![]()

Part I: Overview of the cognitive linguistics enterprise

Introduction

Cognitive linguistics is a modern school of linguistic thought that originally emerged in the early 1970s out of dissatisfaction with formal approaches to language. Cognitive linguistics is also firmly rooted in the emergence of modern cognitive science in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in work relating to human categorisation, and in earlier traditions such as Gestalt psychology. Early research was dominated in the 1970s and 1980s by a relatively small number of scholars. By the early 1990s, there was a growing proliferation of research in this area, and of researchers who identified themselves as 'cognitive linguists'. In 1989/90, the International Cognitive Linguistics Society was established, together with the journal Cognitive Linguistics. In the words of the eminent cognitive linguist Ronald Langacker ([1991] 2002: xv), this 'marked the birth of cognitive linguistics as a broadly grounded, self conscious intellectual movement'.

Cognitive linguistics is described as a 'movement' or an 'enterprise' because it is not a specific theory. Instead, it is an approach that has adopted a common set of guiding principles, assumptions and perspectives which have led to a diverse range of complementary, overlapping (and sometimes competing) theories. For this reason, Part I of this book is concerned with providing a 'character sketch' of the most fundamental assumptions and commitments that characterise the enterprise as we see it.

In order to accomplish this, we map out the cognitive linguistics enterprise from a number of perspectives, beginning with the most general perspective and gradually focusing in on more specific issues and areas. The aim of Part I is to provide a number of distinct but complementary angles from which the nature and character of cognitive linguistics can be understood. We also draw comparisons with Generative Grammar along the way, in order to set the cognitive approach within a broader context and to identify how it departs from this other well known model of language.

In Chapter 1, we begin by looking at language in general and at linguistics, the scientific study of language. By answering the question 'What does it mean to know a language?' from the perspective of cognitive linguistics, we provide an introductory insight into the enterprise. The second chapter is more specific and explicitly examines the two commitments that guide research in cognitive linguistics: the 'Generalisation Commitment' and the 'Cognitive Commitment'. We also consider the notion of embodied cognition, and the philosophical doctrine of experiential realism, both of which are central to the enterprise. We also introduce the two main approaches to the study of language and the mind adopted by cognitive linguists: cognitive semantics and cognitive (approaches to) grammar, which serve as the focus for Part II and Part III of the book, respectively.

Chapter 3 addresses the issue of linguistic universals and cross-linguistic variation. By examining how cognitive linguists approach such issues, we begin to get a feel for how cognitive linguistics works in practice. We explore the idea of linguistic universals from typological, formal and cognitive perspectives, and look in detail at patterns of similarity and variation in human language, illustrating with an investigation of how language and language-users encode and conceptualise the domains of SPACE and TIME. Finally, we address the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis: the idea that language can influence non-linguistic thought, and examine the status of this idea from the perspective of cognitive linguistics.

In Chapter 4 we focus on the usage-based approach adopted by cognitive linguistic theories. In particular, we examine how representative usage-based theories attempt to explain knowledge of language, language change and child language acquisition. Finally, we explore how the emphasis on situated language use and context gives rise to new theories of human language that, for the first time, provide a significant challenge to formal theories of language.

![]()

1

What does it mean to know a language?

Cognitive linguists, like other linguists, study language for its own sake; they attempt to describe and account for its systematicity, its structure, the functions it serves and how these functions are realised by the language system. However, an important reason behind why cognitive linguists study language stems from the assumption that language reflects patterns of thought. Therefore, to study language from this perspective is to study patterns of conceptualisation. Language offers a window into cognitive function, providing insights into the nature, structure and organisation of thoughts and ideas. The most important way in which cognitive linguistics differs from other approaches to the study of language, then, is that language is assumed to reflect certain fundamental properties and design features of the human mind. As we will see throughout this book, this assumption has far-reaching implications for the scope, methodology and models developed within the cognitive linguistic enterprise. Not least, an important criterion for judging a model of language is whether the model is psychologically plausible.

Cognitive linguistics is a relatively new school of linguistics, and one of the most innovative and exciting approaches to the study of language and thought that has emerged within the modern field of interdisciplinary study known as cognitive science. In this chapter we will begin to get a feel for the issues and concerns of practising cognitive linguists. We will do so by attempting to answer the following question: what does it mean to know a language? The way we approach the question and the answer we come up with will reveal a lot about the approach, perspective and assumptions of cognitive linguists. Moreover, the view of language that we will finish with is quite different from the view suggested by other linguistic frameworks. As we will see throughout this book, particularly in the comparative chapters at the ends of Part II and Part III, the answer to the title of this chapter will provide a significant challenge to some of these approaches. The cognitive approach also offers exciting glimpses into hitherto hidden aspects of the human mind, human experience and, consequently, what it is to be human.

1.1 What is language for?

We take language for granted, yet we rely upon it throughout our lives in order to perform a range of functions. Imagine how you would accomplish all the things you might do, even in a single day, without language: buying an item in a shop, providing or requesting information, passing the time of day, expressing an opinion, declaring undying love, agreeing or disagreeing, signalling displeasure or happiness, arguing, insulting someone, and so on. Imagine how other forms of behaviour would be accomplished in the absence of language: rituals like marriage, business meetings, using the Internet, the telephone, and so forth. While we could conceivably accomplish some of these things without language (a marriage ceremony, perhaps?), it is less clear how, in the absence of telepathy, making a telephone call or sending an e-mail could be achieved.

In almost all the situations in which we find ourselves, language allows quick and effective expression, and provides a well developed means of encoding and transmitting complex and subtle ideas. In fact, these notions of encoding and transmitting turn out to be important, as they relate to two key functions associated with language, the symbolic function and the interactive function.

1.1.1 The symbolic function of language

One crucial function of language is to express thoughts and ideas. That is, language encodes and externalises our thoughts. The way language does this is by using symbols. Symbols are 'bits of language'. These might be meaningful subparts of words (for example, dis- as in distaste), whole words (for example, cat, run, tomorrow), or 'strings' of words (for example, He couldn't write a pop jingle let alone a whole musical). These symbols consist of forms, which may be spoken, written or signed, and meanings with which the forms are conventionally paired. In fact, a symbol is better referred to as a symbolic assembly, as it consists of two parts that are conventionally associated (Langacker 1987). In other words, this symbolic assembly is a form-meaning pairing.

A form can be a sound, as in [kæt], (Here, the speech sounds are represented by symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet.) A form might be the orthographic representation that we see on the written page: cat, or a signed gesture in a sign language. A meaning is the conventional ideational or semantic content associated with the symbol. A symbolic assembly of form and meaning is represented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 A symbolic assembly of form and meaning

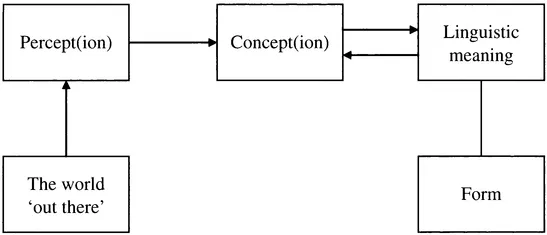

Figure 1.2 Levels of representation

It is important to make it clear that the image of the cat in Figure 1.1 is intended to represent not a particular referent in the world, but the idea of a cat. That is, the image represents the meaning conventionally paired with the form pronounced in English as [kæt]. The meaning associated with a linguistic symbol is linked to a particular mental representation termed a co...