![]()

Manga in Japanese History

KINKO ITO

Manga, or Japanese comics, have traditionally been a significant part of Japanese popular culture. However, Japanese comics do not exist in a vacuum; they are closely connected to Japanese history and culture, including such areas as politics, economy, family, religion, and gender. Therefore, they reflect both the reality of Japanese society and the myths, beliefs, and fantasies that Japanese have about themselves, their culture, and the world. The history of manga shows how they reflect and shape Japanese society and how they came to be what they are today.

Antecedents of Manga in Premodern Japan

Manga has a very long history in Japan that begins with caricature. The Japanese word fūshi (caricature) refers to criticizing or slandering the defects and shortcomings of society or of particular people. The word fūshi-e or “caricature pictures” refers to witty and sarcastic pictures that carry out this function (Shinmura 1991, 214). For example, Hōryūji temple was built in 607 and was rebuilt in the eighth century after a fire. In 1935, caricatures of people, animals, and “grossly exaggerated phalli” were found on the backs of planks in the ceiling of the temple (Schodt 1988, 28). Another temple, Tōshōdaiji, also has ancient caricatures suggesting that exaggerating features for humorous effect was a popular pastime (Kawasaki 1996, 8).

The most famous early caricature that many scholars consider a prototype of the manga form is Bishop Toba’s (1053–1140) Chōjū giga (The Animal Scrolls). This work is a four-volume monochrome picture scroll (emakimono) of humorous brush-and-ink drawings of birds and animals. The scrolls show frogs, hares, monkeys, and foxes parodying the decadent lifestyle of the upper class. In one of the pictures, a frog is wearing a priest’s vestments and holds prayer beads and sutras while other “priests” are losing at gambling or playing strip poker.

Later picture scrolls take a more serious treatment of the subject of religion, such as the Gaki zōshi (Hungry Ghost Scrolls), drawn in the middle of the twelfth century, and the Jigoku zōshi (Hell Scrolls), painted at the end of the twelfth century. Both Gaki zōshi and Jigoku zōshi instruct pictorially the Buddhist notion of transmigration in the six realms of existence. The Gaki zōshi depicts the realm of the pretas (hungry ghosts) who are suffering from hunger, and the Jigoku zōshi realistically shows the fearful realm of hell to be avoided at all cost (Shinmura 1991). Jigoku-e, or “hell pictures” used caricature, but the intent was to teach children basic Buddhist doctrines and ethics by showing scenes from hell. These “hell pictures” became very popular during the Tokugawa period; much like today’s informational manga (jōhō manga), they used pictures with accompanying manga for instructive rather than comédie purposes (Shimizu 2002). Unlike today’s mass-oriented manga, however, medieval emakimono were seen by only a handful of elites, such as “the clergy, the aristocracy, and the powerful warrior families” (Schodt 1988, 32).

An Ōtsu-e (Ōtsu picture) of an ogre chanting a Buddhist sutra (oni no nembutsu), typically sold to travelers during the Tokugawa period.

(Reproduced with permission from the Kawasaki City Museum)

With the Tokugawa period (1603–1867), woodblock-printing technology allowed a wide variety of caricatures and picture stories to be produced for commoner audiences. The town of Ōtsu near Kyoto sold Ōtsu-e (Ōtsu Pictures) to travelers who were on the main road from Kyoto to the north in the mid-seventeenth century. Ōtsu-e started as simple Buddhist-inspired folk art for prayer, printed using a crude and primitive process that was available to ordinary people (Kawasaki 1996, 10; Shinmura 1991, 329). Since the Tokugawa government was actively persecuting Christians, many people purchased ōtsu-e to have a proof that they were not heretics. These pictures grew in popularity and developed themes that were secular, satirical, and sometimes scandalous, appealing to the many travelers along the Tōkaidō highway, who purchased them as souvenirs (Shimizu 1991, 23).

Toba-e pictures, witty and comical caricatures from everyday life, appeared in Kyoto during the Hōei period (1704–1711). The name Toba-e suggests that they were considered to be in the tradition of Bishop Toba; during the eighteenth century, their publication in Osaka marked the beginning of a commercial publishing industry that was based on woodblock-printing technology. In the succeeding centuries, Toba-e spread from Osaka to Kyoto, then Nagoya, and finally to Edo (today’s Tokyo).

