available to an architect to set down a definitive and enforceable expression of standard and quality is by way of a properly drafted specification. If this is done, there is understanding and certainty all round. If it is not, there is often disagreement and disappointment.1

‘The objective,’ Hall emphasises, ‘must be certainty’.2

This recommendation reflects a long-held belief. In 1812, a Parliamentary Select Committee critiqued architect James Wyatt for ‘loose and inaccurate’ instructions at Somerset House and the Houses of Parliament and recommended that ‘precise arrangements should be made’ to guarantee the cost and quality of publicly funded works.3 A Select Committee in 1828 similarly sought ‘precise specification and careful superintendence’ and the explicit avoidance of ‘all deviations from the original plan.’4 Precise instructions in advance of construction are today still charged with guaranteeing certainty in any translation of an architectural intent into a constructed reality, as a more recent promise attributed to Building Information Modelling (BIM) promises:

It follows that the absence of conflict in the information given to the Contractors means that there should be no problems to resolve during construction.5

The specified aim of ‘no problems to resolve during construction’ will be familiar to many practising architects. The objective, it is recommended, must be certainty.

FIGURE 1.2 The project, as proposed: perspective.

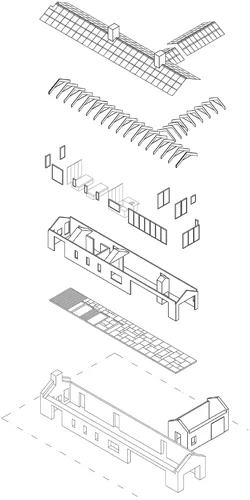

FIGURE 1.3 The project, as proposed: axonometric.

The wall, as proposed

The pursuit of certainty in our self-build in the Orkney Islands in northern Scotland had started simply enough. We had purchased the ruins of an 1851 flagstone longhouse and had paced off a plot of land for exchange with the farmer who owned the land. Sitting on a narrow stretch of land between Atlantic cliffs to the west and a wide sandy bay to the east, the remaining walls and collapsed roof sat on an east–west axis, the north side buried into the slight slope of the site, western gables thickened against prevailing westerly winds, windows facing south to capture the extremities of summer and winter solstice sun in a northern climate. The flagstone which made up the walls, roofing and flooring had been quarried from easily split layers from exposed beds on the coastline. An abundant material in an island landscape bereft of timber, these flagstones carried a geological, historical and cultural weight.

In Orkney, flagstone was used to construct Neolithic dwellings, burial chambers and stone circles. It was carved with decorative symbols by Neolithic and Viking populations and is captured in poetry describing its significance in Orkney as protective, enduring, symbolic. ‘Hearth stone, water niche, lintel’, twentieth-century Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown wrote of flagstone: ‘I can’t work wood’.6

The ruins of flagstone walls were a compelling starting point for our architectural intent. Trusting to the intuition and embedded knowledge of the nineteenth-century self-builders who had sited the longhouse in this exposed landscape, we proposed to retain the poetic, cultural, tectonic and protective flagstone shell. We planned to insert an insulated, dry, clean and easily assembled timber frame into the shell of the flagstone. This conceptual intent was to satisfy our amateur building skills, our need for contemporary comfort, our architectural idealisation of achieving a clearly defined, truthful, gap between the old and the new. As recently licensed architects we hoped, of course, to set out our architectural ideology with this small project. Concepts of truth and resonance lurked behind our insistence that the flagstone wall be retained. A gap between the ‘new’ and the ‘old’, as important conceptually as it was physically, offered tolerable contingency between the meticulously predictable standardisation of a contemporary timber frame and the unpredictability of an uneven, imprecisely hand-built flagstone wall, a condition which we struggled to capture with the detailed CAD drawings of our proposal.

The wall, as proposed, was to be 525.5mm thick, plus or minus assumed tolerances for the existing flagstone. It was to consist of: 12.5mm plasterboard, 12mm plywood, 150mm timber studs, 150mm sheep’s wool insulation, ‘Tyvek®’ building membrane, a 50mm cavity and existing 300–400mm flagstone walls, as the existing condition to which the precisely specified and drawn timber kit would be adapted. The concept was clear, predictable and meticulously drawn and costed, accommodating our predictions of contingency, risk and construction tolerance in both the preparation and assembly of materials. We were certain of our intent and of its translation into construction.

Of course, our project did not go as planned. Fifty years of exposure without a roof or collar ties had left the wall more unstable than first predicted by an initial site visit. Our drawings had predicted that we would demolish unstable areas of the wall, and insert a stabilising timber frame in the remaining structure. Instead, a recommendation from a locally experienced building inspector directed us towards the full demolition of the flagstone wall, rejecting the existing wall as unstable, unsalvageable. This was not an option we had previously considered. The removal of the existing wall was a significant unplanned deviation from our otherwise meticulously planned set of construction documents. More importantly, it fundamentally challenged the core architectural intent of our project, that of the bringing together of the poetic, historic, contextual in-situ flagstone wall with the precise order of a contemporary modular construction. To lose the flagstone wall would be to lose the architectural intent of the project.

Faced with this uncertainty, we sought to re-establish the certainty of our architectural intent. Perhaps, we argued to ourselves, a rebuilt flagstone wall could be in itself interpreted as truthful as a demonstration of the inevitability of deviation encountered in almost any architectural project. Reserving our guilt, we dismantled the flagstone wall and restacked the stones nearby in preparation for reuse. The timber frame was quickly completed on the grounds of the footprint of the removed wall by the end of a summer of construction, clad in plywood sheathing, and wrapped in a weatherproof membrane. We now faced the potential of leaving the membrane exposed over winter. Advised against this by the membrane manufacturer, as well as by our own growing knowledge of the site’s extreme exposure, we were again self-dir...