It has become something of a cliché to ascertain that we now live in an urban world where most of the world’s population resides in settlements described as urban. Given this, it follows logically that the majority of research in human geography relates to cities in some shape or form, and comments on the social, economic or political circumstances faced by urbanised populations. Likewise, most geographical knowledge production occurs in universities and research institutes based in cities, making the city both a key venue of geographic knowledge production, as well as its principal field site. But although most human geography research can be described as urban – in the sense that it is produced in or relates to cities – a surprisingly small amount of contemporary geographical work is concerned with defining the city itself. To put this somewhat differently, while there is much geographical work carried out in cities that contributes to social, economic, political or cultural theory, most say very little, if anything, about urbanisation as a process. In fact, in the vast majority of the human geographical research that has the city as its context or backdrop, the question of what constitutes ‘cityness’ remains elusive.

This said, there are multiple theories of urbanisation developed by sociologists and urban scholars over the last 150 years or so which provide some inroads into this issue. Crucially, these theories do not define cities in terms of what they contain (i.e. internal attributes like population size or density) but instead theorise urbanism as a distinct ‘way of life’, fundamentally different from the forms of life evident in more traditional, rural societies. In these theories, there is a degree of conflation between the emergence of cities and the emergence of modern societies, with some accounts inferring these are one and the same (i.e., modern society is a society of cities). This means that some traditional theories of urbanisation say remarkably little about the role of cities in creating, and sustaining, modern society (Brenner 2009). Redressing this, new approaches to the study of urbanisation emerged from the 1970s onwards which explicitly addressed the ‘urban question’ – namely, what role do cities play in the processes of production and exchange that are integral to capitalist society? This is a question at the heart of urban political economy, a theoretical approached largely indebted to the ideas of Karl Marx. Reflecting the current hold Marxist and neo-Marxist thought has on urban studies, this chapter charts the shift from descriptive to more critical urban theories, and the move from questions of what the city is, to what the city does. It starts, however, by describing the relationship of modernity and the city, exploring the contention that urbanisation has created distinctive and deleterious forms of social life.

MODERNITY AND URBANISATION

There is little consensus as to when or where the first cities emerged: candidates include varied regions in Southwest Asia, from the highlands of Mesopotamia through to the fertile valleys of the Sumerian civilisation. There is also no clear agreement as to why cities first formed. Perhaps it was for defensive reasons; maybe it was a response to the emergence of a political or military elite or a function of economic imperatives that required the creation of trading markets the type of which simply could not be accommodated in a village. Indeed, for archaeologist Gordon Childe (1936) the ‘urban revolution’ was only made possible by the creation of storable food surplus, and the attendant needed to evolve systems of exchange and barter. However, others have suggested that the search for a single explanation is futile, with different social, cultural and economic factors combining to encourage the originary growth of cities in different global regions.

We return to some of these debates about urban forms and functions in later chapters. However, at this point, it will suffice to say that cities have been in existence for a long time. This given, it is surprising that it took so long for a distinctive body of urban theory to emerge. Indeed, it was not until the nineteenth century that the city began to be taken seriously as a distinctive and important object of academic study. Perhaps the main reason for this is that until that time the share of the global population living in cities remained relatively small. The rapid urbanisation of the nineteenth century (sometimes termed the second ‘urban revolution’) changed this, first evident in the economically dominant states of the European heartland. In this period, for instance, Britain experienced the most rapid and thorough urbanisation (Box 1.1) the world had witnessed to that point. The 1851 Census of the Population of England and Wales revealed a watershed event: for the first time, more people lived in towns than in the countryside. Furthermore, 38 per cent of Britain’s population lived in cities of 20,000 or more, and by 1881, this figure topped 50 per cent. From 1801 to 1911, the urban population increased nearly by a factor of ten, from 3.5 million to 32 million. Nowhere was this more evident than in the capital, London, which surpassed Beijing to become the world’s largest city in 1825, and by 1900 had 6,480,000 occupants (2 million more than its nearest rival, New York).

Box 1.1 URBANISATION

Urbanisation conventionally refers to the shifting balance between urban and rural living in favour of the former. In 1996 The United Nations famously declared that the world was entering an ‘urban millenium’ predicting that, for the first time, the population living in cities would surpass that living in the countryside (something that reportedly happened in 2008, when the urban population exceeded three billion worldwide: in 1900 only 13% or around 220 million people lived in cities). In China, the urban population increased from around 20% to 50% of the total population between 1982 and 2012, while the urban population of India is predicted to have doubled from 20% to 40% by 2030.

