CHAPTER 1

Process, Structure, and Ideology

Our primary thesis is that the American political system, built as it is on a conservative constitutional base designed to limit radical action, is nevertheless continually swept by policy change, change that alternates between incremental drift and rapid alterations of existing arrangements.

(Baumgartner and Jones 1993, 236)

Politics is how society manages conflicts about values and interests.

(Brown 1994, 175)

Those who have studied public opinion in the United States have come to two important conclusions. First, the public does not know much about government, politics, and public policy. For example, as we see in Chapter 8, vouchers are one of the most important issues in the educational policy area. Yet according to a report by Public Agenda, very few of the public know anything about vouchers or have heard about them (Public Agenda 1999).

Second, attitudes toward government have deteriorated. Trust in the ability of government, especially at the federal level, to do what is right and what the public wants has declined dramatically since the 1960s (Wills 1999). In 1958, about 78 percent of those who polled said they trusted government to do the right thing always or most of the time; by 2015, that number had dived to 19 percent (Pew Research Center 2015). One of the interesting developments in the 2016 president cycle was how angry and anxious a portion of the population was about the direction of the country. While this is not necessarily new (see Tolchin 1996), it does seem to have increased over the last twenty years or so.

Both of these ideas are important. If the public is ignorant about whether government programs work or even the nature of those programs, it is likely to remain skeptical that anything government does will have a positive effect. Cynicism seems to run rampant. Yet there is much information available about government and public policy. The advent of the Internet has opened up the possibility of discovering more about our society and our government. But the Internet is a mixed bag, as it can also be an important source of misinformation.

To be informed takes time and effort, however, with little apparent reward. Generally, we tend to become concerned only when government personally affects us, say those who lived in the Gulf Coast area after Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. If American lives are needlessly lost or the economy is not performing well (the peace and prosperity issues), then we mobilize. And with economic growth not well distributed (see Chapter 2) and concern about terrorist attacks (see Chapter 3), we can see why anxiety, mistrust, and fear have increased. But without these and other direct impacts, we go about our own lives. Because the actions that government takes may have important effects on our lives, this text is designed to help explain and evaluate what government does.

Public policy is a course of action made up of a series of decisions, discrete choices (including the choice not to act), over a period of time. According to David Easton (1965), politics involves the “authoritative allocation of values.” Lawrence Brown (1994), in the second quote opening this chapter, writes that politics has to do with resolving conflicts over interests and values. Both definitions say basically the same thing. Values are things that are important to us, such as money, property, life, and health, and more abstract values such as freedom.

Government is the set of institutions that make these allocations and that resolve these conflicts. The focus of this text is on what decisions governments make and why (and, to a lesser extent, how), and what the results of those decisions are.

Inputs to a political system consist of two types, supports and demands (Easton 1965). Supports include the overall support for a political system (its legitimacy), support for its leaders, and the acceptance of specific policies. The actions of political leaders and the outputs and outcomes of the political system feed these supports: President George W. Bush experienced a considerable loss in public approval because of the Iraq war, the response to Hurricane Katrina, and scandals that hit his administration. President Barack Obama began his administration with very high levels of public support, which began to decline in the weak economy of the recession and the debate over health care reform, though recovering in 2016. The decline in trust, briefly mentioned above, suggests less support, less legitimacy, for the political system (Wills 1999).

Demands are requests for action on the part of the political system and feed directly into the policy process. Both demands and supports can be seen in public opinion polls (supporting or opposing policies or presidential action) and in the behavior of interest groups.

Two types of policy results can be distinguished: outputs and outcomes (Sharkansky 1970). Outputs are the tangible and symbolic results of government decisions. The economic stimulus package passed in early 2009 is an example of a tangible product; a presidential speech is a symbolic output (Edelman 1964). The president says something (a policy statement), but government policy may not necessarily change. President Obama’s continual calls for stronger gun control legislation after mass shootings did not result in new legislation, though he eventually took very modest action via executive orders (see Chapter 7). Outcomes are the results of government outputs. If an economic stimulus package is passed (such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009), does it result in the creation of new jobs and promote economic recovery? What is the result of a presidential speech? Does it satisfy the demands of certain groups? Does the policy have unexpected or unintended repercussions?

Policies can be contradictory (Stone 2012). For example, one portion of the federal government (Department of Agriculture) provides price supports for tobacco farmers. At the same time, another part of the federal government (U.S. Surgeon General) requires warnings that use of tobacco products may result in adverse health consequences. The two policies seem to work at cross-purposes. This frequently occurs in policy making and is due to the different policy dynamics of agencies, legislative committees, programs, goals, and interest groups. Public policy in the United States is rarely cohesive. The reasons for this are the twists and turns of the policy process and the characteristics of the American political system.

THE POLICY PROCESS

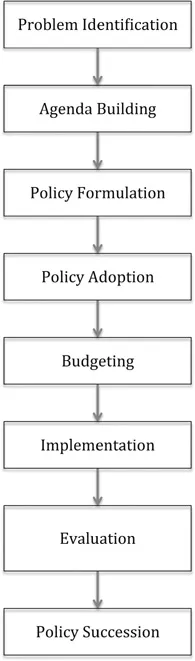

Public policy is the product of a number of steps or phases (Figure 1.1). The course of public policy is a tortuous one; policies may be changed at any step or may fail to pass through a step.

