![]()

1 Situating Inclusive Arts

aesthetics, politics, encounters

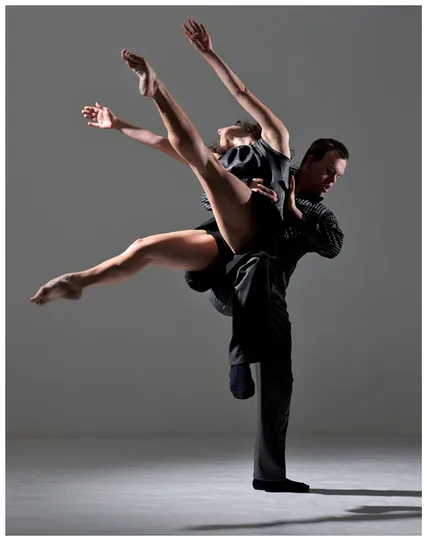

◀ Rocket Artists and Corali

Smudged

Collaborative performance

Tate Modern

London

2008

Introduction

In this chapter we discuss the field of Inclusive Arts and situate it in relationship to associated approaches – including explaining how this work relates to, yet is distinct from, Outsider Art, Socially Engaged Practice, Disability Art, Art Therapy and other associated forms of Contemporary Art. We also reflect on the socially transformative potential of this work for collaborators and audiences. The ideas in this book have been developed from conversations with key practitioners, artists and commissioners in the field of Inclusive Arts, and from Alice’s twelve years of experience working alongside the learning-disabled Rocket Artists.

What is Inclusive Arts?

Inclusive Arts is used here to describe creative collaborations between learning-disabled and non-learning-disabled artists. Inclusive Arts seeks to support the development of competence, knowledge and skills, such that collaborations can result in high-quality artwork or creative experiences. The collaborative processes of Inclusive Arts thus intend to support a mutually beneficial two-way creative exchange that enables all the artists involved to learn (and unlearn) from each other. In essence, it is an ‘aesthetic of exchange’ that places the non-disabled artist in the more radical role of collaborator and proposes a shift away from the traditional notion of ‘worthy helper’. Through redefining this role, and shedding the notion of the formally trained ‘expert’ artist, we try to explore the valuable and skilful contribution that learning-disabled artists can bring to the arts. Of course, collaborative forms of Inclusive Art are just one of a number of ways in which learning-disabled artists practice, but we think when collaboration happens between learning-disabled artists and their non-disabled collaborators it should be recognized and celebrated, not downplayed.

Inclusive Arts is an important field of creative practice because it can help realize the creative potential of people with learning disabilities and facilitate modes of communication and self-advocacy. The processes involved in producing Inclusive Art may promote new visions of how society might be. This does not mean that Inclusive Arts pursues a singular aesthetic effect or social goal. As the conversations and illustrations of practice begin to emerge in this book, Inclusive Art productions (just like other forms of Contemporary Art) can be beautiful, life-affirming, funny, disorientating, upsetting, ironic, sexual, pleasurable, disturbing, distancing, loving, legible, illegible, or all of the above.

Not all Inclusive Art is considered good art or good socio-political practice. Rather, Inclusive Artwork must negotiate a difficult set of relations with disablism, stereotype, cliché, essentialism, exclusion and voyeurism. As in all artistic experimentation, there can be failures. However, this book illustrates some key successes and reflects on the ingredients that have helped the Rocket Artists get their work to the Tate and the Southbank, and reveals how other collaborative partnerships produce the high-quality, high-profile work that is illustrated here. Of course, the paradox we inhabit is that the term Inclusive Arts presupposes exclusion. In a better world, Inclusive Arts would be such an everyday form of practice that it would not need to be given this name; rather, it would be considered an art form that engages with the productivity of difference and the challenges of communication (in its most expanded sense).

▶ Chris Pavia, Lucy Bennett Stopgap Dance Company UK Trespass 2011/2012

Why use the term 'Inclusive Arts'?

We agonized over whether to use the term Inclusive Arts in this book. There are problems with the term and its association with certain oppressive or tokenistic inclusion agendas. In fact, social inclusion policies and an associated politics of diversity have had both negative and positive consequences for those people regarded as ‘needing including’. For example, Ahmed (2012) identifies how discursive commitments to inclusion and diversity in certain institutional contexts are ‘non-performatives’ which do not bring about what they name. And in the United Kingdom, instrumental arts and social inclusion projects have come under heavy criticism from a range of quarters for being neither good art, nor good social work (Belfiore 2002; Bishop 2006).

▲ Glad Theatre Glad Foundation Denmark The Shadows 2012

Glad Theatre challenges actors and audiences by creating raw and courageous productions.

