eBook - ePub

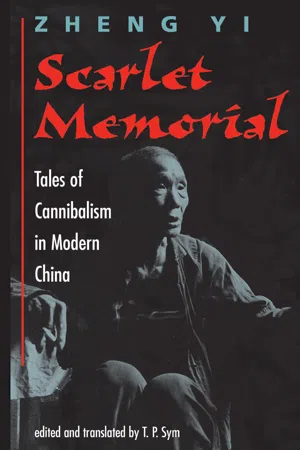

Scarlet Memorial

Tales Of Cannibalism In Modern China

Yi Zheng

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 223 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Scarlet Memorial

Tales Of Cannibalism In Modern China

Yi Zheng

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This book provides a meticulously documented account of officially sanctioned cannibalism in the south-western province of Guangxi during the Cultural Revolution. Zheng Yi paints a disturbing picture of official compliance in the systematic killing and cannibalization of individuals.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Scarlet Memorial als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Scarlet Memorial von Yi Zheng im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica asiatica. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

Searching Out the Criminal Evidence

Strike While the Iron is Hot

On May 17,1986,1 once again stepped onto Guangxi soil. Accompanying me was my literary friend, Bei Ming, who specializes in literary theory and has a fervent interest in cultural anthropology. She intended to learn about the carefree and romantic southern culture, for which she has great respect, and, of course, she would help me in my explorations to understand Guangxi. A longing of mine was finally to be realized; I was excited and yet at the same time I felt a sense of absurdity. How dramatic—here we were, on a fine sunny day in the 1980s, at the end of the twentieth century, planning to investigate the occurrence of cannibalism. The Thousand and One Nights! The tragedy had already been verified, but the beautiful sunshine of southern China made me feel like a jaded cynic, a victim of neurosis.

Since this was our first trip to Nanning, the capital of Guangxi, Bei Ming and I were total strangers. We hailed a three-wheeled pedicab and decided to look for a place for Bei Ming to stay. I had no such concerns for myself, since I had already presented the local authorities with an official letter of introduction that was supposed to provide me with an official residence. The pedicab was very reasonable and the driver was very friendly. When he saw that we weren't satisfied with the hotel that he had recommended, our driver offered to help us look for another place. Somewhat afraid that he might be trying to cheat us out of money—such was the typical reaction of people from hard-edged cities like Beijing—we politely turned him down and began to search on our own. But as we walked along the streets the driver followed us and from time to time offered his counsel, all for free. It seemed that he was not interested in our scant supply of money, but somehow we could not relax. The ancient saying, "Measuring the gentleman's mind with a petty man's heart," well describes our attitude. It was indeed embarrassing. He was the first Nanning local we encountered.

The public transportation system in Nanning also left a deep impression on both of us. Passengers got on and off the bus in two distinct, orderly lines through a narrow door. This was not at all like the crazy, maddening scene in other big, crowded cities. One rainy day, when we were on our way to an interview, we noticed that all the bicycles lined along the streets were covered with the raincoats of their owners: red, blue, and green. Such a scene was rarely seen in other places. On the narrow paths in the villages, Zhuang women of the local minority nationality, especially the young women, politely stopped at a distance as we approached to let us pass by.* This modest and courteous tradition made us almost feel that we were in a kind of wonderland. We were so moved that we even thought that perhaps the slaughter and cannibalism during the Cultural Revolution were nothing more than rumors. Maybe they were part of some historical myth that never could be resolved.

Once Bei Ming settled down, I went to look for a local reporter for the China Legal News (Zhongguo fazhi bao) named Wei Huaren, who had been recommended to me by friends in Beijing.† Little Wei, as he was known, was a Guangxi local. In a rather authoritative manner he immediately confirmed the dire rumors about cannibalism. As soon as he had reserved a room for me in the local Public Security Bureau guest house, Little Wei immediately arranged a meeting between myself and Wang Guanyu, deputy Party secretary of the Political and Legal Committee of the Guangxi Autonomous Region. Then, on the afternoon of May 19, he accompanied me to Wang's office. I produced my journalist's credentials, the letter of introduction from the central offices of the China Legal News under the central Ministry of Justice, plus an additional letter of introduction from the All-China Writers' Association. I also explained the purpose of our trip, just as I had discussed it with Bei Ming in advance: I intended to collect historical materials on various ruthless incidents during the Cultural Revolution and to analyze the poisonous effects of ultra leftism from a psychological perspective.‡ Although it was true that the psychological perspective could not be ignored, I intentionally couched my plan in somewhat casual terms so that I would not arouse any suspicions. The Chinese Communist Party has always been sensitive about its mistakes, and it is especially fearful that writers or journalists might uncover some buried truths.* Cover-ups and distortions had become standard operating procedure among cadres at various levels.

