![]()

1

Age Discrimination

Age discrimination occurs when one particular age group is treated differently to another age group on the grounds of chronological age. It is possible for this different treatment to be benign, as in giving reduced admission rates for cinemas to older persons. It is also possible for it to be less favourable treatment when, for example, a person is refused medical treatment because they are deemed to be too old to benefit from it.

Age discrimination is a practical manifestation of ageism, which is about having an essentially negative image of older people. A good definition is contained in a UN report on ageing. It states that: ‘Ageism reinforces a negative image of older persons as dependent people with declines in intellect, cognitive and physical performance. Older persons are often perceived as a burden, a drain on resources, and persons in need of care’.1 Ageism is primarily ‘an attitude of mind which may lead to age discrimination’.2 The word ‘ageism’ is said to have first been used by Robert Butler MD in 1969. Butler wrote a short article3 about the strongly negative reaction of white affluent middle class residents to a proposal for a public housing project for the ‘elderly poor’ in their district. He described ageism as: ‘Prejudice by one age group against other age groups’. Although he highlighted the issue of ageism the events that he described appeared also to be a mixture of prejudice based upon race and class.

Age discrimination has, of course, both an institutional and an individual perspective. A report by the Equality Authority of Ireland stated that: ‘Ageism involves an interlinked combination of institutional practices, individual attitudes and relationships.’

Institutional practices in this context can be characterised by:

• The use of upper age limits to determine provision or participation.

• Segregation, where older people are not afforded real choices to remain within their communities.

• A failure to take account of the situation, experience or aspirations of older people when making decisions, and a failure to seek to ensure benefit to them as a result of an over emphasis on youth and youth culture; and

• Inadequate provision, casting older people as burdens or dependents.

Institutional practices can shape, and be shaped, by individual attitudes based on stereotypes of older people as dependent, in decline or marginal. Some of these practices can also have a detrimental impact on an older person’s sense of self worth.4

These institutional manifestations of age discrimination are based on group stereotypes. Upper age limits may be imposed for health care or for employment purposes, for example, because of a belief that it is correct to treat older people less favourably than others. This may be the result of an idea that older people have outlived the useful part of their lives and that society should somehow allocate its resources to those that have something left to contribute. Older people may be segregated and regarded as a drain on the resources of the community. There is no attempt in these practices to differentiate one older person from another. Like all discriminatory practices it can accept that there are exceptions to the general rule, but the general rule results in treatment relying upon an unacceptable criterion. There is little attempt to differentiate between one older person and another. It is a key argument in this book that age legislation tends to homogenise age groups, so that we end up talking about the problems of older people in general, rather than reflecting on the diversity within each age group.

Individuals’ lives are defined by age:

Our lives are defined by ageing: the ages at which we can learn to drive, vote, have sex, buy a house, or retire, get a pension, travel by bus for free. More subtle are the implicit boundaries that curtail our lives: the safe age to have children, the experience needed to fill the boss’s role, the physical strength needed for some jobs. Society is continually making judgments about when you are too old for something – and when you are too old.5

There are many surveys that show age discrimination taking place, especially in the workplace. One survey showed that some 59 per cent of respondents reported that they had been discriminated against on the basis of the age during their careers.6 One in three respondents to a further survey found that the over-70s were regarded as incompetent and incapable and that more people reported suffering age discrimination than any other form of discrimination.7

In a survey of retired trade union members, almost one third claimed to have suffered age discrimination at work and one in twelve claimed to have been harassed for reasons connected to their chronological age.8 One of the respondents recounted this story:

I was a lecturer in journalism for over 11 years until I was forced to retire last year, despite having no wish to do so. I was told just before my 65th birthday that I would be compulsorily retired at the end of the summer term.

The college, with its usual efficiency, left it too late to advertise for a replacement and they could not find a suitable applicant. At the eleventh hour, as desperation set in, I was asked to stay on. I was very happy to do so because I enjoyed my work and I was very efficient at my job.

