eBook - ePub

The Holocaust

Roots, History, and Aftermath

David M. Crowe

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 542 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The Holocaust

Roots, History, and Aftermath

David M. Crowe

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This book details the history of the Jews, their two-millennia-old struggle with a larger Christian world, and the historical anti-Semitism that created the environment that helped pave the way for the Holocaust. It helps students develop the interpretative skills in the fields of history and law.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The Holocaust als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The Holocaust von David M. Crowe im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Jewish History

Ancient Beginnings and the Evolution of Christian Anti-Judaic Prejudice Through the Reformation

CHRONOLOGY

—Second Millenium B.C.E. (Before the Common Era): Abraham receives covenant from Hebrew God YHWH

—Thirteenth Century B.C.E.: Moses leads Hebrews on Exodus and receives Ten Commandments

—1025–926/925 B.C.E.: Israel created by Sol, David, Solomon

—966–926/925 B.C.E.: Solomon builds Temple in Jerusalem for Ark of Covenant

—722–586 B.C.E.: Israel conquered by Assyrians and Chaldeans

—586 B.C.E.: Nebuchadnezzar destroys Jerusalem and Temple; Babylonian Captivity begins

—586–200 B.C.E.: Jewish Bible, Tanakh, completed

—164–64 B.C.E.: Maccabean rebellion leads to recreation of Israeli state

—64 B.C.E.: Pompey conquers Palestine for Rome

—37–4 B.C.E.: Herod the Great rebuilds Jerusalem and Second Temple

—6–4 B.C.E.: Birth of Jesus (Joshua) of Nazareth

—66–70 C.E. (Common Era): Jewish War and the Great Revolt leads to Roman destruction of Second Temple

—73 C.E.: Masada falls to Romans

—70–100 C.E.: Christian Gospels written

—132–135 C.E.: Bar Kochba rebellion

—312–337 C.E.: Reign of Constantine the Great

—325 C.E.: Council of Nicaea

—354–430 C.E.: St. Augustine. Wrote City of God and Tractus adversus judaeos

—476 C.E.: Traditional date for collapse of Western Roman Empire

—527–565: Reign of Byzantine (Eastern Roman) emperor Justinian I. Corpus Iuris Civilis

—768–814: Charlemagne

—1095–1099: First Crusade and Christian conquest of Jerusalem

—1147–1149: Second Crusade

—1187–1192: Third Crusade

—1135–1204: Moses Maimonides

—1141: Jews accused of “ritual murder” in Norwich, England

—1198–1216: Reign of Innocent III

—1202–1204: Fourth Crusade

—1290: Edward I expels Jews from England

—1306: Jews expelled from France by Philip IV

—1347–1351: Black Death

—1492: Ferdinand and Isabella expel Jews from Spain

—1517: Martin Luther writes his Ninety-five Theses

—1543: Luther writes On the Jews and Their Lies and On Schem Hemphoras and the Lineage of Christ

—1484–1531: Life of Protestant reformer Ulrich Zwingli

—1508–1564: Life of Protestant reformer John Calvin

—1553: Pope Julius III orders Italian Jews to live in ghettos

In the introduction to his The Gift of the Jews, Thomas Cahill says that the Jews were the creators of Western culture. Whether or not one agrees with this assertion, the fact remains that the Jewish people, their religion, Judaism, and Jewish culture and history have deeply affected Western civilization. For non-Jews in particular, studying the Holocaust is usually the only contact they have with Jewish history. To avoid seeing Jews only in light of their Holocaust victimization, and to understand the rich dynamics of the Jewish past before not only the Holocaust but also during the two millenia of anti-Jewish and anti-Semitic discrimination and hatred that preceded it, it is important to see the Jews in a broader historical perspective. Embedded in this history are not only the rich stories and contributions so important to Jewish and Christian history but also examples of Jewish determination to maintain and defend their beliefs no matter what the cost. The deep commitment Jews have to their faith traditions, their culture, and their history has made them unique in Western culture. During the Holocaust, the Germans and their collaborators did everything possible to mass murder the Jews of Europe and to destroy their ancient religious, cultural, and historic traditions.

