![]()

Chapter 1

Leadership Needed to Promote Supervision, Professional Development, and Teacher Evaluation That Makes a Difference

In this Chapter …

- Supervision, professional development, and teacher evaluation are not linear, lockstep processes

- Leadership beliefs and practices to unify processes

- Coherence needed for instructional supervision, professional development, and teacher evaluation

- Accountability and high-stakes challenges for supervisors

Tool 1:Developing a Unif ed Vision for Supervision, Professional Development, and Teacher Evaluation

Introduction

Perhaps the most important work a supervisor does—regardless of title or position—is to work with teachers in ways that promote lifelong learning skills: inquiry, reflection, collaboration, and a dedication to professional growth and development. Educators today sense an urgency that stems not least from high-stakes expectations for students to perform well on standardized tests. In turn, these expectations focus attention on how teachers must improve their skills so that students can achieve more. Essentially, supervisors are teachers of teachers—adult professionals with learning needs as varied as those of the students in their classrooms.

Although there is debate about the value and emphasis placed on how well students do on standardized tests, there is little debate on the need for supervisors and others to foster the professional growth of teachers. For supervisors, this means that they must examine the fundamental ways of linking teacher support—supervision, professional development, and teacher evaluation. The accountability movement, although pushing for students to “bubble in” their knowledge on standardized tests, cannot reduce supervision and teacher evaluation to the results on a student’s standardized test score or a checklist filled out once a year. Race to the Top (RTT) is rooted in the belief that we need “great teachers and leaders” (Duncan, 2009, p. 9) and that teacher evaluation would play an integral part in measuring teacher effectiveness. With the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, teacher evaluation requirements are decoupled from federal regulations. There is now latitude to revisit the often thought punitive measures in teacher evaluation systems inextricably linked to becoming a Race to the Top state, receiving federal funds to implement such programs.

Perhaps we need to think about McGreal’s (1983) perspective that all supervisory roads lead to evaluation. Today, supervisory roads must intersect squarely with teacher growth and development by unifying purposes and expanding the roles that teachers play in the processes of supervision, evaluation, and professional development. For teachers to be the focal point at this intersection they must be more than bystanders; teachers must be the central actors assuming, alongside supervisors, the responsibility for growth. The challenge for supervisors is to extend learning opportunities for teachers through a unified approach to promote growth and development. They ignore this challenge at their peril.

Developing a vision for supervision, evaluation, and professional development is a reflective and iterative process. In cultures that are built on a foundation of collaboration, collegiality, and trust, supervisors are better able to promote the processes that support and actively engage adults in reflection and inquiry. There is urgency for supervisors to balance the types of support, the providers of these supports, and how these supports will be measured while simultaneously ensuring that teachers are growing as professionals capable and confident with their own learning.

Supervision, Professional Development, and Teacher Evaluation are not Linear, Lockstep Processes

Instructional supervision, clinical supervision, or any other form of support that aims to foster the professional growth of teachers cannot be reduced to a lockstep, linear process with a fixed beginning or end. The processes involved in supervision, professional development, teacher evaluation, and the like must be cyclical and ongoing. The clinical supervision model was originally designed to continue in cycles. Each cycle included a pre-observation conference, an extended classroom observation, and a post-observation conference. Each cycle served to inform future cycles and to identify the professional development needed to help teachers meet their learning goals. The intents of supervision (that is, its underlying purposes) are discussed in Chapter 2, and the processes of the clinical supervisory model are explored in Chapters 9 through 11.

Professional development (Chapter 4) and teacher evaluation (Chapter 3) must be linked to instructional supervision, embedded within and throughout the workday for teachers. What is needed is a model that connects the various forms of assistance available to teachers. However, no one model can ever be expected to fit the needs of every teacher and the contexts in which they work. There are ways to bridge supervision, professional development, evaluation, and other activities, such as peer coaching and mentoring. The real charge for prospective and practicing supervisors is to unify these efforts. One way to start is to scan a particular school building or organization. In addition to clinical supervision, what support systems are in place for teachers?

