Chapter 1

Introduction

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this chapter is to provide an understanding of:

- The functions and operation of financial systems.

- The nature of personal financial planning.

- The nature of investment risk.

People save and invest for various purposes: for holidays, home improvements, cars, deposits for house purchase, children’s education, old age, and general security. Some of these are shortterm objectives and others long term.The single biggest long-term objective is usually the provision of a retirement income. The time horizon of the investment will influence the nature of the investment. Savings for a holiday are unlikely to be put into a risky investment such as shares. Saving for a pension is unlikely to be in low return investments such as bank or building society accounts.

The largest investment item for many people is their pension fund. At an annuity rate of 8% per annum (p.a.), a pension of £20,000 a year requires a pension fund of £250,000.Whether a pension is being provided by an employer or being funded by the employee, a substantial sum of money needs to be accumulated. So successful investing is vital.

The need to invest for retirement is becoming increasingly important as governments progressively back away from promising adequate state pensions. In Europe and North America, as well as elsewhere in the world, the proportion of retired people in the population is rapidly increasing. This is often called the demographic time bomb. In the United Kingdom (UK), for children born in 1901, the average life expectancy was 45 for males and 49 for females (Harrison 2005). Those born in 2002 had average life expectancies of 76 for males and 81 for females. Life expectancy is steadily increasing, and with it the average period of life in retirement.The result is a rising ratio of pensioners to workers. It is often seen to be unrealistic to expect those of working age to pay the increasingly high taxes needed to pay good pensions to members of the retired population. One answer is to encourage people to provide for their own pensions by accumulating pension funds during their working lives (another approach is to raise the retirement age).

Table 1.1 Percentage of the population that is 65 or older

According to a World Bank publication (Palacios and Pallares-Miralles 2000) the percentages of the populations of the UK, Germany, and France over 60 in 2000 were 20.7%, 20.6%, and 20.2% respectively. The expected percentages for 2030 were 30.1%, 36.35%, and 30.0% respectively. According to the US Census Bureau (1999), in Western Europe (the members of the European Union as of 1999) the ratio of people of retirement age (65+) to those of working age (20–64) was about 0.15 in 1950. By 2000 it had nearly doubled to 0.29. It is projected to approximately double again, to about 0.64, by 2050.The ratio of pensioners to people of working age would have risen from about 1 to 6 in 1950, to around 4 to 6 in 2050. It is clearly unrealistic to expect those of working age to be able, and willing, to pay sufficient taxation to provide so many retirees with adequate pensions. Table 1.1 shows some Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) figures that illustrate the ageing populations in a number of countries (derived from OECD population pyramids).

There is also the issue of how to invest. Stock market investments, particularly shares, are seen by many people to be too risky. However, historically shares have massively outperformed other forms of investment such as bank deposits.The issue of relative risk needs to be seen in relation to an investor’s time horizon.The picture from a 40-year perspective is very different from that of a one-month perspective. Investments in shares can benefit from time diversification; over a long time span good periods can balance out bad periods. Also from a long-term perspective, the accumulated income from investments becomes more important in determining the final sum accumulated. For example £1,000 invested at 4% over 40 years will grow to £4,801, whereas at 8% it would grow to £21,725.The income receipts from stock market investments may be more stable than the interest receipts on bank or building society deposits.

According to the Barclays Capital Equity Gilt Study (1999; the study is updated annually on the Barclays Capital website), £100 invested in a balanced portfolio of UK shares in 1918 would have grown to nearly £420,000 by 1998 (with dividends, net of basic rate tax, being reinvested). An investment of £100 in Treasury bills over the same period would have grown to less than £2,500 (the Treasury bill rate of return is roughly equivalent to premium bank or building society deposits). These represent rates of return of approximately 11% p.a. and 4% p.a. respectively. When allowance is made for the effects of inflation on the purchasing power of money, the average rate of return from bank and building society deposits has not been far above zero.The message seems to be that the accumulation of wealth over long time periods, such as the periods typically required for the accumulation of pension funds, requires investments to be made in stock markets.

FUNCTIONS OF FINANCIAL SYSTEMS

A financial system can be looked upon as a combination of financial markets, institutions, and regulations that aim to perform a set of economic functions. Most of those functions have a direct bearing on investment decisions and behaviour.The functions might be regarded as the provision of means of:

- Settling payments.

- Investing surplus funds.

- Raising capital.