Jewish Beginnings

The history of the Jews, or as they were known in ancient times, the Hebrews, began almost 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia. As members of the Semitic subfamily of languages that included Arabic, Ethiopic (Amharic), Phoenician, and Aramaic, the Hebrews traced their historical-spiritual roots to Abraham, the father, or patriarch, of the Hebrew people. Jewish tradition says that Abraham received a covenant from the new Hebrew god, YHWH, that would give the Hebrews, in return for their worship of YHWH alone, a promised land in Canaan. This faith and covenant formed one of the cornerstones of the early Hebrew faith. In the Jewish scriptures, various names have been used for the name of God that describe God’s various characteristics, including El, Elohim, and Adonai. In the Middle Ages, Christian scholars “transformed the word YHWH with the vowelization for the word ‘Adonai’ into Jehovah.”1

Abraham passed on his covenant with God to his son, Isaac, and then to his grandson, Jacob or Israel, and his descendants. The twelve tribes of the ancient Hebrews or Israelites were named after Jacob’s sons. The tribe of Jacob’s fourth son, Judah, would come to play a dominant role among the Hebrews, and would provide the name for the Hebrew religion, Judaism. Historically, Jews, believers in the religion of Judaism, considered themselves descended from the House of Jacob and called themselves the Children of Israel.

The early Hebrews were semi-nomads who spent considerable time in Egypt. Though originally a land of opportunity and prosperity, Egypt became a place of oppression and mistreatment, particularly after Pharoah Rameses II (r. 1301/1298–1234/1232 B.C.E.) enslaved the Hebrews. Over time, the Hebrew population became so large that, to reduce it, Rameses II ordered the murder of every Jewish male child. Moses’s mother set him adrift in a reed basket to save him. Rameses II’s daughter found him and adopted him. Later, when Moses learned about his roots and the mistreatment of his people, he fled into the desert; there, God told him that he had been chosen to lead his people out of bondage. Soon, Moses demanded that Rameses II’s son, Pharoah Merneptah (r. 1232–1224 B.C.E.), emancipate the Hebrews. After several plagues had swept through his kingdom, Merneptah agreed. What followed was the Exodus, one of the most seminal events in Jewish history.

The Exodus transformed the Hebrew people through a new covenant inscribed by YHWH on the Tablets of the Covenant (Ten Commandments). Later housed in the Ark of the Covenant, the Ten Commandments, revered by both Christians and Jews, are the cornerstone of Jewish belief and practice. Moses emerged from this dramatic exodus as the creative center of the Jewish national concept and the central figure in the Hebrews’ historic faith—Judaism. Jewish ethical monotheism, anchored by the Law of Moses, emerged during Moses’s time; Jewish scholars later recorded the Law of Moses in the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanach), or, to Christians, the Old Testament. At its core were 613 commandments, which the brilliant Jewish scholar Maimonides (1135–1204) divided into 248 positive and 365 negative commandments. At the heart of this faith system was the link between ritual and worship on the one hand and ethics on the other within the Hebrew, and later, Jewish traditions. The basic Jewish statement of faith, the Sh’ma, is in Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear, O Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord alone.”2

The uniqueness of Hebrew or Jewish monotheism did little to give this small group of people easy access to their promised homeland or bestow nationhood upon them. An independent Jewish state evolved under the kingships of Saul (r. 1025–1005 B.C.E.), David (r. 1005–966 B.C.E.), and Solomon (r. c. 966–926/925 B.C.E.), driven in part by the need for a centralized military command vis-à-vis outside threats to Jewish political and territorial autonomy. David captured Jerusalem from the Philistines; his son, Solomon, fulfilled David’s dream of building a Temple to house the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the Ten Commandments. He also completed David’s construction of Jerusalem. Because they represented Jews’ special relationship with their God, the Temple and Jerusalem have been important symbols to Jews throughout history.

