eBook - ePub

Advances in Personality Assessment

Volume 7

Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher, Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 248 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Advances in Personality Assessment

Volume 7

Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher, Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This volume illustrates the diversity in assessment philosophy, theoretical orientation, and research methodology that is characteristic in the field of personality assessment. Topics range from anxiety about test taking and teaching science, to the emotional distress evoked by an environmental catastrophe.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Advances in Personality Assessment als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Advances in Personality Assessment von Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher, Charles D. Spielberger, James N. Butcher im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

Assessment of Sociopathic Tendencies

Sociopathy refers to a cluster of characteristics associated with the chronic occurrence of antisocial behaviors. Although this term has been and continues to be used interchangeably with psychopathy, there is a movement in psychiatry to subsume both terms under the diagnostic category, Antisocial Personality Disorder (DSM-II, American Psychiatric Association, 1968; DSM-III, American Psychiatric Association, 1980). However, given the frequency of current usage of sociopathy relative to the other synonymous concepts, this term is used throughout the chapter.

The major goal of this chapter is to report research findings concerned with the assessment of sociopathic tendencies. Specifically, the results from several years of research with a brief, self-report measure of sociopathy, the Sociopathy (SPY) Scale developed by Spielberger, Kling, and O’Hagen (1978), are described in detail. Before turning to these findings, however, the conceptualization of sociopathy that has guided this research effort is examined.

Concepts of Sociopathy

Interest in sociopathy predates by a number of years the establishment of psychology and psychiatry as formal disciplines. In 1801, Phillipe Pinel wrote about a mental disorder that he called mania sans delire, that is, a mental condition without disturbed reasoning or other common symptoms of insanity. Some 35 years later, James Prichard, an English physician, described a similar disorder that he labeled moral insanity. According to Prichard (1837), “the… moral and active principles of the mind are strangely prevented and depraved; the power of self-government is lost or greatly impaired, and the individual is… incapable … of conducting himself with decency and propriety in the business of life” (p. 157). And 130 years later, a strikingly similar description of sociopathic individuals was given in the DSM-II (1968):

Sociopathy is reserved for individuals who are basically unsocialized. They are incapable of significant loyalty to individuals, groups, or social values. They are grossly selfish, callous, irresponsible, impulsive, and unable to feel guilt or to learn from experience and punishment. Frustration tolerance is low. They tend to blame others and offer plausible rationalizations for their behavior. (p. 431)

The same theme can be found in the work of Hervey Cleckley. In the revised edition of his classic book, The Mask of Sanity, Cleckley (1976) described what he considered the distinguishing features of a sociopath. Among them were superficial charm, insincerity, lack of remorse or shame, poor judgment, pathological egocentrism, an incapacity for love, and general poverty in major affective reactions. Consistent with these descriptions, Hare (1970) proposed that a lack of empathy and a lack of concern with the welfare of others were the best indicators of sociopathy.

In contrast to conceptual definitions of sociopathy, the DSM-III (1980) listed a number of specific behaviors as criteria for the diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder. According to the DSM-III, this diagnosis is considered appropriate if, before the age of 15, a person has engaged in three or more of the following behaviors: truancy, expulsion from school, delinquency, two or more incidents of running away from home, persistent lying, sexual promiscuity, substance abuse, thievery, vandalism, school grades substantially below expectations, chronic violation of rules, and initiation of fights. Although these behavioral criteria may be useful in the diagnosis of the disorder, the DSM-III has been criticized for failing to capture the essence of the sociopathic disturbance (Davison & Neale, 1986; Rosenhan & Seligman, 1984). The DSM-III tells us what to look for, but seems to ignore why it occurs.

Because the research described in this chapter is concerned with understanding sociopathic phenomena rather than simply identifying sociopathic individuals, the material that follows has been influenced more by the conceptual definitions of Cleckley, Hare, and the DSM-II, than by the DSM-III. Given the common theme of antisocial behavior that runs through almost all views of sociopathy, it is not surprising that research in this area is typically based on samples drawn from mental or correctional institutions. The procedure most often used in these studies has been to employ some standard diagnostic tool (e.g., a clinical interview, behavioral checklist, or Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) profile; see Sutker, Archer, & Kilpatrick, 1981) to identify an institutionalized sample of sociopaths. Sociopaths are then compared to a nonsociopathic sample on variables such as physiological reactions to certain stimuli (e.g., Forth & Hare, 1986) or the ability to show avoidance learning (e.g., Schachter & Latané, 1964; Siegal, 1978).

The approach to the assessment of sociopathy in this chapter differs from prior research in several ways. First, the data collected on the SPY Scale were obtained primarily from college students rather than prisoners or mental patients. The use of nonclinical samples was predicted on the view that sociopathy is a general trait, or collection of traits (syndrome), which is manifested to a greater or lesser extent in the behavior of all people. Although sociopathic behaviors are antisocial, and therefore, undesirable from a societal point of view, they do not invariably get the actor into “trouble,” and may even sometimes produce considerable benefit for him or her. Thus, sociopathy is approached from the theoretical perspective of personality and social psychology rather than clinical and abnormal psychology, although it is clearly recognized that these approaches are not incompatible.