- Transferring funds from surplus units (savers) to deficit units (borrowers).

- Managing financial risk.

- Pooling resources.

- Dividing ownership.

- Producing information.

- Dealing with incentive problems.

- Settling payments. This refers to the mechanisms for making payments. Mechanisms include cash, cheques, credit cards, and so forth. This relates to investment only in so far as there needs to be a mechanism of paying for investments.

- Investing surplus funds. This is the investment process. Investors have varied needs and wishes concerning risk, return, liquidity, and other characteristics of investments. A financial system should provide a wide range of investment choices so that individuals can satisfy their investment objectives.

- Raising capital. Some people or organisations have expenditure that exceeds their income. They would need to raise capital by borrowing or selling shares. A financial system should provide suitable financial instruments for obtaining funds. Such instruments would include bank loans, various forms of bond, and various types of share.

- Transferring funds from surplus units to deficit units. This brings functions 2 and 3 together. Not only should there be suitable financial instruments for investors and those raising capital, but there should be markets or intermediaries for bringing them together. For example banks are intermediaries that transfer money from investors who deposit money to borrowers who receive loans. Stock markets transfer money from investors, who buy shares or bonds, to the firms that issue the shares and bonds.

- Managing financial risk. Most people or organisations that invest or raise funds face risks from price movements. For example an investor in shares will lose in the event of a fall in share prices. Financial systems should provide instruments for managing such risks. Risk management instruments include derivatives such as forwards, futures, swaps, and options. There are also other risks that need to be managed, such as default risk. Financial systems generate credit rating agencies that inform investors of the levels of such risks.

- Pooling resources. When businesses and governments borrow they want to raise large sums of money. Individuals normally have small sums to invest. By pooling the small sums of a large number of individuals, large sums are made available to businesses and governments. The pooling of large numbers of small amounts is carried out by intermediaries such as banks, pension funds, and unit trusts.

- Dividing ownership. When an investor buys shares in a company, the investor becomes part owner of the company. Share issuance is a means of dividing the ownership of a company among a large number of investors.The transfer of ownership to investors entails the transfer of risks as well as prospective profits.

- Producing information. The most common form of information produced by financial systems is information about prices. This would include prices of shares, bonds, and money (interest rates are prices of money). Information about prices allows investors to measure their wealth, and helps them to take decisions about how to allocate their wealth between different types of investment. Interest rates are likely to influence decisions about saving and borrowing.

- Dealing with incentive problems. Incentive problems include principal-agent, moral hazard, and adverse selection problems. It is in relation to such matters that regulation can be particularly important.

Principal-agent problems can arise when investors allow others to take decisions for them, or follow the advice of others. For example an investor may allow a financial adviser to choose investments.There is a risk that the adviser chooses the investments that pay the highest commission to the adviser, rather than the investments that are best for the investor.This would be a case of the adviser exploiting the situation of having more information than the investor. The investor is referred to as the principal, the adviser as the agent, and the inequality of information as asymmetric information.

The principal-agent situation can lead to moral hazard. Moral hazard can arise when the agent takes the decisions but the principal bears the risks arising from those decisions. For example a fund manager may make investments that are riskier than the investors would like.This could be possible as a result of the fund manager (the agent) having more information (asymmetric information) than the investor (the principal).

Adverse selection can be another consequence of asymmetric information. Consider the case of annuities. Annuities are incomes for life sold by insurance companies. In exchange for a lump sum the insurance company guarantees a monthly income for the rest of the life of the person buying the annuity. Individuals know more about their health and prospective lifespans than insurance companies can know (asymmetric information). People with short life expectancy are less likely to buy annuities than those who expect to live for a long time (adverse selection).Those who expect long lives stand to benefit most from annuities. If insurance companies price annuities according to average lifespans, they will lose money because people buying them will tend to have longer than average lives. Women tend to live longer than men. If annuities are priced to match average life expectancy (average of men and women together), women will buy annuities to a greater extent than men.