To help explain policy making, the process will be presented in a linear fashion—that is, as if a policy starts at the first step and emerges from the last. The reality is much more complex, and some of these complexities are described at the end of this section.

Critiquing the Process Model

For decades, political scientists have developed a number of models or frameworks to help describe, explain, and develop hypotheses about the policy process, an enterprise that continues (see Anderson 1997; Birkland 2015; Jones 1984; Nowlin 2011; Petridou 2014; Sabatier 1999; Theodoulou and Kofinis 2004). The process or stages model has been criticized for only being able to describe and not explain and especially theorize. It is a criticism that has much validity. For our purposes, the process/stages model acts as an organizing framework to put together much of what happens in the making of public policy. In doing so, we incorporate some of the models along the way to help us understand how we got to where we are in various policy areas.

Figure 1.1 The Policy Process

Problem Identification

The first stage of the policy process is problem identification (Dery 1984; Jones 1984; Rochefort and Cobb 1994). This stage begins with a demand for government action to resolve a problem or take advantage of an opportunity; it is an attempt to get government to see that a problem or opportunity exists.

Two important processes during this phase are perception and definition. Perception is the “registering or receiving of an event” that has consequences for people or groups. Definition is the interpretation of those events, giving meaning to them, making them clear (Jones 1984, 52). But problems do not define themselves (Lindblom and Woodhouse 1993). Someone has to point out that a problem exists and give it meaning. Different people will register the same events in different ways and give them different definitions, so it is important to understand who is doing the perceiving and how that perception is defined.

The definition/perception that goes on in this stage has another vital aspect. Not only do we look at events differently, but we look at those affected by public policies differently depending on their status and resources. This is one of the key insights of a policy framework known as social constructionism. Under social constructionism, it is the interpretation of events, policies, and people that we need to understand (Clemons and McBeth 2009; Rochefort and Cobb 1994; Schneider and Ingram 1997, especially Chapters 5 and 6; Stone 2012). A study of the response to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the U.S. Senate substantiated much of Schneider and Ingram’s theory. Advantaged groups, such as veterans who had contracted AIDS, were treated much differently than deviant groups, such as intravenous drug users. The former group was given benefits or, at most, only symbolic burdens; the latter had burdens imposed upon them (Schroedel and Jordan 1998).

Knowing who does the perceiving and defining offers some understanding of differences in policy proposals. It is also helpful to know what shapes these different perceptions and definitions. Such shaping factors can include the mass media, particularly television and social media such as Facebook and Twitter1; critical life experiences, such as wars and economic hardship (compare the effects of the depression on the generation that came of age in the 1930s with the effects of the economic turmoil of the 1970s on that generation); the process of socialization; and values grounded in religious beliefs and/or ideology. Perhaps more important than these shaping factors is the critical role that the different definitions of policy problems take in structuring the rest of the policy process. Different definitions have different policy implications.

Consider the issue of poverty. There are a number of explanations that can be offered for why poverty exists in the United States. The traditional view is that poverty is the result of moral defects in the individual; the person is too lazy to work. Some have argued that the welfare system has encouraged poverty because it is so much more generous than the low-income jobs available (Murray 1984). For example, Ronald Reagan used to talk about welfare queens driving Cadillacs (Lopez 2014). In a more recent example, former Representative Jason Chaffetz (R.-UT) complained about people who could not afford health insurance but could afford an iPhone (Prignano 2017). Discrimination, lack of job skills, and poor education constitute other possibilities. The breakdown of the traditional two-parent family results in increasing numbers of poor families headed by women, often called the “feminization of poverty.” A Marxist might say that poverty is perpetuated by the capitalist system because it provides a “reserve army of the unemployed,” which discourages those who do have jobs from upsetting the status quo by strikes or slowdowns.

Thus, one problem or issue, poverty, has many definitions or explanations. Each explanation has associated with it a specific policy solution. If poverty is due to moral defects in the individual, then the appropriate policy response might be to do nothing. If the welfare system is viewed as encouraging poverty, then welfare reform of some sort might be justified. If discrimination is the problem, then equal opportunity and affirmative action programs might be useful. If the problem is lack of job skills, then a job-training program should be undertaken. Similar measures could be started to improve educational opportunity. If “feminization of poverty” is the problem, then appropriate policies might focus on child support. If the Marxist explanation is correct, then a replacement of capitalism with socialism should be encouraged. Whoever can define and frame the discussion of an issue will generally prevail in policy disputes.

The fact that problem perception and definition are absolutely vital in understanding American public policy is a dominant theme of this book. Problem definitions can be categorized by ideology, and in each policy area the text examines how issues and problems are identified. As this exploration is conducted, problem definitions tend to fall into a few categories (Stone 2012).

Some problem definitions involve narratives that relate stories of decline or loss of control and helplessness (see Chapter 8 on education and Chapter 9 on equality). Other problem definitions rely on numbers or statistics to make the case for public action; Chapter 4 on poverty is a good example of this, as is education policy (Chapter 8).

Still other problem definitions are based on understanding the underlying causes of a problem; the chapter on poverty could be included here, as well as discussions on the environment (Chapter 6) and crime (Chapter 7). Of course, many problems use all three types of explanations.

Agenda Building

The second stage of the policy process is agenda building. We have some idea of wh...