After a brief review of the development of the SPY Scale, data on its reliability, factor structure, and validity are presented. The validity of the SPY Scale was evaluated, first, by looking at patterns of intercorrelations between SPY scores and other personality scales developed primarily with nonclinical populations. Further information on validity was based on the ability of the SPY Scale to predict the occurrence of specific behaviors that, although not dangerous or clinically pathological, were clearly sociopathic in character.

Construction and Development of the SPY Scale

A full description of the rationale underlying the development of the SPY Scale and the procedures employed in the initial validation studies can be found in Spielberger et al. (1978). The major goal in constructing the SPY Scale was to develop “a measure of the degree to which an individual possessed the characteristics attributed by Cleckley to the psychopathic personality, and that were subsumed (in the DSM-II) under the category ‘Antisocial Personality’” (Spielberger et al., 1978, p. 36). The subjects used in the construction and initial validation of the SPY Scale were male offenders at a federal minimum security prison, which routinely administered the full MMPI as part of an intake test battery.

Prior research on sociopathy suggested that individuals with elevations on the MMPI Pd and Ma scales, and relatively low scores on all other MMPI scales, were likely to manifest sociopathic behavior (Gilberstadt & Duker, 1966). Based on these findings, inmates were selected for a “Sociopathic Criterion Group” if they met all of the following criteria:

- T-score on the Pd scale of 70 or above.

- T-score on the Ma scale of 65 or above.

- Total T-score on the two scales of 140 or greater.

- No T-score on any other MMPI scale of more than 65.

- No T-score greater than 70 on the MMPI validity scales.

Inmates with T-scores of 65 or below on all MMPI clinical and validity scales were assigned to a “Normal Contrast Group.” These criteria yielded 48 “sociopaths” and 47 persons in the “normal” group.

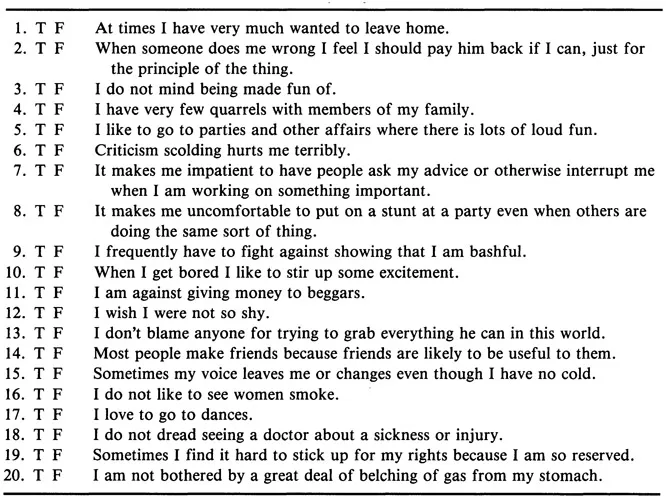

The sociopaths were randomly divided into two subgroups of equal size to permit cross-validation in item selection. The MMPI item responses of inmates in each sociopathic subgroup were then compared in separate analyses to the responses of the normal group. MMPI items that discriminated between the normals and both groups of sociopaths at the .10 level (combined probability of .01) were retained for the preliminary version of the SPY scale. Sociopaths’ responses to the retained items were then compared to the responses of 100 randomly selected inmates who were not part of the normal group. Twenty items that discriminated between these randomly selected inmates and the sociopaths comprised the final version of the SPY Scale, which is presented in Table 1.1.

Spielberger et al. (1978) reported findings from several studies that investigated the concurrent and construct validity of the SPY Scale. For example, inmates with SPY scores in the top 20% of the distribution scored higher than those in the lowest 20% on the Unsocialized Psychopathic scale of the Personal Opinion Study (Quay & Parsons, 1970), and had lower scores on the Socialization scale of the California Personality Inventory (Gough, 1960) and on Megargee’s (1970) Prison Adjustment Rating scales. Inmates with high SPY scores were also rated by counselors, parole supervisors, and prison psychologists as displaying significantly more sociopathic behavior than low scores on Craddick’s (1962) Checklist of Psychopathic Characteristics.

Reliability of the SPY Scale

The MMPI true-false response format was used in the original version of the SPY Scale. Although this binary format is acceptable for assigning subjects to “high” or “low” sociopathy groups, there often are problems in determining the factor structure and other psychometric characteristics of such scales (see Comrey, 1978; Nunnally, 1978). Therefore, most of the

TABLE 1.1 The Sociopathy Scale

data reported in this chapter were based on a version of the SPY Scale that employed a Likert-type five-choice response format.

The SPY Scale appears to have reasonably good temporal stability. Penner, Michael, and Brookmire (1979) found a 1 month test-retest reliability of .73. Graener (1980) obtained a test-retest reliability of .71 over the same time period. Data on the internal consistency of the SPY scale were obtained for two large samples comprised, respectively, of 399 and 881 undergraduates. In the first sample, the average inter-item correlation and Cronbach’s (1951) alpha coefficient were .04 and .47, respectively; in the second sample these values were .02 and .31.

