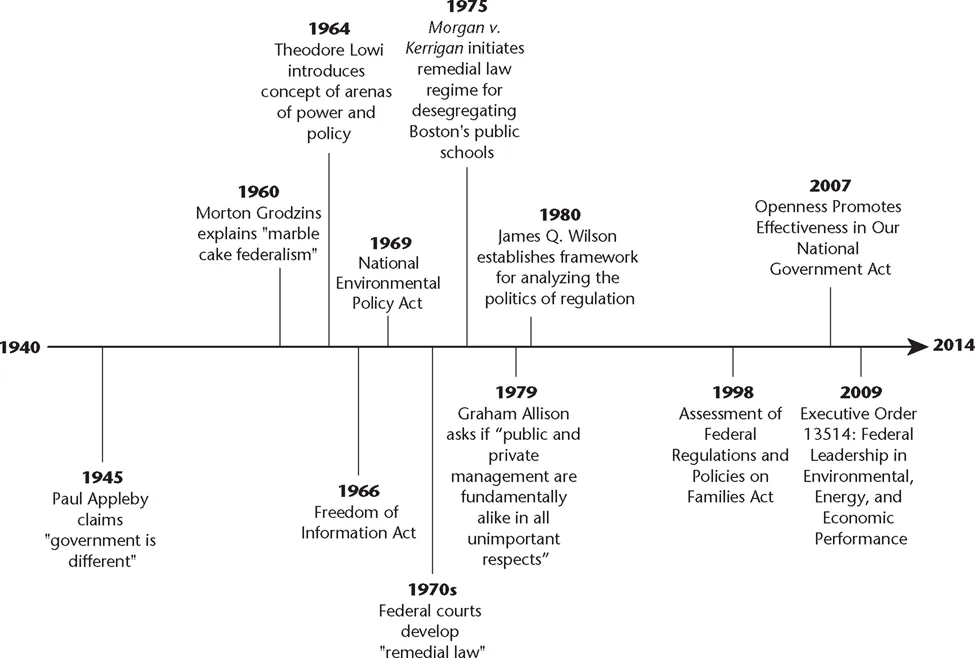

What is public about public administration? This question has been raised in the literature of public administration at least since 1945 when Paul Appleby claimed that “government is different” (Appleby 1945). In the late 1970s, taking Wallace Sayre's (1958) aphorism, “public and private management are fundamentally alike in all unimportant respects” as his lead, Graham Allison sought to provide a framework for “systematic investigation” of the “similarities and difference among public and private management” (Allison 1979). Since then a number of authors have compared public and private organizations with regard to red tape, research and demonstration, employee motivation, and other phenomena. Nevertheless, there is no consensus on how to answer what seems to be a simple question.

Perhaps this is because as a field of study, public administration has been without a dominant paradigm for almost all of the American Society for Public Administration's life, and certainly since the late 1940s. Lacking one, some researchers seek an answer to what makes public administration public by looking at the organizational level—how does the behavior of public and private organizations differ, if at all? (Bozeman 1987). Others focus on differences between public and private employees (Perry and Wise 1990). Still others examine the different environments in which both public and private organizations and employees operate. This body of research is ongoing, which suggests that it remains inconclusive and/or incomplete.

Yet there may be some consensus on what public administration is, regardless of whether it differs in important respects from private management, as Sayre implied. Since the 1980s, it has become commonplace that public administration combines management, politics, and law (Rosenbloom 1983; see also Meriam 1939). How it does so defines a great deal about the enterprise of public administration and the overall context in which it operates. This is not meant to suggest that the public and private sectors do not parallel each other in significant ways or that specific jobs in both sectors may be virtually identical. Note that Sayre did not explicitly state that public and private organizations are dissimilar in all important ways. The point is that by looking at management, politics, and law in the public sector we can observe a context that, as Appleby claimed, Sayre suggested, and others have researched, makes public administration different.

Management

What public managers do is another question without an immediate or straightforward answer (Ban 1995; Kaufman 1981; Morgan et al. 1996). They manage people, budgets, organizations, programs, stakeholders, information, communication, and more. Much depends on their level, political jurisdictions, organizations, and environments. The usual answer to what makes them public managers is that they overwhelmingly work in organizations that do not compete in output markets for their revenues. Even where they require user fees, such as those for obtaining a U.S. passport, they may act as monopolies. Further, although public managers may earn bonuses and salary raises, organizational profits (that is, excess revenues) are not ordinarily shared by managers, other employees, and/or stakeholders (including taxpayers). Nonprofit management is often taught in public administration programs rather than in business administration partly because under U.S. law, as with public agencies, their profits cannot be distributed to directors, officers, and members.

Whether being nonprofit is a sufficient answer as to what makes public managers public is a moot point. Perhaps Woodrow Wilson (1887) and John Rohr (1986) provided a better answer: they “run” the federal and state constitutions. Wilson did not expound on what he meant by “running a constitution.” Rohr was more concerned with the legitimacy of the administrative state than the likelihood that running a constitution will be problematic if the government working under it lacks the capacity effectively to implement policies, laws, international agreements, and judicial and other decisions. Implementation is what gives government the capacity to govern. Although legitimacy may contribute to capacity, history teaches that it is not a prerequisite except, possibly, in what may be a very long run.