During this time many of the great Hebrew prophets emerged and served as intermediaries between God and His people. As the Hebrew people struggled to develop a state, the prophets reminded them of the importance of God in their lives and society. The largest section of the Hebrew bible, the Tanakh, is the Nevi’im, which contains twenty-one books of the Prophets, beginning with Joshua and ending with Malachi. The prophets counseled the Jewish people on the importance of obeying God’s commandments and warned them of impending doom if they did not.

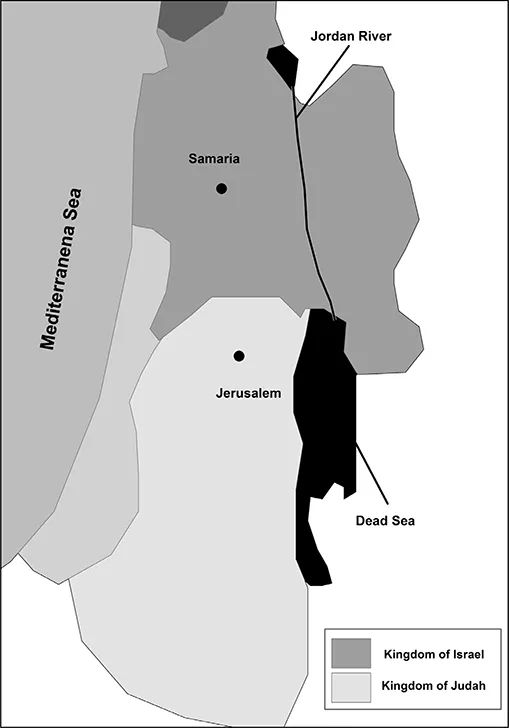

Two separate Jewish states emerged after Solomon’s death: the Kingdom of Israel in the north, its capital in Samaria; and the Kingdom of Judah (Judea) in the south, Jerusalem being its political and spiritual center. This division weakened the ability of the Jews to resist new outside threats. Amos and Jeremiah, two of the era’s great prophets, warned the Jews of the implications of their drift away from their spiritual and historic traditions. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered the Kingdom of Israel; a century and a half later, the Chaldeans (neo-Babylonians) under Nebuchadnezzar (r. 605–562 B.C.E.) destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple in 586 B.C.E. Afterwards, he forced the Jews into a Babylonian Captivity that would forever change Jewish history.

The Wailing Wall, Jerusalem. Photo courtesy of David M. Crowe.

Exile and New Traditions of Faith

A less remarkable people would have declined, and possibly disappeared, after the loss of their precious Temple and capital. Though traumatized by this tragedy, the Jews adapted to their circumstances while remaining stubbornly faithful to their religion and culture.

Since the Chaldeans did not enslave those Jews brought to Babylon, many Jews adapted to their new surroundings and found new roles in Chaldean society. More important, the Babylonian Captivity forced Jews to reevaluate their faith: they were determined to preserve their laws and traditions, which took on new importance not only for the priestly caste but also for the average believer. Though the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 B.C.E.), who conquered Palestine in 539 B.C.E., allowed Jews to return to their homeland and ordered the construction of a new, Second Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, many Jews continued to live elsewhere in the Middle East. During this period, Jewish scholars completed the Jewish Bible, the Tanakh, in much the form as we know it today. They carefully recorded and divided these select Jewish writings into three major divisions: the Torah, or the Books of Moses; the Nevi’im, or the major and minor prophetic texts; and the Kethuvim, or Sacred Writings or wisdom books that included works such as the Psalms and Proverbs. The name Tanakh comes from the initial letters of these three scriptural divisions. Between 400 and 200 B.C.E., the Torah and the Nevi’im acquired canon or divine status, but the Kethuvim would not be fully recognized as part of the Jewish scriptural tradition until the end of the first century of the Common or Christian Era (C.E., or Christian A.D. [Anno Domini, “in the year of our Lord”]). Some of these books would later be included in the Christian Old Testament. This process transformed Judaism, which now became rich in historical, literary, and religious traditions unique to the ancient Mediterranean world.

Ancient Israel.