From the Genroku period (1688–1704) to the Kyōhō period (1716–1736), akahon also became very popular. Akahon literally means “a red book” with a red front cover. Akahon is one example of a popular and lowbrow genre called kusazōshi that were commonly referred to as “red books,” “black books” (kurvhon), “blue books” (aohon), or “combined volumes” (gōkan), based on the color of the cover and the specific method of bookbinding.

Akahon were picture books based on classic fairy and folk tales such as “The Peach Boy,” “The Battles of the Monkey and the Crabs,” “The Sparrow’s Tongue,” “Click-Clack Mountain,” and “How the Old Man Lost His Wren.” There were also smaller versions of akahon called akakohon or “small red books,” and hinahon (dolls’ books). Later, akahon evolved into picture books for adults consisting mostly of pictures with little text. Both Toba-e and akahon became popular commodities, whether they were hand-drawn or woodblock printed (Shinmura 1991).

Schodt (1991) sees modern manga as the direct descendant of kibyōshi and ukiyo-e. Kibyōshi (yellow-jacket books) like the red, black, and blue books that preceded them, developed from children’s picture books. Kibyōshi, which mocked conventional mores through humor, jokes, satire, and cartoons, were often published as a series of monochrome paintings with captions. Kinkin sensei eiga no yume (Mr. Kinkin’s Dream of Prosperity), written by the humorous poet and ukiyo-e painter Harumachi Koikawa (1744–1789), was a groundbreaking work. In the story, Mr. Kinbei (his nickname in the story is Kinkin), standing before the store front of Awamochiya, daydreams that he gets adopted by the rich Izumiya family and attains the height of prosperity. He leads a fast life but eventually gets kicked out of his adopted family (Shinmura 1991, 701, 843).

Ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) is a genre of folk illustrations that were especially popular among the urban merchant class during the Tokugawa period. Early ukiyo-e were painted, but it was woodblock printing that made them truly popular in the late seventeenth century. The most common ukiyo-e feature actors, famous beauties, and sumo wrestlers as well as landscapes, birds, and historical themes.

In 1765, Harunobu Suzuki started multicolor woodblock printing, marking the beginning of the golden age of ukiyo-e color prints (Reischauer 1990; Schodt 1988; Shinmura 1991). Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), born in Edo in 1760, excelled in sketches and dynamic compositions in the ukiyo-e style. Hokusai’s ukiyo-e masterpieces include multicolored woodblock prints of flowers and birds, “The Thirty-six Sceneries of Mt. Fuji,” illustrations for novels, and other original paintings and drawings of beauties and samurai. Hokusai’s Furyū odoke hyakku, a series of about a dozen woodprints, was drawn in the Toba-e style. The characters had extremely long and slim hands, limbs, and legs to give the readers a sense of dynamic action. Hokusai published his fifteen-volume Hokusai manga between 1814 and 1878. While this work did not use the Toba-e style, it did use caricature to criticize social conditions after the Tempo period (1830–1844), which was characterized by famine, a rise in prices, and peasants’ riots. Hokusai was the first to coin the term manga, and his book became a bestseller.

Manga started to permeate people’s everyday lives along with giga ukiyo-e (funny or playful picture ukiyo-e) and illustrated newspapers. In 1867, the last year of the Tokugawa shogunate, the Japanese government displayed Hokusai manga and other picture books at the World Exposition in Paris (Reischauer 1990, Schodt 1988, 1991; Shimizu 1991; Shinmura 1991; Yasuda 1989), a sign of how these popular picture genres were becoming increasingly accepted by the authorities as part of mainstream Japanese culture.

Other types of pictures were more controversial. Shunga (spring drawings) was a popular type of ukiyo-e during the Tokugawa period; these woodblock print pictures show uninhibited Japanese sexuality and erotic materials. The lovers depicted in the shunga are rarely naked. They are clad in sensuous, loose-fitting kimonos, which were supposed to heighten sexual attraction. The naked sexual organs are exaggerated and it is obvious that the focus is the sexual act itself. Ecstasy is depicted by the comments next to the picture or by the facial expressions of the lovers. Shunga depict various kinds of lovemaking, including lesbian sex (which was then considered perfectly natural), ménage à trois, voyeurism, female autoeroticism, male homosexuality, and bestiality. Shunga also served as sex manuals for brides-to-be (Wilson 1989; Shirakura 2002). The kind of erotic caricature apparent in the genre also appears in contemporary adult manga (Ito 1994, 1995, 2002).

While the Tokugawa government had banned travel abroad in 1636 and Japan closed its doors to most other nations, in July 1853 the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan and demanded that Japan open its ports. A tremendous amount of Western influence poured into Japan, and manga was profoundly influenced.