Today, global population growth is overwhelmingly absorbed by cities, with at least thirty-five cities now boasting more than 10 million people (there were only around ten in 1985). This type of rapid urbanisation can create significant social, economic and environmental problems. For example, city living is characteristically more dense than rural living, and while this can allow for certain efficiencies in the delivery of urban services such as education, hospitals, housing and public transport, this can also place massive pressure on urban infrastructures. In many of the so-called megacities of the global South, this is evidenced in the growth of shanty-towns and areas of informal housing which often lack basic infrastructure such as electricity, water or sewerage. Even in so-called ‘developed’ world cities, the excessive reliance placed on stretched urban services is brutally exposed in moments of systemic failure (such as the floods that engulfed New Orleans in 2005 or the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2011). The ability of cities to cope in such situations is referred to as urban resilience, something of major significance given rapid population growth, accompanied by urban sprawl, makes it potentially harder to plan cities that reduce their inhabitants’ exposure to possible risks.

Reading: Pelling 2003

It is quite conventional to suggest that the major transformation that triggered this rapid shift in settlement from the country to the city was the ‘industrial revolution’, which ushered in a world where manufacturing was the economic driving force. In industrial societies, the power of merchants, craftsmen and religious guilds was supplanted by the power of industrial capitalists making the commodities of an industrial age (Pirenne 1926). These industrialists imposed their identity on the city in a new landscape of factories, workshops and machinery, around which were spun new webs of transportation and power. Both industrial employers and employees alike found themselves in an environment far removed from rigid social and spatial forms associated with medieval cities: the industrial city also offered apparent social mobility, being a place where wealth could be made – or lost – quickly. It, hence, offered new contrasts of wealth and deprivation, from the spectacular suburban homes of the nouveaux riche bourgeoisie to the slums and rookeries of the struggling working class. These contrasts were also evident in the new public spaces of the city, where the upper and middle class rubbed shoulders with labourers and the ‘street dwellers’ who relied on their wits to make a living among the detritus of urban life (e.g., rag pickers, hawkers and beggars). The industrial city was also characterised by perpetual transformation, with new ideas, technologies and built forms constantly transforming people’s sense of identity (Berman 1983).

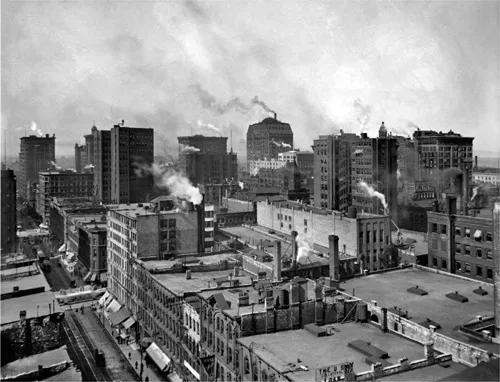

No wonder contemporary commentators struggled to describe emerging cities using existing language: in short, their size, appearance and complexity rendered them a new species that demanded to be classified, catalogued and ultimately, diagnosed. Notable examples here included Manchester – the English market town that transformed into the world-renowned ‘cottonopolis’ in a few short years, growing from a population of 15,000 in 1750 to over 2 million by 1900. For Friedrich Engels, who wrote The Condition of the Working-Class in England while in the city from 1842–1844, Manchester was the prime example of the industrial city – the ‘first manufacturing city of the world’ – but also the scene of ‘filth and ruin’ capable of generating horror and indignation (Engels 1845: 67). When visited by French political commentator Alexis de Tocqueville in 1840, Manchester was similarly described as a ‘putrid sewer’ from which ‘pure gold flows forth’, a city where ‘humanity achieves for itself both perfection and brutalization’. Across the Atlantic, Chicago was to gain a similar reputation. Effectively founded in 1830, Chicago’s population nonetheless surpassed one million in 1890, with sociologist Max Weber (1905: 67) writing, ‘the town goes on for miles and miles until it loses itself in the vastness of the suburbs going on as far as the eye could see’ (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Heart of Chicago’ (Detroit Publishing Company, c. 1901. With permission of Richard Burns, Bury Art Gallery and Museum)

In the late nineteenth century, Manchester and Chicago were ‘shock cities’, settlements where the environmental and social impacts of rapid urban growth provoked both fear and wonder (Platt 2005). They were then understood as thoroughly modern, a term used retrospectively to describe a particular set of aesthetic, social and cultural norms:

There is a mode of vital experience – experience of space and time, of self and others, of life’s possibilities and perils – that is shared by men and women all over the world today. I will call this body of experience ‘modernity’. To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world – and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are. Modern environments and experiences cut across all boundaries of geography and ethnicity, of class and nationality, of religion and ideology: in this sense, modernity can be said to unite all mankind. But it is a paradoxical unity, a unity of disunity; it pours us all into a maelstrom of perpetual disintegration and renewal, of struggle and contradiction, of ambiguity and anguish.

