![]()

1

From Massive to Mass Customization and Design Democratization

BRANKO KOLAREVIC AND JOSÉ PINTO DUARTE

In this introductory chapter we address the current state of mass customization in architecture and design and the implicit promise of design democratization that has yet to find full social and cultural resonance. We discuss what mass(ive) customization means in architecture and the building industry and how it can be manifested in its most commoditized sector – suburban housing. We present parametric design and digital fabrication as the technological foundation for mass customization: through using parametric definition of the overall geometry and spatial layout, unique, customized houses could be designed. We use the term parametric design in a broad sense to include topological and dimensional variation, as well as variation of other shape attributes, such as material, color, and texture. Depending on the chosen systems for structure, enclosure, and partitions, their components could be fabricated with different degrees of automation by relying on digital fabrication and robotic assembly. We then examine what kind of mass customization is possible, useful, or desirable, and the conditions that could make design democratization a promising social and cultural construct. We explore whether design democratization, enabled by mass customization, is a viable proposition in the contemporary context, from technological, economical, cultural, and social perspectives.

Massive Customization

Various digital design and production technologies introduced in the late 1990s opened up unprecedented opportunities for architects to engage complexity and variability in formal articulation and the material realization of buildings.1 In the conceptual realm, digitally-driven, parametric design processes characterized by an inherent capacity for continuous transformation of three-dimensional forms gave rise to new architectonic possibilities. Digital fabrication technologies, such as computer numerically controlled (CNC) cutting and milling and three-dimensional (3D) printing, allowed the production and construction of uniquely shaped components that until then had been very difficult and expensive to produce. More importantly, the new digitally driven processes of design and fabrication offered a direct link from the designed geometry seen on the computer screen to the material production of components using CNC machines.

The consequence of these technological advances is that building projects today are not only born digitally, but they are also realized digitally through “file-to-factory” processes of CNC fabrication technologies. The processes of describing and constructing a design can be now more direct and more complex because the information can be extracted, exchanged, and utilized with far greater facility and speed. Thanks to parametric design and digital fabrication, it is now possible to mass-produce non-standard, highly differentiated products, from shoes and tableware to furniture and building components, and now even houses. Variety no longer compromises the efficiency and economy of production. Furthermore, parametric definitions of products’ geometry are made accessible via interactive websites to anyone, who could then design their own, unique versions of the product. (That at least was the optimistic vision; the reality is more nuanced, as discussed elsewhere in this book and later in this chapter.)

The digital technologies of design and production certainly left their mark on the architecture of the early twenty-first century. The sparse geometries of twentieth-century Modernism were in large part driven by Fordist paradigms of industrial manufacturing, imbuing the building production with the logics of standardization, prefabrication, and on-site installation. The rationalities of manufacturing dictated geometric simplicity over complexity and repetitive use of low-cost, mass-produced components. But these rigidities of production are no longer necessary, as digitally-controlled machinery can fabricate unique, variably shaped components at a cost that is no longer prohibitively expensive. Variety, in other words, no longer compromises the efficiency and economy of production.

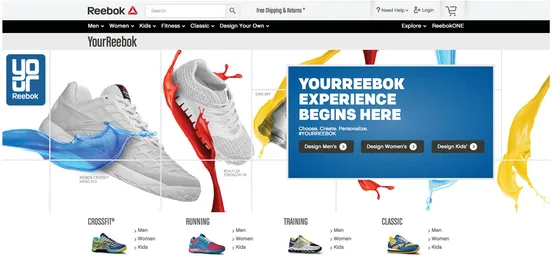

1.1 Today’s consumers have the option of designing their own, highly customized yet industrially produced products (Reebok, 2014).

The ability to mass-produce one-off, highly differentiated building components with the same facility as standardized parts introduced the notion of massive customization2 into building design and production – it is almost as easy and costeffective for a CNC milling machine to produce 1000 unique objects as it is to produce 1000 identical ones. In buildings, individual components could be customized to allow for optimal variance in response to differing local conditions, such as uniquely shaped and sized structural components that address different structural loads in the most optimal way, variable window shapes and sizes that correspond to differences in orientation and available views, and even functionally-graded material compositions of building parts in response to specific environmental conditions. The digitallydriven production processes introduced a different logic of seriality in architecture, one that is based on local variation and serial differentiation.

Toward Mass Customization

Massive customization of components in the building industry should not be confused with mass customization. Massive customization is a contemporary technological capacity that is afforded by advances in digital design and production technologies, as described earlier. Mass customization, on the other hand, is a contemporary business and marketing capacity that is aimed at meeting the unique needs of individual customers; it requires social and cultural conditioning so that customers – buyers of products, whether they are furniture, cars, or even houses – can demand and expect something unique, as opposed to a standard product that was mass-produced. In massive customization, we can randomly vary the characteristics of products; in mass customization, we need to link such variation to features of the context, be it physical features of the environment or social and individual features of product users, to obtain a product with higher performance.