Public managers at the federal and state levels run constitutions by coordinating the separation of powers. They are under the “joint custody” of, and subordinate to, three sets of “directors”: legislatures, chief executives, and courts (Rosenbloom 2001; Rourke 1993). Mission, authority, organizational structure, staff, and funding depend very heavily on legislatures. If legislatures do nothing, there is no administration, which is why W.F. Willoughby referred to Congress as the source of federal administration and asserted that it is “the possessor of all administrative authority” (1927, 11; 1934, 115, 157). Gubernatorial powers vary across the states and governors may have authority such as the line item veto that the president lacks. Regardless of these differences, the president and governors are expected to coordinate and manage government administration on a day-to-day basis. As the U.S. Constitution puts it, the president is expected to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” (Article 2, section 3; emphasis added).

When justiciable cases are before the courts, judges and justices apply the law to challenged administrative actions. If law is in the form of constitutional law, they not only apply it, but also, to put it uncomfortably, they make it. As Justice Lewis Powell once said, “constitutional law is what the courts say it is” (Owen v. City of Independence 1980, 669). Note that with the exception of the thirteenth amendment, banning slavery and involuntary servitude other than as punishment for crime, and what constitutional law regards as state action (that is, governmental action), the federal Constitution has no direct application to private relationships. Remedial law, as developed by the courts themselves in the last third of the twentieth century, enables federal and state judges to become deeply involved in the administrative operations of public schools, public housing, personnel, welfare, prisons, mental health systems, and other governmental activities (Chayes 1976; Cramton 1976; Rosenbloom, O’Leary, and Chanin 2010, chapter 7). It is more common for remedial law to involve state and local administration than federal activities. However, the way applicants for many federal positions are tested today reaches back to court decisions finding traditional merit system examinations legally defective for their lack of predictive validity and surfeit of negative disparate impact on the employment interests of minorities (see Ricci v. DeStefano 2009).

Public managers are legally required to act as instructed by chief executives and their appointees, legislatures, and courts. When all agree and are precise, the direction should be clear. When their directives are ambiguous, containing terms such as “feasible,” “public interest,” and “adequate,” or at odds with one another, the public administration and political science literature tells us coordination comes through bureaucratic politics. Public managers find themselves in the “Web of Politics,” as Aberbach and Rockman (2000) explain. The web has governments of strangers, issue networks, iron triangles, hollow cores, and its “lifeblood” may be political power (Long 1949). The rule of law should be followed, of course, but it is not always clear what it requires in terms of substance and pace. The choices Lipsky's street-level bureaucrats and O’Leary's guerrillas make and how upper-level managers, including political appointees, respond to them also affect coordination and implementation (Lipsky 1980; O’Leary 2006; Riccucci 1995; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003). So does agency “nonacquiescence,” which is not unusual, as when a federal agency bound by a ruling in one judicial circuit does not change its practices in the others, even though in all likelihood those processes are illegal or unconstitutional.

Subordination of public management to tripartite direction and supervision under the separation of powers can accommodate congressional authorization for a court to appoint an independent counsel with authority to exercise all the investigatory and prosecutorial powers of the Department of Justice while shielding the counsel from removal by the president and allowing dismissal only by the direct action of the attorney general for specified causes (Morrison v. Olson 1988). Coordination of the separation of powers goes to the very center of what Kerwin says is the most important thing agencies do, rulemaking (Kerwin 2003, xi). Congress delegates its legislative authority for agencies to make substantive (legislative) rules having the power of law. The president, through the Office of Management and Budget, exercises a considerable amount of control over the agencies’ rulemaking agendas and proposed and final rules. The latter are subject to congressional review and potential disapproval by joint resolution, subject to presidential veto and override. If litigation follows the enactment of substantive rules, which is common, the federal courts apply a “hard look” at their basis and purpose, and the connection between the two. Public managers have to manage rulemaking with the president's agenda, congressional committees and subcommittees, and judicial decisions in mind. Relying on the simplifying proposition that their primary obligation is to follow the president's direction is a copout. As Rohr emphasized, their oath is to support the Constitution (Article VI, section 3; Rohr 1978).

Public managers also coordinate federalism and intergovernmental relations. So many programs now involve two or three levels of government that coordinating them can be a full-time public management job. If coordination were not necessary, presumably there would be a much smaller literature on “cooperative federalism,” “new federalism,” and the Supreme Court and a return to “dual federalism.” Grodzin's classic description of a health officer's job not only reminds us that collaborative governance is not new, but also may still best convey the intermixing of administrative programs across federal, state, and local governments.

The sanitarian is appointed by the state under merit standards established by the federal government. His base salary comes jointly from state and federal funds, the county provides him with an office and office amenities and pays a portion of his expenses, and the largest city in the county also contributes to his salary and office by virtue of his appointment as city plumbing inspector. It is impossible from moment to moment to tell under which governmental hat the sanitarian operates. His work of inspecting the purity of food is carried out under federal standards; but he is enforcing state laws when inspecting commodities that have not been in interstate commerce; and . . . he also acts under state authority when inspecting milk coming into the county from producing areas across the state border. He is a federal officer when impounding impure drugs shipped from a neighboring state; a federal-state officer when distributing typhoid immunization serum; a state officer when enforcing standards of industrial hygiene; a state-local officer when inspecting the city's water supply; and (to complete the circle) a local officer when insisting that the city butchers adopt more hygienic methods of handling their garbage.

(Grodzins 1960, 265–266 as quoted in Grant and Nixon 1975, 37–38)

Competent sanitarians are required to coordinate and integrate all these health-related activities among the multiple jurisdictions involved. As an individual, a sanitarian may be quite adroit at doing so. However, supporting the sanitarian's work involves federal–state–local and local–local administrative coordination of budgeting, personnel administration, and allocation of office space, as well as the legal and policy aspects of implementing health regulations. Thinking in terms of bottom-up implementation theory, o...