![]()

PART ONE

Baby Boomers: Demographic and Theoretical Perspectives

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Demography of the Baby Boomers

David J. Eggebeen

Samuel Sturgeon

Pennsylvania State University

INTRODUCTION

It is appropriate that this book on the Baby Boomers at midlife includes a chapter on demographic characteristics, given that, at root, the Baby Boom was, and remains, a singular demographic event. Simply put, the Baby Boom was a fifteen-year splurge of births that emerged in the aftermath of World War II. It was a splurge because it represented a big reversal from long-term trends in fertility. A change, we might add, that was completely unexpected by those whose job it was to know these things (demographers). Ironically, despite this mistaken call, the Baby Boom phenomenon has probably done more than anything else to popularize demographic perspectives and approaches to understanding social change.

This chapter will begin with a brief review of this singular demographic event, its causes, and its early characteristics and consequences. The second part of this chapter will be a description of these Baby Boomers at midlife using demographic data drawn from various Current Population Surveys (CPS). Two key themes will drive the discussion: diversity and change. Baby Boomers are not a homogeneous bunch.1 We will explore variations among Baby Boomers by gender, race, and socioeconomic status (SES). We also will differentiate between the leading-edge Baby Boomers and those that followed. Specifically, we will compare the experiences of men and women, Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, college educated and non-college educated, Baby Boomers born in 1947–1949 (leading-edge), Baby Boomers born in 1953–1955 (intermediate), and those born on the trailing edge of the Baby Boom era (1960–1962). Our focus will be on work, marriage, living arrangements, and individual resources as these Baby Boomers enter and move through middle age. Finally, we will end this chapter with some speculations about the near future.

WHO ARE THE BABY BOOMERS?

In 1943 two prominent demographers, Warren Thompson and Pascal Whelpton, following accepted sociological theory, predicted that the U.S. population would not only stop growing, but would start to decline (Bouvier & De Vita, 1991). Less than five years later this prediction was in tatters. Starting in 1946, births began to surge. Just under a million more births tookplace in 1947 than had taken place in 1945. The number of births climbed each year, and, starting in 1954, annual births exceeded four million for the next eleven years (National Center for Health Statistics, 2003). Thompson and Whelpton predicted that the U.S. population would be 147 million in 1970. The actual count was 204 million. The difference between these numbers—47 million—is why those born between 1946 and 1964 are so fascinating. These excess births have been blamed for many of our nation’s problems—and many of its successes (Bouvier & De Vita, 1991). The profound cultural and economic dislocations of the past few decades are often traced back to the Baby Boomers (Easterlin, 1987; Macunovich, 2002).

What caused this Baby Boom? Demographers and others who study social change still are not in agreement on this. Until 1946, birth rates had been steadily declining since the turn of the century. It was clear to scholars why this was happening. Increased urbanization and modernization worked to transform American society away from its traditional and rural roots. American society and culture was increasingly characterized by individualism, rationalism, and a flexible, adaptable family structure that was in-tune with a modern, industrial-based economy. Smaller families were expected to become widespread. So why did America experience this sudden and unprecedented departure?

Two popular explanations for the Baby Boom are that the end of World War II brought home troops who made up for lost time, and that the Baby Boom represented a return to large families. Demographic facts do not support either pattern. Births did spike soon after the end of the war, along with marriages and divorces, clearly a response to demobilization, but this explains only the rise in births in the later years of the 1940s. Birth rates continued to rise through the 1950s, remaining high for nearly twenty years after 1945, suggesting other causes than merely the end of World War II were in play.

Neither was the Baby Boom a result of a return to traditional, large families. Work by Charles Westoff (1978) and others showed clearly that large families (four or more children) contributed little to the Baby Boom. What happened was that more individuals married, married sooner, had children sooner, had children tightly spaced, and more likely had two or three children (Bean, 1983; Bouvier & De Vita, 1991).

Why this change in marriage and childbearing? Scholars generally point to three sets of factors: demographic, economic, and social. Many view the booming post-war economy as a major factor. This historically unprecedented growth in housing, education, transportation and manufacturing created jobs—lots of jobs. Incomes grew at a rapid rate; prosperity was widespread (Levy, 1987). However, this extra income, as some have noted, was not expended on consumer goods or luxury items, but on extra children (Bouvier & De Vita, 1991). In a word, families “bought” a third child because they could afford them.

Sociocultural changes also contributed to the Baby Boom (Jones, 1980). The terrible dislocations of World War II—the massive mobilization of men into the armed forces, but also the restrictions on domestic life and widespread female labor force participation on the home front—created the conditions for a sharp increase in domesticity in the post-war years (Mintz & Kellogg, 1988). Not surprisingly, marriages increased, and they happened at earlier ages. Half of all women marrying for the first time in the early part of the baby-boom years were teenagers (Bouvier & De Vita, 1991). Given the early ages at marriage, the pace of childbearing increased. Having the two expected children at a younger age than previous cohorts, combined with the relative affluence of many couples, set up the conditions for what Charles Westoff (1978) called “a relaxation of contraceptive vigilance.” Thus, unwanted fertility, in the form of couples having a child beyond their stated preferences, was a major contributor to the Baby Boom.

