Introduction

The ultimate medical emergency, cardiopulmonary arrest, has been the focus of education and training of health care professions. Resuscitation teams were formed as early as the 1930s, however it was not until 1966 that the first cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines were published (Cooper et al. 2006b). Guidance on CPR continues to be updated (Resuscitation Council UK 2010), techniques in cardiopulmonary arrest are improving but results remains disappointing with survival rates to discharge for in-hospital arrests varying from 14.7 – 20.6% (Peberdy et al. 2008). Traditionally, much attention has been placed on after-arrest care, more recently however the emphasis has been shifting towards recognising those patients who are at risk of arrest or deterioration, with the aim of preventing the medical emergency occurring. Expert advice in the form of medical emergency teams (MET) and/or of outreach services is now a key feature in many acute trusts. Their aims are to prevent deterioration to cardiopulmonary arrest, averting the medical emergency.

Recognition of the problem

Patients who deteriorate and present as a medical emergency often require critical care. Whatever the cause or precipitating factor of a medical emergency, the physiological consequences for the patient are similar. Medical emergencies affect oxygen delivery to cells, tissues and organs. Oxygen is essential for glucose metabolism and aderosinetriphospate (ATP) production: without oxygen cellular and organ dysfunction, failure and death will inevitably ensue. Prompt responses are required to support failing organs until recovery or death and this often requires the support of critical care services.

A number of studies in the late 1990s highlighted problems with the recognition and management of the acutely unwell patient on adult wards. The evidence indicated that patients who deteriorate do not normally do so ‘out of the blue’ but have abnormal clinical parameters often some hours before the presentation of a medical emergency. Goldhill et al. (1999) looked over a 13-month period at patients admitted from the ward to the intensive care unit. This patient group had been in hospital for a minimum of 24 hours, and were at least 24 hours after surgery. The physiological variables at 0 – 6hrs, 6 –12hrs and 12– 24hr before admission were recorded. Goldhill et al. (1999) surmised from their data that abnormal respiratory rate, heart rate and adequacy of oxygenation were strong indicators that a patient was at risk of clinical deterioration. Many critically ill patients had been identified by the clinical staff in this study, monitoring had been increased and interventions such as oxygen therapy and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) had been commenced in some. Despite these efforts though, cardiopulmonary arrests were not averted. Schein et al. (1990) highlighted the importance of respiratory rate in their study, finding in the 64 arrests that occurred, the average respiratory rate prior to arrest was between 28 – 30 breaths per minute. Only 5% of these patients survived CPR to discharge. The conclusion drawn from these and other studies was that if the patients had been identified and treated appropriately earlier, it was likely that the arrests may have been prevented.