According to Nunnally (1978), low interitem correlations and alpha coefficients may raise serious questions about the utility of the scale that yields them. In the case of the SPY Scale, however, the items were not written with the specific intent of tapping the same construct, nor were they selected from a larger item pool on the basis of item analyses that had revealed substantial covariation among them. The SPY Scale is comprised of items from various MMPI scales that significantly differentiated between sociopathic and nonsociopathic prisoners. Such empirically derived scales may often fail to display internal consistency (Briggs & Cheek, 1986) because they typically assess several relatively independent underlying dimensions.

It should also be noted that most theorists do not conceive of sociopathy as comprising a single psychosocial or personality dimension. Rather, sociopathy is conceptionalized as a cluster or constellation of characteristics (Sutker et al., 1981). Thus, the essential nature of sociopathy and the manner in which the SPY Scale items were selected both contributed to the heterogeneity of item content and the fact that the scale is not internally consistent.

Factor Structure of the SPY Scale

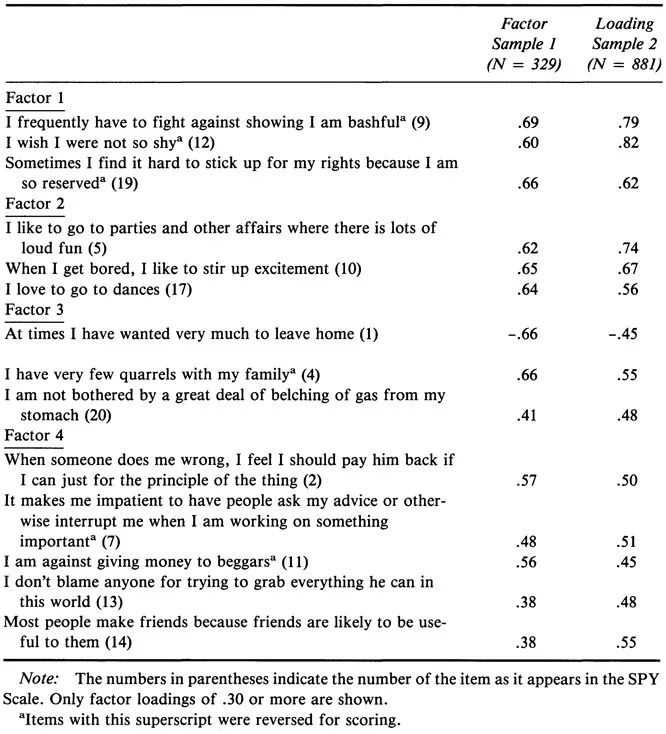

Given the heterogeneity of the SPY Scale items, a factor analysis was conducted to determine whether or not this empirically derived scale has any underlying theoretical coherence, or whether, as is often the case, “knowledge of the factor structure of the individual items (in an empirically derived scale) adds little to our understanding of the construct being measured” (Briggs & Cheek, 1986, p. 112; see also Gough, 1965). The item responses of the 399 undergraduates (the first sample previously mentioned) were subjected to principal components factor analyses with varimax rotation. In order to evaluate the replicability of the scale’s factor structure, the same analyses were performed on the responses of the 881 undergraduates in the second sample. The Scree test (Kim & Mueller, 1980) was used to determine the number of factors to be retained for rotation; in both samples, this test indicated that a four-factor solution provided the most meaningful description of the SPY Scale’s factor structure. This solution accounted for 35% of the total variance in the first sample and 40% of the variance in the second sample. Item loadings for the four factors which replicated across the two samples are reported in Table 1.2.

Of the 20 SPY Scale items, 14 had loadings of .30 or more on one of the four factors in both samples. The first factor, comprised of 3 items, appears to be concerned with whether or not the respondent is bashful, shy, and reserved. Because all 3 items are scored in the negative direction, sociopathic individuals do not see themselves as bashful, shy, or reserved. The content of these items suggests that this factor is tapping extraversión or social confidence.

The second factor is also comprised of 3 items, all scored in the “positive” direction; sociopathic individuals tend to agree with them. Item 10 seems to provide the best illustration of the construct being measured: “When I get bored, I like to stir up excitement.” Because this factor appears to reflect a desire for excitement and a low tolerance for boredom, it may be labeled as excitement or sensation seeking.

The third factor, also comprised of 3 items, had its strongest loadings on

TABLE 1.2 Factor Structure of the Sociopathy Scale

two items pertaining to the respondents’ family relationships. These items inquire about how the respondents get along with their family; sociopathic individuals respond positively to Item 1, which describes negative family interactions, and negatively to Item 4, which describes positive interactions. This factor can be called familial conflict.

The final factor, which consists of 5 items with loadings of .30 or more, is the most difficult to interpret. Let us first consider the 3 items scored in a positive direction (numbers 2, 13, and 14), which sociopathic subjects tend to endorse. The content of these items seems to reflect an egocentric, cynical view of the world and the respondent’s relationships with other people. But now consider the other two items with loadings on this factor. In terms of face validity, items 7 and 11 appear to be statements that sociopathic individuals would endorse. That is, one migh...