Richard Easterlin (1987) has proposed the most comprehensive explanation of the baby-boom phenomenon. This theory is built on two key aspects: relative cohort size and relative income. Easterlin argues that the size of one’s birth cohort is a major influence on one’s life chances, because cohort size has a lot to say about the social and economic climate of society. The comparatively small birth cohorts of the 1930s benefited from less competition in schools and in the job market. Better pay and quicker promotions marked the work trajectories of the 1930s birth cohorts as they moved through adulthood. Because they were born during the Great Depression, their early lives tended to be marked by deprivation or economically modest lifestyles, leading, Easterlin argued, to relatively modest or simple tastes for consumer goods in adulthood. High income, combined with modest expectations for the good life meant many members of these 1930s cohorts developed an optimistic outlook on life—freeing them to not only marry, but to marry younger. Freeing them not only to have children, but to have more of them (Easterlin, 1987). Easterlin’s theory has proven useful to understand the marital and fertility behavior of the Depression-era birth cohorts and the subsequent marital and fertility behavior of the relatively large baby-boom cohorts (Easterlin, 1987; Macunovich, 2002). This theory, however, has not been without its critics, and its ability to account for the behavior of the “baby bust” birth cohorts (1970s) remains to be seen (Bean, 1983; Butz & Ward, 1979; Russell, 1982).

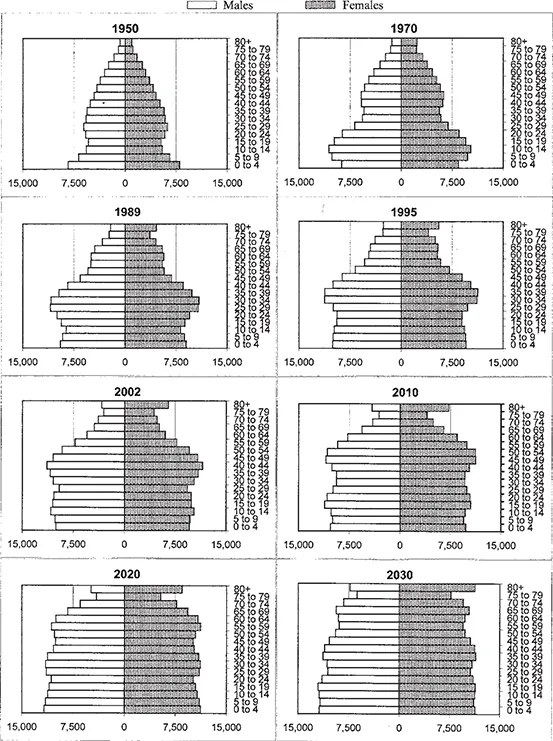

What have been the consequences of this massive surge in births? To begin to appreciate the context of the social changes typically traced to the baby-boom cohorts, it is helpful to see what has happened to the age structure of the American population since 1950. Figure. 1.1 displays a series of age pyramids for each decade from 1950 through 1980, 1989, 1995, and 2002, then projections forward to 2030. We have included 1989,1995, and 2002 because these years mark when the leading, intermediate, and trailing cohorts of the Baby Boom entered middle age by turning 40.

These graphs clearly show the distinctive size of the baby-boom cohort relative to the preceding and following cohorts. Comparing one panel to the next clearly shows the movement of the Baby Boomers through the age structure. In 1950, there were approximately 11 million 10- to 14- year-olds. The 1970 pyramid shows nearly double that number. From flooded maternity wards, to overcrowded classrooms, to the centrality of teenage culture, and the tight labor markets, the Baby Boomers have dominated social, economic, and cultural life in America, as many authors, scholars, and pundits have noted (cf. Jones, 1980; Macunovich, 2002; Russell, 2001).

The last three panels of Fig. 1.1 project what the age structure will look like over the next 30 years. Of course the size of the baby-boom cohorts at these three time points cannot be predicted with complete accuracy, given the necessity of making assumptions about immigration patterns and mortality trends. Nevertheless, these pyramids display, in broad strokes, what lies ahead. Over time, we see that the age pyramids will become more like rectangles, as the size of the elderly population will grow spectacularly relative to the other age groups. The implications of the aging of the baby-boom cohorts have received a significant amount of attention, little of it optimistic. Scholars and others warn of increased competition between young and old dependents for scarce public resources, looming financial crises surrounding the Social Security system, and concern over who, and at what cost, will meet the projected caregiving needs (cf. Alt, 1998; Hardy&Kruse, 1998; Pillemar & Suitor, 1998). Our focus in this chapter, however, is on these Baby Boomers at middle age.

Source: All reported populations and population projections are taken from the International Database.

FIG. 1.1. The movement of baby-boom cohorts through population agesex pyramids.

Baby Boomers at Middle Age

Our portrait of the Baby Boo...