eBook - ePub

How Architects Write

Tom Spector, Rebecca Damron

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 270 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

How Architects Write

Tom Spector, Rebecca Damron

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

How Architects Write shows you the interdependence of writing and design in both student and professional examples. This fully updated edition features more than 50 color images, a new chapter on online communication, and sections on critical reading, responding to requests for proposals, the design essay, storyboarding, and much more. It also includes resources for how to write history term papers, project descriptions, theses, proposals, research reports, specifications, field reports, client communications, post-occupancy evaluations, and emailed meeting agendas, so that you can navigate your career from school to professional practice.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist How Architects Write als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu How Architects Write von Tom Spector, Rebecca Damron im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Architecture & Architecture générale. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

one

HOW (AND WHY) ARCHITECTS WRITE

Now if it were asked: “Do you have the thought before finding the expression?” what would one have to reply? And what, to the question: “What did the thought consist in, as it existed before its expression?”1

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, philosopher

Architects often finish their sentences with a sketch.2

—Peter Medway, applied linguist

THE NEED FOR CLEAR WRITING

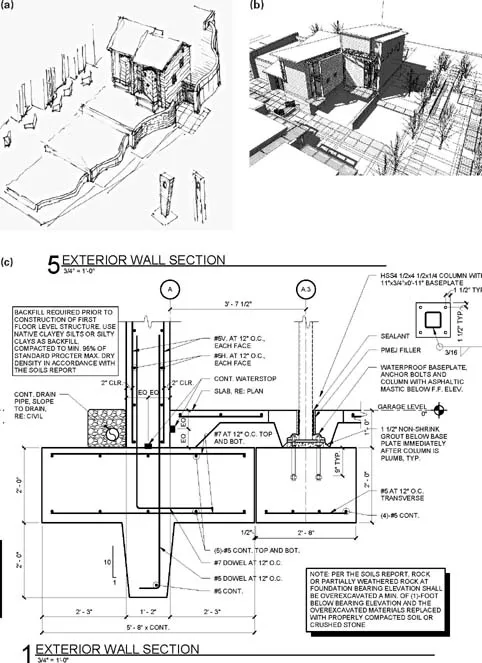

Clarity. If the objectives of this handbook could be boiled down to a single watchword, this would be it. The objective of writing clearly has so many dimensions—clarity of intent, clarity of expression, clarity of audience—that it can seem an overwhelming task at first. Fortunately, the task becomes less formidable when broken down into its four constituent parts (Figure 1.1): Good writers have sufficient command of their subject matter to convey confidence that they know what they are talking about. Their use of language is both clear and appropriate—they understand the rhetorical standards expected of them. They have a firm grasp on their writing process— not only mastery of the mechanics, grammar, and self-editing emphasized in freshman composition, but also of the steps required to, for example, organize their observations into reports. And they have clarified the expectations of their audience; that is to say, they understand the demands of the genre in which they are writing.

FIGURE 1.1 Writing’s four knowledge types: Writing Process Knowledge, Subject Matter Knowledge, Genre Knowledge and Rhetorical Knowledge

Writing Process Knowledge

Field notes, Feb. 22:

Steel erected to 45th floor

Electrical service entry discussed

Membrane roof installed on building 1

Curtainwall mock-up panel reviewed

Retaining wall stabilized

Elevator shaft wall #2 corrected

Prefabricated steel stairs ordered

Subject Matter Knowledge

Building: Hemispheric

Location: City of Arts and Sciences, Valencia, Spain

Architect: Santiago Calatrava

Date: 1998

Genre Knowledge

Evolution of High-Tech:

1.Early Milestones

a.Pompidou Center

b.James Stirling’s buildings in the UK

2.High-Tech goes mainstream

a.Norman Foster

Rhetorical Knowledge

Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin seeks to convey emotions of horror and moral outrage to the Holocaust in a museum experience. …

By mastering the elements of clear architectural writing— gaining command over the subject matter, employing appropriate rhetorical standards, establishing efficient processes, and understanding the demands of the different writing genres—students and practitioners will not only become better writers but will also make themselves better architects.

When the role of writing in architectural production was used primarily to explain a design that was already conceived visually, then the written word could be relegated to an ornamental role at the tail-end of a linear process.

