1

Introduction

Why do public and nonprofit professionals need to be culturally mindful communicators?

Communication challenge

Lavita’s case

Lavita enjoyed the morning drive into work, especially in spring, when she could breathe in the fragrant morning air through her rolled-down window. The neighborhood where she worked in Westlawn was growing. A building under construction along the way was now complete, and a sign in Spanish said a Hispanic grocery store was opening soon.

In response to the first, “How are you?” at work, Lavita exuded a little about the fine spring weather, and mentioned the new ethnic grocery store opening up the street. Lavita was paying attention. Her position as cultural inclusion coordinator at the City of Westlawn was created about a year ago to make the city’s operation more inclusive and equitable to all residents. She watched the demography. Westlawn had a population of 35,000, located on the outskirts of one of the major economic centers in the region. Historically it was a well-off lumber mill town, but those times faded rapidly just before the millennium. Instead, the city developed a high-tech industry park a decade ago as a new economic hub, and an influx of high-tech companies brought new types of jobs and new types of people, many of them from other parts of the country or from overseas.

Westlawn and the surrounding county also relied on long-rooted farming and orchard industries, which brought seasonal workers, especially during harvest. Many of the seasonal workers were Hispanic. Lavita herself was a second-generation Hispanic.1 Her parents came to the United States from Mexico when her mother entered medical school, and they stayed after she graduated. Lavita herself was born and raised in the United States. She eventually obtained a graduate degree in public affairs and policy, and worked a while as a researcher at the university – until she spotted the job ad for her current job at the City of Westlawn, when she decided to pursue her passion for community development and public service.

Returning to her desk with her morning coffee, Lavita ran into Bob, the city manager, pretty much as expected. Bob liked to meet with his direct staff informally at least once a week, as if they just happened to bump into each other. Lavita appreciated his regular attention to her projects, and his genuine interest in her observations and ideas on cultural diversity and inclusion at the city. Early on, at Bob’s suggestion, Lavita began working with Emily, the human resources director, mostly on an initiative to recruit and hire more people with diverse cultural backgrounds. This was the topic on her mind as she took a seat at the round table in Bob’s office. Tension was appearing among some of the employees.

Lavita shared the things she’d heard from employees who have been with the city, like:

“These folks can’t even speak English.”

“I can’t figure out whether they are nodding their head in agreement or shaking their head in disagreement.”

“They are always late.”

On the other side, a few of the recent hires from minority cultures approached her to express discomfort working at the city, due to a sense of animosity among the old-timers, and occasional comments with hostile undertones. It was obviously affecting their morale, and Lavita was concerned that the city would not be able to retain some of these recent hires unless something was done to make the work environment more inclusive.

Bob looked momentarily disturbed. “We need to do something about this, Lavita. Similar attitudes may be affecting our services and the city’s reputation, too.” He told her of two encounters he had at a recent Chamber of Commerce meeting: one with a Hispanic business owner, the other with a sales manager at a high-tech company. One mentioned a rumor about a hostile environment at City Hall for minority employees; the other reported a complaint from a minority colleague who was treated in a disrespectful manner trying to get service at City Hall.

“You and Emily, check this out, will you? And come up with a plan?”

Leo’s case

As a program officer for education programs at the Community Foundation, Leo was used to listening to presentations of ideas from grantees as well as colleagues around the office. As demographics in the local community changed, he noticed more projects addressed issues of social equity and inclusion.

“Thanks for coming to share your project update,” Leo said cordially to David and Aasiya from NewResident Support, as he stood up from the table in the foundation’s conference room. “This was very helpful.”

NewResident Support was a small nonprofit organization that provided assistance to immigrants. The organization had been in existence a couple of years, and succeeded partly through community grants. David was the founder and Aasiya was a long-time staff member.

At the exit, Leo shook hands with David. Aasiya, a Somali woman in a headscarf, nodded. She did not make a move to shake hands with Leo, and he noticed from her body language that she did not intend to. He drew his hand back.

Returning to his desk, Leo reflected on Aasiya’s reluctance to shake hands with him. Being a third-generation Japanese American, he remembered how his grandmother, a first‑generation Japanese immigrant, did not like shaking hands. She would shake hands hesitantly if she thought it would be rude or inappropriate not to, but she bowed at the same time. This experience helped him recognize Aasiya’s reluctance.

“Cultural differences can be unexpected,” he cautioned himself. He grabbed a post-it note when he reached his desk, leaned over and wrote on it in bold strokes, and pressed it on the lower corner of his computer monitor. It read:

“Be Mindful.”