My official status and the introduction by Little Wei allowed me to present my main topic to Wang without difficulty. As soon as I mentioned the Cultural Revolution in Guangxi, his anger burst forth. He picked up a document from his table, slapped it down, and declared that the head of a certain county's People's Armed Police who had initiated the slaughter of numerous people had been given the relatively light sentence of suspended capital punishment. The document, which I quote from later, notes that the sentence had been based on the fact that the suspect had killed more than fifty people but that a more recent investigation had proved that the total number of victims was only twenty-six; the criminal had therefore requested a retrial. As he told me this, Wang Guanyu didn't know whether to laugh or cry. "The Central Committee insists time and again that historical issues should be handled in a lax manner, ignoring the details.+ As for leftover cases from the Cultural Revolution in Guangxi," Wang added, "those who should have been sentenced to death were allowed to live, and those who deserved stiff sentences went free. It could not have been more forgiving. Of course, the more generous you are, the sorrier they feel for themselves! Ninety thousand innocent victims were slaughtered, while only a dozen criminals received capital punishment. Even though this guy killed twenty-six, rather than fifty, this murderer has the gall to claim that he is being treated unfairly! What kind of reasoning is that? No way!"

Secretary Wang seemed like an honest person, with no blood on his hands. At the end of our conversation, he signed my letter of introduction: "To the Party Reform Office of the Guangxi Autonomous Region: Please take care of all matters involving the work of this journalist." Wang let me in on the information that the Party Reform Office was actually the former work team that cleared up leftover cases from the Cultural Revolution. Upon leaving his office, I was ecstatic. How fortunate I had been to get so much information from the senior cadre in charge of legal affairs. Even more important was that I had been given a green light to conduct interviews throughout the entire Guangxi region.

Strike while the iron is hot! I immediately asked Little Wei to accompany me to the Party Reform Office, where I was initially welcomed by Huang Xiangheng and Huang Shaobin. Later, I was directed to talk with Comrade Yu Yaqin of the group handling and verifying leftover cases (chuyi keshizu). I now had the holy sword of the political and legal committee of the autonomous region in hand. Equipped with this weapon, I had the courage I needed to bring up the incidents of slaughter and cannibalism that had taken place during the Cultural Revolution. Unassisted by notes, in one breath Yu described quite a few famous cases and mentioned the following counties: Wuxuan, Rongan, Binyang, Shanglin, Zhongshan, and others. Yu also advised me that in order to investigate these incredibly cruel cases thoroughly, I would have to go to Wuxuan County.

Now that the events friends had told me about had been verified by local officials, I immediately proposed that I conduct a series of interviews in counties located in the Nanning, Wuzhou, and Liuzhou Prefectures where some of the most intense factional fighting and barbarism had occurred during the Cultural Revolution. And because this plan accorded with the official clearances I had been given, the various cadres of the Party Reform Office added their signatures, below that of Secretary Wang Guanyu, with instructions addressed to the Party reform offices in Nanning, Wuzhou, and Liuzhou to "please make all the necessary arrangements for interviews by this journalist." I had passed, yet again, a major obstacle. Although I could have obtained most of the information by reading relevant Party documents and materials in official files and archives, I knew that in China, the higher the bureaucrat, the tighter his mouth. I believed, therefore, that it would be more fruitful to focus on the local level, on the counties, towns, and villages, assisted by official signatures, and telephone instructions from higher-ups whom the locals would not dare to challenge. I would be able to get my hands on the original documents and sift out evidence in a completely legal way. In addition, I would be able to meet with various types of people and get firsthand material and information. And, of course, I would also be able to learn more about local history, traditions, and customs. Although this method surrendered the near for the distant, it later proved to be the only effective way for me to break through the various obstacles, bureaucratic and otherwise, to obtain the most important and reliable information.

On day two, I showed up at the headquarters of the Prefecture Party Committee of Nanning; Deputy Secretary-in-Chief Li contacted the authorities in Binyang and Shanglin Counties to set up the interviews.

As a reporter for the only major newspaper in China that serves the legal profession, Wei Huaren would have been more than willing to accompany me during the interviews, but he was preoccupied with work at his own newspaper and simply couldn't find the time. As we parted, he warned me once more to heed my personal safety and never to act on my own. Wei also advised me that when I traveled to the scenes of earlier crimes, I should always make sure to register with the local authorities first and always conduct my interviews in the presence of a local official.