In contrast to these rather bleak accounts of arts and inclusion agendas that have circulated in Britain in recent years, illustrated here are examples of highly successful, genuinely collaborative projects that use the ‘aesthetics of exchange’ to explore the world views of collaborators, foster genuinely meaningful dialogue, show what inclusion can look like ‘in the doing’, and question the nature of social reality. We think such projects are a success because they are underpinned by highly skilled and attuned facilitators who have a long-term commitment to this field (discussed in more detail in Chapter Three). We considered other terms to describe this practice, such as ‘interaction’, ‘the aesthetics of encounter’, or ‘side-by-side collaboration’. However, we chose to continue to use the term Inclusive Arts because it is simple and many existing groups that practice collaboratively identify with it.

Of course, we recognize that in the practice of Inclusive Arts there will always be moments of separation, integration, inequality, inclusion and exclusion – these occur through the space, with other people and with the materials that are being used. There is no perfectly inclusive project – if it was that easy we wouldn’t have had to write a whole book about it. Therefore, in this book, Inclusive Arts describes something of the operating principles, practices and ideals that people who work successfully alongside people with learning disabilities share: the practices and their effects are what matter, where one aim is to minimize exclusion and find a plane of equality (Ranciere 2009) through the practice of art.

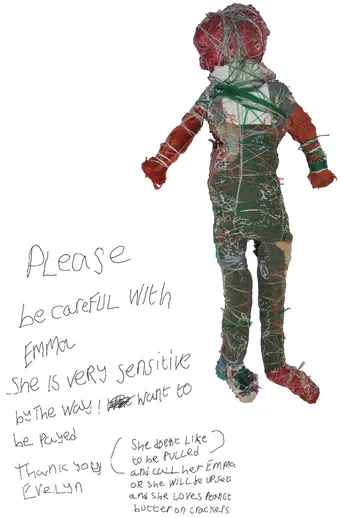

▶ Evelyn Morrissey KCAT Ireland Emma Textiles 180 x 68 x 12cm 2012 With shipping care note

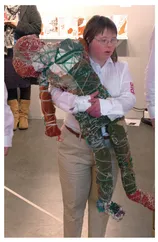

▼ Bethan Kendrick with Emma, Side by Side performance, Southbank Centre, London, 2013

What sorts of inclusions occur through Inclusive Arts Practice?

For the learning-disabled Rockets Artists and their collaborators, the sorts of inclusions that are operating in the studio or other art space are two-way – at times the Rockets are generously including other artists into their own creative worlds, at other points the Rockets and the art students are sharing their knowledge of particular practices and techniques. Such collaboration doesn’t necessarily mean 50:50; rather, it can mean each person bringing complementary skills to a project. This can include choreography, company management and curation.

Interestingly, what we have also witnessed through the Rockets, and through our experiences of other Inclusive Art groups, is that the inclusions that occur in the practice of art making are not limited to the relationships between people. Rather, they also encompass the relationships held with the art materials, processes, technologies and spaces that are being used – certain materials, technologies and studio spaces can literally be more accommodating and thus more inclusive than others. In this way, there is a materiality to the interactions and forms of ‘inclusion’ (broadly conceived) that are occurring. In Chapter Three we explore this point in more depth and reflect on how certain materials and practices aid the process of Inclusive Art making.

Learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, learning-disabled or learning difficulty? Some notes on terminology

In this book the terms ‘people with learning disabilities’ and ‘learning-disabled artists’ are used. The term ‘people with learning disabilities’ reflects current policy discourse in the United Kingdom, and is the term most often used to describe people who have a cognitive condition that significantly affects the way they learn new things. Using ‘people with’ helps to emphasize that this diverse group are people first and foremost. These learning disabilities are often defined on a spectrum, from mild to moderate or severe. Some people with so-called mild learning disability can talk easily and look after themselves. However, people with profound and multiple learning disability may find it extremely challenging to communicate or may have more than one disability. In England, the Department of Health estimated that 65,000 children and 145,000 English adults had severe or profound learning disabilities, and 1.2 million had mild or moderate learning disabilities (Department of Health 2009).

The term ‘learning-disabled artists’ is used in this text to indicate that people with learning disabilities are disabled by society, including the structures and institutions of learning that exist in society. This reflects the insights of the social model of disability (although for a fuller discussion see Goodey 2011). What is most important to note is that learning disability is a socially constructed, historically contingent and contested category of being human. Language is dynamic, and even new terminology for disability that aims to dignify difference tends to be quickly appropriated and used negatively due to fear of difference (Sinason 2010). In the United States, the term ‘intellectual disability’ tends to be used, the term learning disability referring only to those people with relatively mild learning difficulties such as dyslexia. While in the United Kingdom, despite alternatives such as ‘intellectual disabilities’ or ‘learning difficulties’ being proffered by advocacy movements and used elsewhere in English-speaking countries, ‘learning disability’ continues to be the predominant term in policy, medical and psychological discourse (Emerson and Hatton 2008).

Thus our decision to use the term ‘people with learning disabilities’ in this book is pragmatic – it is widely recognized by those who work in the field in the United...