![]()

Part I

The history

The following seven chapters are designed to provide the reader with a broadly chronological overview of the history of ideas relating to mental health, as well as considering treatment trends throughout the ages. The enduring influence of some of these perspectives and therapeutic approaches will also be discussed.

![]()

1

Prehistoric perspectives

Excising demons

Chapter aims

1.To consider evidence for the use of trepanation in prehistoric cultures as a cure for madness.

2.To discuss the use of trepanation in medieval society.

3.To summarise the contemporary use of trepanation within and outside of mainstream legitimate medical practice.

Introduction

The hole in the skull was rectangular in shape, fifteen millimetres long and seventeen millimetres wide. It was located above the right eye socket, approximately where the hairline might have been of the deceased individual. The impression given was of a literal window on the brain. The neatness of the damage suggested that the usual causes of cranial injury must be ruled out. Accident, disease or attack does not cause such symmetrical penetration. The hole was man made and caused by a type of surgery called trepanning, a practice whereby the skull is penetrated using methods such as boring, cutting, scraping or grooving. This particular specimen, however, was the result of surgery which was conducted between five and six hundred years ago, between 1400 and 1500 ad. Equally surprising was the fact that the individual survived the process by two weeks. Evidence of new growth of bone around the perforation suggested that the surgery was performed whilst the person was still alive and that they did not die immediately as a result of the operation (Fernando & Finger, 2003). There are several proposed reasons as to why this procedure was carried out; it may have been an early form of corrective neurosurgery, it may have been part of a religious ceremony, or it might have been an attempt to trigger a return to consciousness in the unconscious or deceased individual. Another suggestion, and the most popular and enduring interpretation, is that this procedure was conducted in order to permit the escape of evil spirits trapped within the cranium which had been causing aberrant behaviour. The following chapter will consider several competing accounts as to the purposes of trepanation, but our primary focus will discuss its use as a very early attempt to cure madness.

Releasing demons

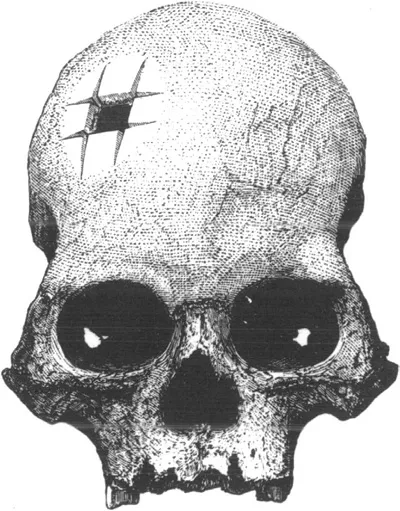

The skull described above was gifted to the travel writer and amateur archaeologist, Ephraim George Squire, on a visit to Peru in the 1870s. It had been in the possession of an avid collector of antiquities called Señora Zentino who had taken it from an Inca cemetery in the Valley of the Yucay (Squire, 1877). Squire recognised its archaeological importance and returned to New York to have it examined by members of the prestigious Academy of Sciences there. Squire also decided to take the skull to one of the most eminent neurologists of the day, Paul Broca. Broca had the position of Professor of Clinical Surgery at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris. He achieved neurological prominence by identifying an area of the brain that plays a key role in language production, and which now bears his name ‘Broca’s area’. Broca was also very interested in the origins of humankind and is credited as being the originator of modern anthropology (Fernando & Finger, 2003). The neurologist examined the skull in detail and confirmed that the individual survived the trepanning process for a week at least with the observation that bone around the hole appeared to have been inflamed as a result of the operation and that this could only occur within a living individual. (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Trepanned Peruvian skull dated between 1400 and 1500 ad. N.B. This is Squire’s illustration of the whole skull, but in reality only the frontal bone containing the trepanned hole was discovered. (This illustration is taken from Squire, E. G. 1877. Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas. New York: Henry Holt, p. 457.)