Writing happened after all the really interesting work was done. But this conception is long out of date. Writing doesn’t just record what has already been done; it is part of the doing. What linguist Peter Medway discovered by observing both architectural practitioners and students was the fluidity with which architects must move between the graphic, oral, and written modes when developing and communicating design intent. This is the observation his quote at the beginning of the chapter is meant to convey. After observing architects at work in a number of different situations, he offers, “We are surprised and impressed by the linguistic virtuosity called for in the job.”3 Yes, sentences do end in sketches, but by the same token, sketches are illuminated by sentences. The design moves forward, not linearly, but iteratively as the designer gropes toward a desired future state of affairs. It gains authority as the mind incorporates information from a variety of sources. If design is allowed to be about more than the creation of geometric form, then a fluid conception that places design at the center of an activity informed by graphic, oral, and written modes is a more adequate representation.

If the linear conception of writing’s role in architecture was ever adequate, it certainly is not now. Both the increasingly collaborative environment of the construction economy, as well as technological advances in the design process, have placed a premium on architects’ ability to write to be effective on the job. Whereas at one time, architects might have conceived of themselves as visual artists handing off their designs for others to figure out how to build, today they are more likely to be at the center of an integrated team needing someone to organize its intense communication needs. These days, the value of one’s investments may fade, but emails are forever. Litigation—and preventing it—is heavily dependent on crisp, clear writing. However, it is important to remember that effective writing is not only business-oriented. No one achieves stature in the profession without at least one monograph explaining the firm’s design thinking. Press and criticism are as important as ever for building a critical reputation. Meanwhile, the explosion of information that can now be brought to bear on a building design means that someone must be able to manage and organize it, and the logical center of the design process resides with the persons charged with bringing the diverse sources of information together. To exploit the opportunities that the information age presents, architects must be able to write well, edit, and integrate the information generated by others into a coherent whole. The concept of the architect as Master Builder is disappearing, transforming into that of the architect as Master of Information. This new role is not a demotion, but it does signify a shift in how the world is pressing architects to think about design. In this emerging model, the design itself is usefully understood as either existing suspended at the center of a web of diverse information, or else as being the sum of all the information that comes to bear on it. Architectural form emerges out of—and becomes part of—the sea of relevant information, which includes the written word. Taken together, these developments make the need for achieving clarity in one’s writing all the more urgent, and central.

FIGURE 1.2 Writing’s Role in the Linear View: A design is conceived in models, drawings, and sketches; It is presented with advanced graphics and oral explanation; Instructions are communicated via 2D graphics and writing.

FOUR TYPES OF WRITING KNOWLEDGE: SUBJECT MATTER KNOWLEDGE, RHETORICAL KNOWLEDGE, PROCESS KNOWLEDGE, AND GENRE KNOWLEDGE

Think of the four aspects of clear writing as four different types of knowledge. Where and how are they transmitted? As it turns out, the majority must come from within one’s chosen discipline and cannot be subcontracted out to the English department with any expectation of success. Most of the work students do to improve their writing will necessarily come from within the architecture school curriculum. This is why the chapters in this book are organized around the typical writing tasks encountered as one progresses through school.

Subject Matter Knowledge

It is easy to see how one would be unable to think, much less write, perceptively within the field of architecture in the absence of such discipline-specific subject matter knowledge as architecture history, construction technology, and contractual relationships. By analyzing a fifth-year undergraduate student’s architectural design thesis, Medway saw the process of a student’s move into “architectural thinking” through a trajectory that included alternations of drawing and writing, a process that resulted in writing functioning as a design tool.4 In doing so, he demonstrated that students can never fully compensate for a spotty architecture vocabulary with, say, formal virtuosity because subject matter knowledge is so fundamental. Much of the writing done in architecture school is to demonstrate that one has assimilated and can synthesize subject matter information into one’s observations (Chapters 2 and 6) and one’s understanding of history (Chapters 3 and 8, especially).

FIGURE 1.3 Subject Matter Knowledge.

Rhetorical Knowledge

Some rhetorical knowledge does apply across disciplines, but only the most basic rhetorical elements of argumentation and logic can be effectively installed by outsiders. To see why this is so, consider Medway’s contention that design itself is rhetorical in nature and, thus, schools of architecture teach students how to argue. This argumentative education is not only learned through the oral elements of crits or reviews, but also in the process of design itself. “Buildings that lack a ‘proposition’ or idea … are ineffective (as is criticism that evades these issues).”5 He also sees broader implications for understanding the role of rhetoric in architecture: The propositional content of design is a crucial element enabling students to make rational and reasonable decisions as their designs progress. Students who are unable to adequately theme a...