INVESTORS AND BORROWERS

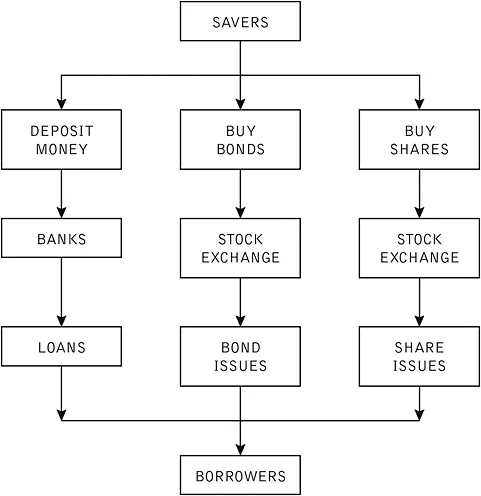

The financial system serves the function of transferring money from those who want to invest to those wishing to borrow (the term borrower is being used loosely here since firms that raise capital by issuing shares are, strictly speaking, not borrowing but selling equity in their enterprises).The cash flows are illustrated by Figure 1.1. Savers invest by depositing money in banks (or building societies), by buying bonds, or by buying shares.The borrowers may be individuals who obtain bank loans or mortgages, governments that sell bonds, or private companies that raise money by both of these means plus the sale of shares.The money passes from investors to borrowers through the intermediation of banks or stock exchanges.

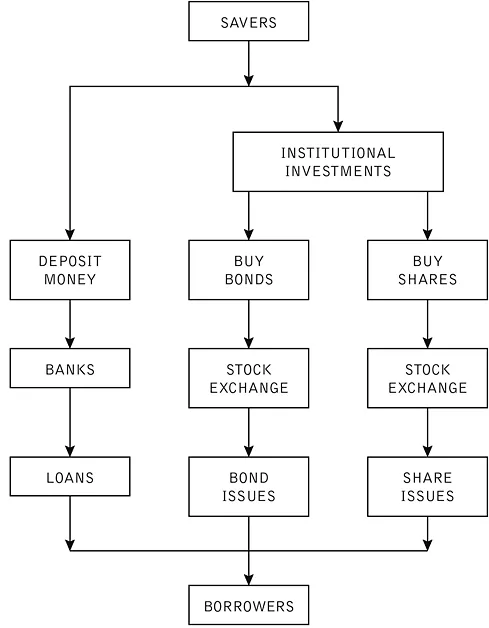

Most stock market investment by individuals is through the medium of institutional investments such as pension funds, insurance funds, unit trusts, and investment trusts.The financial system cash flows where stock market investment is carried out through institutional investments is illustrated by Figure 1.2.

PERSONAL FINANCIAL PLANNING

Personal financial planning is the process of planning one’s spending, financing, and investing so as to optimise one’s financial situation. A personal financial plan specifies one’s financial aims and objectives. It also describes the saving, financing, and investing that are used to achieve those goals.

A financial plan should contain personal finance decisions related to the following components:

- Budgeting.

- Managing Liquidity.

- Financing Large Purchases.

- Long-term Investing.

- Insurance.

Budgeting

The budgeting decision concerns the division of income between spending and saving. Saving will increase one’s assets and/or reduce one’s debts. If spending exceeds income (i.e. there is negative saving), assets will be reduced and/or liabilities increased. The excess of assets over liabilities is one’s net worth. Saving increases net worth (negative saving reduces it).

Some saving might be very short term, for example keeping some of this month’s salary to finance spending next month.Very short-term saving is part of the process of managing liquidity. Other saving is medium term: saving for a holiday, a car, or a deposit on a house are examples. Such saving is for the purpose of financing large purchases. Long-term saving can have an investment horizon of 40 years or more. The most important long-term saving for many people is saving for a pension to provide an income in retirement. Other purposes of long-term saving include the financing of children’s education, and building up an estate to pass to one’s heirs.

Long-term saving for a pension will feel much more important when the investor is 55 than when that investor is 25. However, early saving is far more productive than later saving. For example £1,000 invested for ten years at 8% p.a. will grow to £2,159, whereas the same sum invested at the same rate of return for 40 years will grow to £21,725.

Managing Liquidity

Liquidity is readily available cash, or other means of making purchases. Liquidity is needed for items such as day-to-day shopping and meeting unexpected expenses such as repair bills. Liquidity management involves decisions regarding how much money to hold in liquid form, and the precise forms in which the money is to be held. Generally the more liquid an asset is, the lower the return to be expected from it. The most liquid assets are banknotes and money in chequeable bank accounts. These assets provide little or no interest. Slightly less liquid assets, such as deposit accounts in banks or building societies, provide more interest but are slightly less accessible. It is normally inappropriate to hold all of one’s wealth in liquid form since assets that are less liquid (such as bonds and shares) generally offer...