Squire’s Peruvian skull caused a sensation in the scientific community of the day because it provided evidence that supposed ‘primitive’ civilisations, such as the Incas, practiced a form of surgery not previously considered possible within the limitations of their medical and surgical knowledge. This prompted a revision of previously thought medical practices in such cultures. What was also remarkable to the scientific and medical community of the day was that the trepanned individual survived the operation (Fernando & Finger, 2003). As a result of the Peruvian skull there was widespread curiosity towards trepanned skulls and Broca was at the forefront of this interest. Many important specimens were discovered, some from Neolithic times (the late stone age), which dates them as approximately 5,000 years old and subsequently trepanned skulls have been identified which are dated over 8,000 years old (Lillie, 1998). Examining the pattern of skull damage and repair after trepanning, Broca became convinced that some individuals had undergone the procedure in childhood. In order to test his theory, he replicated a trepanning technique on the skull of a deceased infant using tools which would have been available in Neolithic times, e.g., flint, and found the procedure surprisingly quick and easy. Here, Broca scraped away at the skull until sufficient depth was reached to create an opening. Other methods that had been used in trepanning included making rectangular, intersecting cuts again with flint, but later knives, to penetrate the skull as in the specimen obtained by Squire. Cutting a circular groove in the skull or drilling a series of adjacent small holes in a circular fashion were also used (Gross, 1999).

As to the reasoning behind trepanation, Broca firstly considered whether the holes could be due to accidental or combat related injuries. The neatness of the perforations led him to discount this suggestion. Secondly, Broca considered whether trepanation might be a form of medical surgery, perhaps to relieve intracranial pressure. However this suggestion would entail a highly advanced knowledge of neurological systems and how the brain is affected by damage and disease. This would be beyond primitive cultures. Finally, Broca settled on an explanation tied to the belief systems of ‘primitive’ cultures. He suggested that the surgery was conducted in order to allow evil spirits to escape from the cranium (Broca, 1876). It had been previously recognised that some cultures explained conditions such as epilepsy as being caused by trapped spirits, but Broca extended this idea to suggest that ancient cultures might also have explained any behavioural disturbance, including those that might be seen in mental illness, as being caused by spirits imprisoned within the cranium (Finger & Clower, 2003). One particular skull was very influential in convincing Broca of this explanation. The cranium in question had three elliptical shaped holes cut into it, and whilst one of these holes had been created during the early life of the individual, the other two had been created after death. Broca suggested that the significance of the pieces of skull which had been removed after death, was that they had a magical protective property and would have been used as amulets. Indeed, an amulet from another skull was found buried with the current specimen. Broca reasoned that the individual who was trepanned had some kind of affliction which was considered to be caused by the invasion of evil spirits in the body. They were then subjected to trepanation which led their affliction being cured as the evil spirits were allowed to escape through the hole made in the skull. Afterwards this individual was considered to be a significant one in their community because of their liberation from spirit possession. On their death, they had other pieces of skull removed to act as amulets to protect others within the community from spirit possession. In the words of Broca himself,

This suggestion had wider backing than just Broca (e.g. Fletcher, 1882; Bertillon, 1875; Wakefield & Dellinger, 1939), and in support of his proposal that skull sections from trepanned individuals were used as magical protection in the form of amulets, several pieces of skull were later discovered which were smooth as if polished by hand and had small holes bored in them which could have been used to thread string through for wearing (Gross, 1999).

Indeed, Bertillon (1875) suggested;

The belief that spirits or demons invade the body and cause illness or abnormal behaviour has been prevalent worldwide and has an extensive history (Norbeck, 1961). Spirit or demonic possession was not just considered a cause of unusual or bizarre behaviour which we might now consider psychopathological, but was considered a cause for all kinds of physical illnesses which were observable to the community. The following quotation from Norbeck (1961) illustrates this thinking and comes from a study of a rural Japanese community,

Indeed, Broca (1876) proposed;

In essence, any physical, behavioural, emotional or mental problem that could not be expla...