Extended Reflection

Identify the professional development and supervisory opportunities available to personnel in a school building. In the first column, list these opportunities. In the second column, describe how they are linked. See the following table as an example:

| Professional Development and Supervisory Opportunities | How These Opportunities Are Linked |

|

| Peer coaching | Numerous peer coaches serve as mentors, coaching teachers through direct classroom observation that includes both pre- and post-observation conferences. |

| Induction | The induction program includes mentoring, peer coaching, and study groups. |

| Study groups | Teachers form study groups and examine instructional issues; groups may read common materials; some teachers are involved in peer coaching; some teachers extend study group activities with teacher-directed action research. |

| Portfolio development | Action research teams are developing portfolios to track changes in practice. |

Teachers are the central actors in the learning process. In the final analysis, they are the ones who internally control what is (or is not) learned through school-wide efforts, such as peer coaching.

Prospective supervisors should seek a wide range of methods to extend the original model of clinical supervision. Examples include portfolio development, action research, peer coaching, and other original site-specific activities. All approaches need to be embedded in practice and linked as a unifying whole. A part of this unifying whole is professional development and the learning opportunities afforded to teachers. Because the original intents of the clinical supervision model included multiple cycles of conferencing and classroom observations, providing much information, namely data from the classroom observations and the insights gained by the teacher during extended discussions in pre- and post-observation conferences, it is logical to link ongoing professional development learning opportunities to supervisory efforts. Chapter 4 has a more purposeful discussion of job-embedded professional development and the linkages with instructional supervision and teacher evaluation.

Leadership Beliefs and Practices to Unify Processes

School leadership has substantial impact on student achievement (Honig, Copland, Rainey, Lorton, & Newton, 2010; MacNeil, Prater, & Busch, 2009). The work of leaders must continue to change swiftly and dramatically because “improving teaching quality and reducing the variability within that quality is a primary responsibility of school district leaders, building level leaders, and teachers” (Davis, 2013, p. 3). However, data from a 2009 Wallace Foundation study report that principals spend about 67 percent of their time focused on management functions (e.g., dealing with discipline) and 30 percent of their time focused on the instructional program (e.g., observing teachers, participating in professional development with teachers, providing feedback). Given the instructional leadership needed to support learning, these numbers seem to be flipped, with management duties trumping instruction and a focus on student learning and teacher development.

For schools to thrive, leaders today must engage in work that is much different than in the past. Principals, assistant principals, department chairs, or any others who supervise and evaluate teachers must be instructional leaders, capable of working with teachers in fundamentally different ways. Many of these changes have been motivated by the accountability movement and the prevalence of measurements—ones that measure student growth and ones that measure teacher effectiveness based in part on the results of student measures. Although there are inherent tensions in the role of the leader as supervisor, evaluator, and professional developer of teachers, high-stakes testing, sweeping curricular initiatives, and the proliferation of standards of practice have necessitated that principals understand and apply more complex skills in many different ways to support teachers who deliver the instructional program and the students who ultimately are the beneficiaries of these efforts. Beliefs influence practices.

Leadership Beliefs and Practices Pre- and Post-accountability

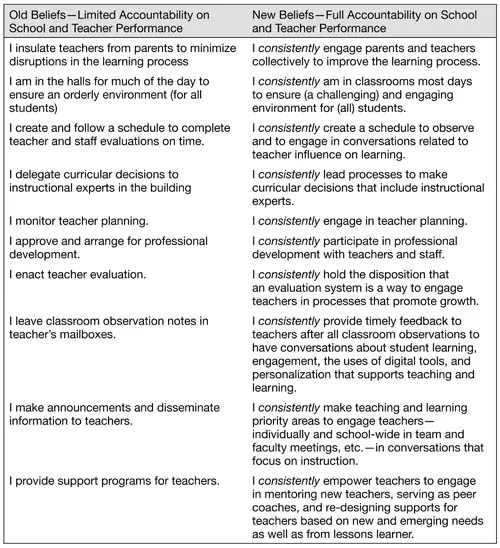

Leadership now is tied to the instructional program and the growth and development of the instructional staff—teachers, paraprofessionals, school counselors, and anyone else who influences students and the learning opportunities they need to be ready for the next steps in their lives. Hoy and Hoy (2013) are absolute in their beliefs that “good teaching matters, it is the sine qua non of schooling; in fact, good teaching is what instructional leadership is about: finding ways to improve teaching and learning” (p. 11). Figure 1.1 highlights “old” and “new” beliefs pre- and post-accountability and the work of the principal as an instructional leader (Zepeda, Jimenez, & Lanoue, 2015).

Figure 1.1 Old and New Beliefs Related to Accountability and the Work of the Principal

The National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2015) sets as foundation in the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders that school leaders “relentlessly develop and support teachers, create positive working conditions, construct appropriate organizational policies an...