My investigation and interviewing was to begin in Binyang County where, it was said, cannibalism had been widespread. Word had it that the residents, long experienced as they were in the business of eating people, had concluded that outsiders were tastier than locals. Consequently, it was said that they would first drug the unsuspecting traveler into a stupor and then start cutting and consuming. When the effects of the drug began to wear off, they would hold a mirror to the victim's face and force him to watch while his own body was being consumed. This seemed too bizarre. (In fact, such events never came to light in any of my later interviews; perhaps it had been merely a rumor after all.) Upon discussing this possibility with Little Wei and considering his warning to me, I was in the mood for a bit of comic relief. "Isn't it true that no writer has ever been consumed before in Chinese history?" I asked him. Neither of us could help but laugh.

The next morning I took off for Binyang by myself. Bei Ming returned home. Since my name alone appeared on the letters of introduction, her presence possibly could have caused some unexpected trouble. Heavy rain the night before brought a cooling freshness to the air. The green fields along my route were extremely refreshing to the eye. At about "10 A.M. I arrived at the town of Luxu, the site of the county seat, and later that afternoon I met with Li Zengming, the Party secretary of the local Party Discipline Inspection Commission, the CCP's internal disciplinary organ. At the very mention of the killing that had occurred in Binyang, the secretary became outraged. Before I could even ask him specific questions, he provided the most vivid and explicit description of the collective act of slaughter. His description pretty much coincided with the following account, taken from a post-Cultural Revolution edition of the Binyang County Gazette:

At the end of July 1968, Wang Jianxun, director of the county Revolutionary Committee (and concurrent deputy division commander of the 6949 Unit), and Wang Guizeng, deputy director of the same committee (also deputy political commissar of the County Armed Police), in the name of executing the "July 3 Bulletin," mobilized vicious assaults on so-called class enemies. Total dead and injured came to 3,883 people. Together with the sixty-eight people who had been beaten to death before the July 3 Bulletin, the total number of casualties came to 3,951—a great act of injustice.1

Just what was the "July 3 Bulletin"? After I was on the run in 1989 after the June 4 Beijing massacre, I was unable to obtain the original document. But as someone who had lived through the Cultural Revolution, I could still remember its general gist. Issued jointly by the Central Committee, the State Council, the Central Military Commission, and the Central Cultural Revolution Group controlled by Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, this document had whipped up a frenzy of killing and carnage. According to the original declaration, Liuzhou, Guilin, and Nanning in the Guangxi Autonomous Region had purportedly suffered widespread disruption of railway communication, robberies of weapons caches bound for Vietnam, and outright attacks on PLA units, among other things. As a reaction to these events, the bulletin called for tougher measures to be taken against all class enemies. Although it contained no explicit reference to indiscriminate killing (gesha loiilun), the entire document was suffused with an air of killing and vengeance.

Soon after the "July 3 Bulletin" was issued, the Binyang County Revolutionary Committee held a mass rally of 7,000 people under the banner of "Marching in the Name of 'Loyalty' by All the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants in the County" At about the same time, the national campaign to create a god was inaugurated, in which everyone "asked for instructions in the morning and reported back in the evening," engaged in "loyalty dances," and promoted the "three loyalties and four devotions." With the erection of the statue of a god, Mao Zedong by name, wholesale slaughter could then be carried out. The history of China at this time is replete with such cases, and border regions like Guangxi were no exception.

On July 22,1968, a telephone conference was held by the county Revolutionary Committee in which instructions went out to fully implement the "July 3 Bulletin."

Then, on July 23, a rally of "10,000 people was held by Wang Jianxun, the director of the county Revolutionary Committee, who gave a mobilizing speech. Yu XX, the deputy director, also gave a speech, in which he proclaimed that the "July 3 Bulletin" was part of Chairman Mao's ingenious strategy and the most powerful weapon for carrying out attacks on the small handful of class enemies.

On July 24, the "Leading Group for Executing the 'July 3 Bulletin' in Binyang" was established. It was composed of four leaders, all military men.2 The potential for killing was now set up. Within three days, all the arrangements had been put into place for carrying out a mad slaughter throughout the entire county.

July 25.

Not a flag or drum was to be found anywhere—it was the silence before the slaughter.

July 26.

The Military Control Commission of the public security organs of Binyang County held a meeting and issued the order to all local Party committees, public security personnel, and to local public security precincts at the district and township levels to commence the killing. On the same evening, the Revolutionary Committee of Xinbin Township held a mass dictatorship rally, in the course of which two people were beaten to death on the spot. The bloodshed had begun.

July 27.

Market day in Xinbin Township. Fourteen people were labeled "four elements social dregs" (sileifenzi),* subjected to street criticism parades, and then beaten to death. The practice was thus launched to kill select groups of people all at one time.

The same day.

The local office of the armed police of Binyang County ordered cadres to visit the sites where these killings had taken place. At the same time, the comman...