Importance of culturally mindful communication skills for public and nonprofit administrators

During the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, public and nonprofit organizations in the United States – and in many other parts of the world – started to acknowledge the importance of cultural diversity in the workforce and in communities. As Michael Dukakis, the former governor of the commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the Democratic Party’s nominee for president of the United States in 1988, noted:

In this day and age, leadership, particularly in the public sector, must include both a deep respect for and a real understanding of the extraordinary and growing range of cultures and backgrounds that increasingly confront an American politician or policy maker.

(Dukakis, 2009, p. xi)

The need to develop intercultural understanding and effective communication has long been recognized among public administrators and nonprofit professionals in international contexts. Workers in international relations, diplomacy, intelligence, social agencies, and the military deal with national and cultural differences on a daily basis. Other global concerns, such as disaster relief, human rights advocacy, and environmental conservation also employ people from different countries who need to know how to communicate effectively across cultures. Their work may require traveling and living in foreign countries. Being culturally mindful is important for these, and many other, public and nonprofit professionals.

Dukakis was pointing out that the ability to function effectively in a diverse cultural context is becoming more important in a domestic context, too. Even in municipal governments or local nonprofit organizations, a variety of situations require attention to cultural diversity, as illustrated in the cases of Lavita and Leo introduced above. The following sections of this chapter discuss some of the background and reasons why it is important for public and nonprofit professionals to develop culturally mindful communication skills.

Cultural diversity in the community we serve

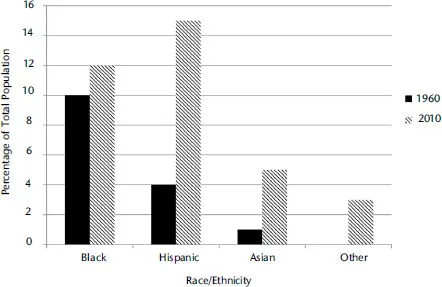

According to demographers, from 1960 to 2010, the percentage of persons who identified themselves as nonwhite (i.e., black, Hispanic, Asian, or other) increased from 15 percent to 36 percent of the population. Specifically, those who identified themselves as black increased from 10 percent to 12 percent; Hispanic from 4 percent to 15 percent; Asian from 1 percent to 5 percent; and “other” from 0 percent to 3 percent. By 2060, these percentages are expected to increase. The foreign-born population is projected to grow to nearly 20 percent of the total population. With the Hispanic population rising to 31 percent, the once dominant white population will drop to only 43 percent, making race-based minorities a majority (Colby & Ortman, 2015; Taylor, 2014).

The demographic changes illustrated above can be partially attributed to the forces of globalization. Globalization refers to the processes of international integration, and the increase in permeability of traditional territorial borders shaped by the interchange of both tangible and intangible factors, including goods, people, worldviews, ideas, and other aspects of culture (Choucri & Mistree, 2009). As the result of globalization, different countries, cultures, and organizations develop dense networks of interconnection and interdependency (Tomlinson, 1999).

Figure 1.1 Breakdown of non-white American: 1960, 2010

We have a long history of globalization, since humans started exploring and conquering new lands, trading goods, and spreading religions. The term globalization became popular in the 1970s (Osterhammel, 2005) as international networks expanded in both extent and intensity, in commerce and also in movements of people, ideas, and pollutants. Uneven growth and development within and across nations and regions has propelled cross-border movements that contributed to demographic and social transformations (Choucri & Mistree, 2009).

Since the 1970s, elements of cultural diversity began to reach the awareness of public and nonprofit professionals serving local communities. Exposed differences in racial and ethnic backgrounds, and differences in sexual orientation, physical ability, and socioeconomic status accelerated, posing new challenges.

The concept of social equity was explicitly stated as an important core value in public administration at the first Minnowbrook Conference, held in 1968 (Gooden, 2015). A widely used definition of social equity from the National Academy of Public Administration refers to it as:

fair, just, and equitable management of all institutions serving the public directly or by contract, and the fair, just, and equitable distribution of public services, and implementation of public policy, and the commitment to promote fairness, justice, and equity in the formation of public policy.

(Standing Panel on Social Equity in Governance, 2000)

Svara and Brunet (2005) argue that social equity needs to include the following commitments from public and nonprofit organizations: (a) procedural fairness, including due process, equal protection, and equal rights; (b) distributional equity, referring to equal access to services and benefits; (c) process equity, including equal quality of services; and (d) outcome equity, addressing equal impact of policies.

Cultural diversification in the communities we serve urges public and nonprofit professionals to develop communication skills with others of different backgrounds and cultural contexts to assure equitable service to all cultural groups, and more and more, work to heighten one’s own and the public’s awareness to be ...