Early identification

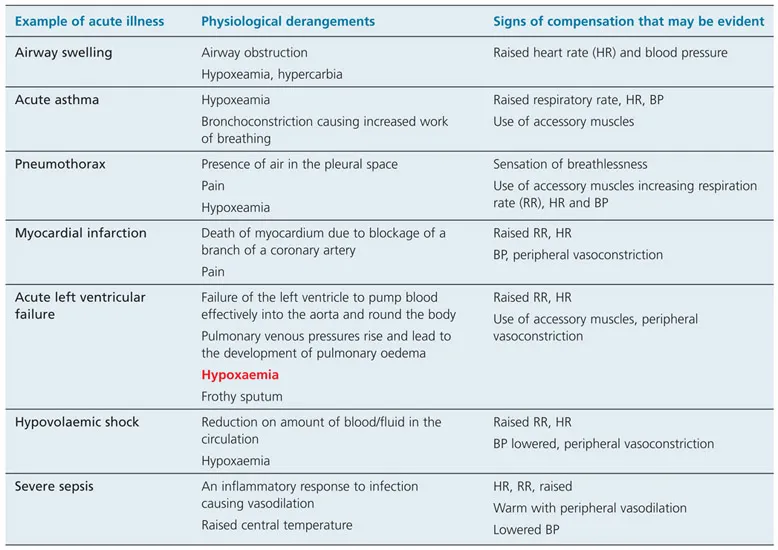

Although most people in hospital are unlikely to become seriously unwell, a significant number will require interventions in order to prevent or treat a medical emergency. Individuals move from experiencing minor physiological derangements, through a period of deterioration and more serious illness, which, if left undetected and untreated may progress to a life-threatening medical emergency, culminating in cardiopulmonary arrest. As people move along this continuum of wellness to the stage where death is imminent, they will be experiencing major physiological changes. The body will be attempting to restore homeostasis by the activation of compensatory mechanisms, such as increasing rate of breathing or heart rate. These compensatory mechanisms in themselves require additional energy, placing extra physiological demands on the individual. In the early stages of acute illness, these mechanisms may be sufficient to meet the extra demands, healing may occur and the problem resolve. However, if the underlying problem remains untreated, or is unresponsive to treatments, deterioration will continue. There may be a rapid progression of severity of illness resulting in cardiac arrest. Examples of acute illnesses that may or may deteriorate to a medical emergency are included in Table 1.1.

Understanding that signs of compensation may be indicative of acute illness with possible rapid deterioration should mean that if these clinical variables are recorded they can be addressed early in the continuum and the medical emergency averted. Unfortunately, this is not always the case, and when problems are recognised the appropriate treatment and management is not followed.

Table 1.1 Examples of acute illnesses that may lead to a medical emergency. Note how compensatory mechanisms of increased RR, HR and decreased adequacy of oxygenation are a feature of most of the above.

Suboptimal treatment

McQuillan et al.’s (1998) confidential enquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care identified problems with the management of patients in whom deterioration had been recognised. Some 100 consecutive adult emergency admissions between two intensive care units were prospectively reviewed. The management of the ward patients prior to their admission to intensive care was found to be suboptimal in over 50% of the acute emergency adult patients. Alarmingly, the majority of problems identified were with airway management, oxygen therapy, breathing and circulation, the very basics of acute care management. Patients who received poor-quality care before admission to the intensive therapy unit (ITU) were 20% more likely to die than those that received optimal care (McQuillan et al. 1998).

Adverse events in acute care are not only an issue for the UK, but are part of an international problem. An Australian retrospective review of 12 months of medical records of patients prior to development of medical emergencies revealed a failure of health care professionals to appreciate the urgency of clinical changes (Buist et al. 1999). Franklin and Matthew (1994) in their USA study reported a failure of communication between nurses and physicians, a failure of physicians to act appropriately, and failure of the ITU team to stabilise the patient prior to transfer to ITU. Another Australian project, the Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy (MERIT) study, randomised 23 hospitals to either use a medical emergency team, or to continue as usual (Merit Study Investigators 2005). This large study failed to demonstrate a direct effect of MET on unplanned emergency admissions to ITU or unexpected deaths: 50% of calls were made to the arrest team, without a cardiac arrest (non-MET group). This is in stark contrast to the UK where arrest teams are only summoned after the event. Interestingly, the cardiac arrest and unexpected death rate fell in both groups of hospitals during the study period.

The changing nature of acute care and acute care delivery

The profile of patients admitted to hospital has changed over the last few decades as the emphasis moves towards managing health care in the primary sector. The growing proportion of older people in the population combined with advances in management of many chronic illnesses has given rise to increasing number of admissions of older people, many of whom have several co-morbidities (Margereson 2010). This increase in the elderly popu lation contributes to greater seasonal variations in admissions, which culminated in the ‘winter bed crisis’ of 1998 – 9, when patients died due to lack of appropriate care facilities (Lipley 2000).

National initiatives in acute and critical care

The Audit Commission’s report in 1999, closely followed by the Department of Health (DH) publication Com prehensive Critical Care – A review of adult critical care services (DH 2000) recommended that patients should be classified according to their illness, and the appropriate care with necessary resources brought to them, expanding critical care provision and meeting seasonal surges in demand...