(Berman 1983: 1)

The ambivalence of the modern was captured in some of the emerging cultural forms associated with urban life, including photography, literature and landscape art, but particularly cinema (see Chapter 7). For example, Barbara Mennel (2008) cites the film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City by Walter Ruttmann (1927) as a successful attempt to capture the social and spatial qualities of rapidly-changing modern cities. The film portrays a day in the life of Berlin, organised in five acts focused on the life of the city itself. As she writes, ‘Human beings in the metropolis are continually subordinated to the material dimension of modernity in shots of modernist architecture, industrial design, and electricity’ (Mennel 2008: 39). The film emphasises the anonymity of the city through shots of crowds on the street, the flows of pedestrians and the arrival of commuter trains from the suburb, reducing people to recognisable ‘types’: the commuter, the worker, the shopper and, in one famous scene, the prostitute. Through such moves, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City suggested that cities commodified human experience, reducing people to the status of functional parts of a machine or, at worst, objects to be bought or sold.

Such representations stress the ambivalent experience of space and time associated with the modern city, and the contrast they offered with premodern ways of life. In imaginative terms, these traditional ways of life were deemed to persist in the rural, where the ties that bound family, land and labour apparently remained strong. This was little commented on by geographers, in contrast to sociology, a discipline that coalesced in the nineteenth century around the question of the difference between urban modernity and rural tradition (Tonkiss 2005). From its very inceptions, sociology questioned whether it was possible to talk about a distinctive urban way of life, and, moreover, whether this was a way of life common to all cities – or even all parts of a single city (Savage et al. 2003). Although some sociologists addressed these issues tangentially, and were more concerned with exploring the nature of modern life rather than urban life per se, the inevitable conflation of modernisation, urbanisation and industrialisation established some important ideas about urbanism as a way of life. Foremost, here was the idea that cities were larger, more crowded and socially mixed than rural settlements, bequeathing them a less coherent and more individualised character.

This idea of the city as representing the antithesis of traditional ruralism is perhaps most associated with the sociologist Ferdinand Tonnies (1887). He described two basic organising principles of human association. The first was the gemeinschaft community, characterised by people working together for the common good, united by ties of family (kinship) and bound by a common language and folklore traditions. At the other end of the spectrum, Tonnies posited the existence of gesellschaft societies, characterised by rampant individualism and a concomitant lack of community cohesion. Though Tonnies couched the distinction between gemeinschaft and gesellschaft in terms of a preindustrial/industrial divide rather than a rural/urban one, his description of gesellschaft societies appeared to describe industrial cities where the extended family unit was supplanted by the ‘nuclear’ household – a unit of economic and social reproduction that encouraged individuals to focus on their own family’s problems and to ignore the affairs of others.

Tonnies was describing two ends of a social continuum, not positing a binary distinction. Nonetheless, the idea that social cohesion and sense of community would be less evident in a city than the country proved a persuasive one, and one which was to guide sociologists as they further explored the nature of modern urban living. Indeed, it is one that has echoed down the years, finding more recent expression in influential works including Robert Putnam’s (1995) Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community, which alleges that cities have bred a rampant and narcissistic brand of individualism. Like Tonnies, many urban sociologists have then mourned the lack of social cohesion apparent in cities, revealing a nostalgia for traditional ways of life that appear to be fast disappearing.

However, there have always been notable dissenters to the idea that cities diminish social relationships. For instance, one of the ‘founding fathers’ of sociology, Emile Durkheim, developed a model of social order somewhat at odds with that of Tonnies. For Durkheim (1893), traditional, rural life offered a form of mechanical solidarity with social bonds based on common beliefs, custom, ritual, routines and symbols. Social cohesion was then based upon the likeness and similarities among individuals in a society. Durkheim argued that the emergence of the industrial city-state signalled a shift from mechanical to organic solidarity, with social bonds based on specialisation and interdependence. Durkheim consequently suggested that although city – dwellers often have different values and interests, they come to rely upon one another performing specific tasks. Hence, in contrast to feudal and rural social orders, urban society encouraged a complex division of labour (where different people specialise in different occupations) creating greater freedom and choice for individuals.

Read optimistically, Durkheim’s work pointed to a new kind of solidarity with people brought together by mutual interdependence. However, a more common prognosis was that cities were essentially cold, calculating and inhumane. For example, Georg Simmel (1858–1918) described the impacts of the city on social psychology, noting that the city required a complex series of adaptations to cope with its size and complexity. In his much-cited essay, ‘The metropolis and mental life’, originally published in 1903, Simmel argued that the unique trait of the modern city was the ‘intensification of nervous stimuli with which city dweller must cope’. Describing the contrast between the rural – where the rhythm of life and sensory imagery was slow – and the city – with its ‘swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli’ – Simmel hypothesised that individuals psychologically adapt to urban life. Most famously, he spoke of the development of a blasé attitude, which can perhaps be best described as the attitude of indifference which (most) urban dwellers adapt as they go about their business:

Instead of reacting emotionally, the metropolitan type reacts primarily in a rational manner … Thus the reaction of the metropolitan person to those events is moved to the sphere of mental activity that is least sensitive and furthest removed from the depths of ...