Mass customization, defined by Joseph Pine as the mass production of individually customized goods and services, offered the promise of a tremendous increase in variety and customization without a corresponding increase in costs.3 Over the past two decades, almost every segment of the economy, from services and consumer products to industrial production, has been affected by mass customization.4 For example, today’s consumers could create their own unique, non-standard, industrially produced shoes (figure 1.1) and jackets, choosing materials, colors, and finishes as they please, at the same or marginally higher cost as the standard products made by the same manufacturer.

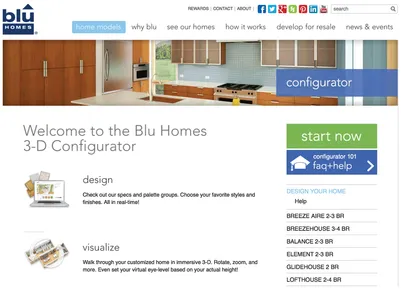

1.2 The “3D Configurator” by Blu Homes lets any visitor to the website choose and customize a selected house design.

1.3 Housebrand has conceived a complete design and delivery system (FAB House) based on modular house design that is highly customizable.

As we entered the twenty-first century, there was an expectation that the introduction of parametric design and digital fabrication into a variety of design fields would lead to a proliferation of websites that would enable everyone to interactively manipulate the shapes and forms of a wide range of products, whose geometry could be changed on the fly and, when fixed, digitally fabricated. The customized designs could be produced relatively quickly by the manufacturer and then shipped to the customer, or even better, inexpensively manufactured using locally available digital production facilities. The principal idea was that good design would become globally accessible, with production eventually taking place locally. Contrary to the expectations, that didn’t happen; the technology is there – parametric design, digital fabrication, integrated design and production processes, interactive websites – but what is missing is a broader cultural shift in society in how products are acquired. Turning customers into co-designers is an educational, cultural, and social challenge. It could be that the rather large majority of customers have no interest whatsoever in becoming designers.

1.4 House designs by Resolution: 4 Architecture can be customized by creating different relationships between pre-defined modules.

Customizing Houses

Websites by architects and/or builders currently exist that enable anyone to choose the house design they like, explore available options, and then customize it (within some carefully imposed limits). The “Design Your Own Home” website5 by Toll Brothers offers hundreds of stylistically very different house designs; each comes with several options that do not affect the overall geometry of the house, and the possibility to choose various material finishes. Blu Homes’ website6 features several different designs of prefabricated houses (figure 1.2), with various customization options; the process starts with “preliminary delivery assessment,” followed by “conceptual design” (online or in person) and “code and zoning research” as the final step. The “FAB” house (figure 1.3) by Housebrand from Calgary is a complete design and delivery system based on modular design7 that provides a considerable degree of freedom in how each house “shell” could be configured as a one-, two-, three-, or four-bedroom house, with considerable cost and time savings. The website by Resolution: 4 Architecture8 from New York offers “modern modular” homes (figure 1.4), with “predefined typologies … formed from a series of standard modules, minimizing cost of production and maximizing possible combinations available for the consumer.” They all offer ways to customize predefined house designs, but none of them offer interactive manipulation of the house’s overall geometry or its internal layout.

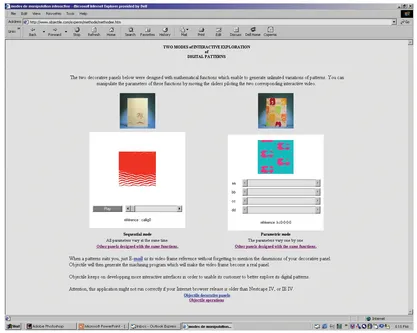

1.5 Bernard Cache, Objectiles, 1997. The online interface for designing objectiles, non-standard objects, features interactive manipulation of the parametrically defined geometry.

Mass customization is a particularly suitable production paradigm for the housing sector of the building industry, since houses (and buildings in general) are mostly one-off, highly customized products. It also offers a promise that a truly “customized” house – with a unique geometry, i.e. shape and form – could eventually become available to a broader segment of society. The technologies to deliver economically mass-produced, yet highly customized houses are there: parametric design, digital fabrication, interactive websites for design, visualization, evaluation, and estimating (and automatic generation of production and assembly data). The challenges for wider adoption of house design that can be interactively customized are not technological; as we argue below, they are largely social, i.e. cultural.

A mass-customizable house could be parametrically defined, interactively designed (via a website or an app), and digitally prefabricated, using file-to-factory processes. While this is technologically possible and economically attainable, it is nevertheless socially and culturally questionable. After all, how many of us have designed our own shoes or jackets? How many of us would dare design our own parametrically-variable car (if such an option were available)? How many of us would have the confidence that such a car would have good performance characteristics and be esthetically pleasing? Finally, how many of us are prepared to become designers instead of mere customers?

Democratizing Design

The implied “democratization” of design through mass customization raises additional questions such as the authorship of design and the functional and esthetic quality of products (shoes, tableware, furniture, houses) designed by non-designers.

Bernard Cache was one of the first designers to “democratize” design by making his parametrically defined furniture and paneling designs publicly accessible over the Internet in 1997. Cache’s objectiles, as he referred to his designs, were conceived as non-standard objects, procedurally calculated in modeling software and industrially produced using CNC machines. It was the modification of parameters of design that allowed the manufacture of different shapes in the same series, thus making the mass customization...