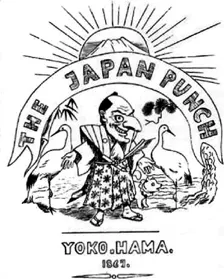

Charles Wirgman (1832?–1891) created and published the Japan Punch in Yokohama in 1862. Wirgman was a British correspondent for the Illustrated London News and a cartoonist who also taught oil painting to Japanese students. His cartoons depicted the tension and conflict between Japan and the West, and the Japan Punch continued for twenty-five years and 2,500 pages. It was popular among Western expatriates and Japanese residents alike, and is an indispensable resource for understanding the rapidly changing Japanese society at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912). But it also illustrates the diffusion of Western culture into Japan (Kawasaki 1996; Schodt 1988; Shimizu 1991). Wirgman’s cartoons show the ways in which foreign influences were assimilated to create modern manga. For example, Wirgman’s cartoons often used word balloons, which many native Japanese artists, like Kyōsai Kawanabe, adapted to then-own work. Kawanabe’s Western-style political cartoons eventually became a staple in Japanese newspapers, such as Nihon bōeki shimbun (The Japan Commercial News).

The cover of Charles Wirgman’s The Japan Punch. Note that the originally European Punch no longer appears in jester’s costume, but is dressed and coiffured in traditional Japanese style.

(Reproduced with permission from the Kawasaki City Museum)

Manga in Modern Japan

Up until the Taishō period (1912–1926), what we now call manga was referred to as ponchi (punch) and ponchi-e (punch picture) as well as Toba-e, Ōtsu-e, Odoke-e, kokkeiga (funny pictures), and kyōga (crazy pictures) (Shimizu 1991, 16). A French humor magazine called Tobae, which satirized Japanese government and society, was started in the foreign settlement in Yokohama in 1887 by Georges Ferdinand Bigot (1860–1927), a French painter. Although Tobae ceased publication after only three years, its style proved to be highly influential. Bigot arranged his cartoons in a narrative sequence, which (along with Wirgman’s word balloons) led to modern Japanese comics (Kawasaki 1996, 80; Schodt 1988, 40; Shinmura 1991, 214; Shimizu 1991, 82–87).

Japanese manga have long been used for satire; this was particularly evident during the “freedom and people’s rights movement” (jiyū minken undō) in the Meiji period. Taisuke Itagaki, Shōjirō Gotō, Shimpei Etō, and other political leaders, influenced by European thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Uberai British philosophers, formed the first political party, the Aikoku Kōtō, in 1874. Around the same time, “manga journalism,” which engaged in political satire, began to appear in Japanese newspapers and magazines. One early example is the E-shimbun Nihonchi (Picture Newspaper Japan), a magazine first published in 1874 that closely imitated the Japan Punch.

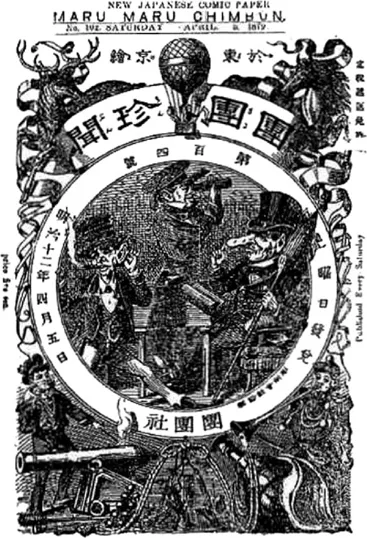

The front cover from Fumio Nomura’s Maru maru chimbun.

(Reproduced with permission from the Kawasaki City Museum)

Groups like the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement used manga to get their antigovernment message out. For example, in 1877 Fumio Nomura first published Maru maru chimbun, a weekly satirical magazine. Chimbun satirized not only the Meiji government, but also the emperor and the royal family. Since he had violated the Japanese zanbōritsu (slander law) and the shimbunshi jōrei (the press laws), Nomura soon found himself in serious trouble (Reischauer 1990; Shimizu 1991; Shinmura 1989; Yasuda 1989), yet the controversy increased the magazine’s sales. Unlike Tobae, which cost eighty sen per issue, Maru maru chimbun was only five sen per issue and thus targeted the masses (Shimizu 1991, 95). It should be noted that various technological innovations—including zinc relief and copperplate printing, lithography, metal type, and photo engraving—made such magazines possible at this time. The developing t...