug users (Haskins, 1974). When soldiers returned from the war addicted to the morphine they were given to ease the pain of their war wounds, they sought out more of the drug than they could legally obtain (Haskins, 1974). Gangs willingly provided a source for illicit drugs, and some gang members also became users. The most popular drug at the time was cocaine, which added a whole new dimension to gang activities.

The Whyos were the “most powerful downtown (New York) gang between the Civil War and the 1890s” (Sante, 1991, p. 214). The gang was made up of pickpockets, sneak thieves (stealing without detection or violence), and brothel owners. The gang members were very resourceful, offering their services to those in need in the form of a menu, listing the provision of two black eyes for $4, a leg or arm broken for $19, and a stabbing for $25 (Sante, 1991). The “big job” (presumably a murder) cost at least $100.

Perkins (1987) found that white street gangs had been documented in Chicago since the 1860s. Thrasher (1927) reported that most of the Chicago gang activity in the 1860s consisted of breaking fences and stealing cabbages from people’s gardens, as there was “not much else to take” (p. 4). Other groups, including Irish, Italians, Jews, and Poles, arrived from 1880 to 1920. Gangs of some type existed in Chicago as early as the 1880s, with groups like the Hickory Street gang spending their time reading, “play[ing] cards, study[ing], and drink[ing] their beer” (Thrasher, 2000, p. 4). Irish gangs like the Dukies and the Shielders influenced activity around the Chicago-area stockyards during that time, robbing men leaving work and terrorizing other immigrants (Howell, 2012).

The gangs fought constantly among themselves, but sometimes joined together to war with the black gangs. Many blacks (African Americans) had arrived from the southern states after the U.S. Civil War, most leaving to escape the oppressive Jim Crow laws and the life of the sharecropper. Cureton (2009) traced the origin of Chicago’s black street gangs to the segregated inner-city areas, beginning in the early 1900s. Cureton (2009) argued that the street gang (not the family or the church) was the most important social network organization for urban youth, even though it was the surest way to end up a felon, convict, or dead.

Elsewhere in the nation, criminal gangs that engaged in robbery were plentiful following the Civil War. Jesse and Frank James, for example, were motivated by their hatred of the Union to commit bank and stagecoach robberies. The brothers had fought on the Confederate side of the Civil War and, like many Southerners at the time, opposed the Union Army even after the war.

Early Juvenile Gangs

Historical accounts identify the institution of apprenticeships as a culprit, if not a contributor, to the prevalence of young, unsupervised men in the cities. The practice of apprenticeships matched a young male of 14 and above with an employer, who was presumed to be responsible for teaching the young boy a trade or employable skill. In those times, even young children were expected to contribute to the household income in many families (Pearson, 1983). Sadly, the system that supported the young teenage boys seeking apprenticeships appeared to be ineffective.

The apprentice system had been considered a problem since the early 1700s, as both the supervision of masters and the behavior of apprentices were being questioned. In the 1790s, as the increased supply of slave labor created an unnecessary surplus of apprentices, many an idled youngster was shuffled off to the orphanages. They often escaped and formed up with like-minded young men in “armies of homeless boys wandering about, stealing food, and sleeping in alleyways” (Haskins, 1974, p. 21). The apprentice system was an easy target for complaints regarding the increase in what was becoming known as “juvenile delinquency” (Pearson, 1983, p. 191). Pearson noted that some blamed it for causing the problem in the first place. Many of the young boys who were recruited as apprentices were described as idle and often violent, and were so numerous that they were a subculture of their own.

While previously there was a thriving business of child labor, either through apprenticeships or the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, the dynamics of the labor force changed when a concerted effort to stop child labor was started (Haskins, 1974). By the mid-1870s, over 100,000 children were working in New York factories, and when the reformation began, many of them were idled overnight. While many government efforts were implemented, at least 10,0...