I would have been content to carry on for another two or three years and I assumed that, having breached their strict code of retirement at 65, the college would be pleased for me to do so. However, in April last year I was informed that my job was again going to be advertised and I would be forced to retire when a replacement was found. I told the personnel department that it was unfair because they had been more than ready to ignore their mandatory retirement rule when it suited them. They refused and the job was advertised, again at a late hour, and this time they found a suitable candidate although this did not happen until three weeks before the end of the summer term, so I was kept in suspense until shortly before I was due to start my holidays.

There is a sense of frustration in this letter. An experienced and active individual is ejected from employment and almost discarded as a result of the application of a rule based upon a chronological age rather than the merits of the individual.

There are sufficient surveys reported in this book to show that decisions are taken on the basis of an individual’s age, in relation to employment and to the provision of goods and services. One way of reducing this discrimination is to make institutional discrimination unlawful in order to help make individual discrimination unacceptable.

Stereotypes and Discrimination

It has been suggested that the word ‘stereotype’ was first used in the eighteenth century to describe a printing process whose purpose was to duplicate pages of type.9 The usage of the word later developed from the idea of producing further images from a stereotype into reproducing ‘a standardised image or conception of a type of person’.10 The problem with producing this ‘standard image’, or stereotyping, is that individuals are treated as members of a group, rather than being treated as individuals. It is the group to whom we attribute generalised characteristics, which clearly cannot possibly be the characteristics of every individual within that group.

One simple assumption, for example, might be that men are stronger than women. The result of this is that only men might be considered for physically demanding jobs, which in turn may be the higher paid jobs in certain types of employment. The outcome is that women are discriminated against in the selection process and end up earning less than men. The assumption is patently false. Not all men are stronger than all women. Some women will be stronger than many men and so on. The discrimination comes from the stereotyping of women in the first place. It is the allocation of a generalised characteristic to an identifiable group.

The result of employment policies based upon the age of employees is to reduce the participation rate of older people in the job market. These policies encourage them to leave the labour force and discourage them from re-joining it. They may also be responsible for older employees having fewer training opportunities than their younger colleagues. One of the reasons for this may be the stereotypical attitudes that employers have held towards the abilities of employees based upon their age. In one oft quoted survey of 500 companies11 a question was asked about at what age someone would be too old to employ. Of the respondents 12 per cent considered people too old at 40, 25 per cent considered them too old at 50, 43 per cent considered them too old at 55 and 60 per cent felt they were too old at 60. The relationship of these judgements to conventional stereotypical attitudes can be shown in their answers to questions about agreeing or not agreeing with statements. Figures such as the 36 per cent who thought that older workers were more cautious, the 40 per cent who thought that they could not adapt to new technology and the 38 per cent who thought that they would dislike taking orders from younger workers suggest that stereotypical attitudes remain strong. Research indicates that there is little evidence that chronological12 age is a good predictor of performance. An OECD study concluded:13 ‘Age has only a marginal effect on industrial productivity and the variations in productivity within a given age group are wider than variations between one age group and another.’

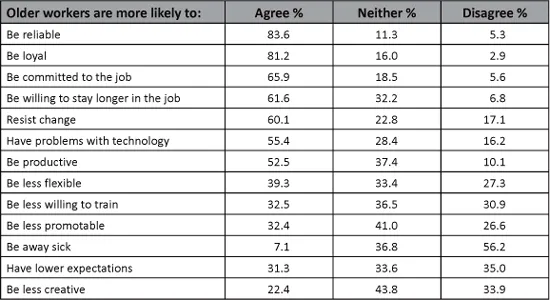

The willingness of employers to attach characteristics to age groups is illustrated by a New Zealand survey covering large and small employers (Table 1.1). Older workers are more reliable, more loyal, more committed and less likely to leave than younger workers. On the other hand, older workers are more likely to resist change and have problems with technology. They may also be less flexible, less willing to train and be less creative than younger colleagues.

Table 1.1 New Zealand survey of age characteristics

The argument is not whether these characte...