The Jews, Hellenism, and the Maccabean (Hasmonean) Rebellion

The Jewish diaspora that had begun with the Babylonian Captivity forced the Jews to deal with a much broader complexity of rulers and peoples than they had heretofore encountered. This process intensified after the Macedonian-Greek Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 B.C.E.) conquered Palestine. Now the Jews had to deal with Hellenistic Greek history, culture, and religious traditions so powerful that they dramatically transformed not only the Jews and Judaism but also Western civilization.

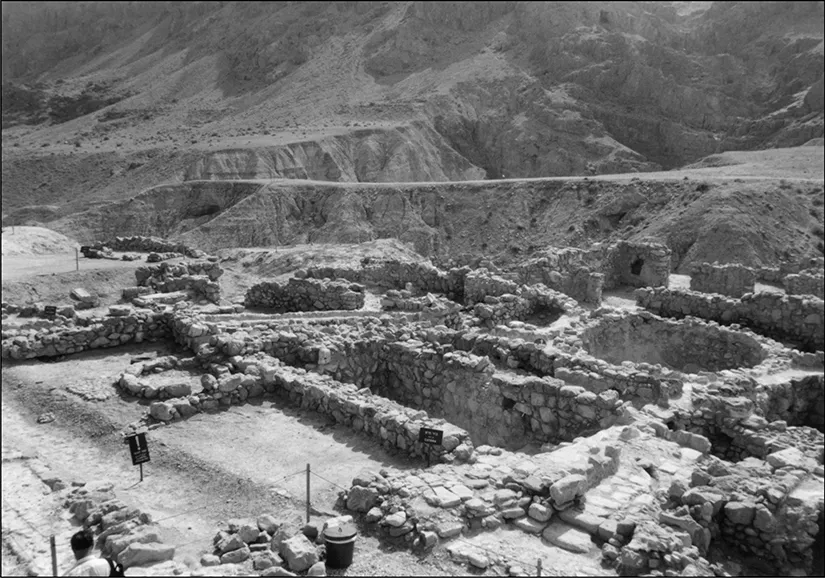

Judaism on the eve of the campaigns of Alexander the Great was a vibrant cultural-religious force in Judea, Samaria, and beyond. The large, steady wave of Greek settlers that moved into Palestine in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. deeply troubled some Jews. One group, the Essenes, who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, tried to recapture their Mosaic past in isolated desert communities. However, a far greater number of Jews embraced many linguistic and cultural aspects of Hellenism. Wealthier Jews also saw in Hellenism a way to greater status, acceptance, and influence. A small group of Hellenizing Jews even tried to rid contemporary Judaism of many traditional practices: They wanted to blend the ethical monotheistic essence of Judaism with a universal Greek civilization.

The growing influence of Hellenistic culture was felt most harshly after the Seleucid (the post–Alexander the Great successor state in Persia, Syria, and Asia Minor) conquest of Palestine in the late third century B.C.E. In 167 B.C.E., the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–163 B.C.E.) replaced the Law of Moses with Seleucid Greek law and transformed the Temple into a place of worship for Greek and Hebrew gods. In response, Judas the Maccabee led a Jewish guerilla war that successfully drove the Selucids out of Jerusalem and, in December 164 B.C.E., restored the Second Temple. Hanukkah (“Dedication”), the eight-day Jewish holiday, celebrates the Maccabean victory and the restoration of Jewish control over the Second Temple. During the next twenty years, the Maccabean, or Hasmonite, Jewish dynasty acquired virtual independence from Seleucid control by allying with Rome. According to Menahem Stern, the significance of the Maccabean Revolt was that “Judaism had never been in such danger of complete extinction” as it had under Antiochus IV.3 The Maccabean Revolt was a rebellion of Jewish survival.

Qumran. Photo courtesy of David M. Crowe.

Hasmonean Israel and Rome

For the next seventy-nine years, Hasmonean Israel, wedged as it was between a declining Seleucid state and the growing Roman Empire, dramatically expanded its frontiers. The revolutionary spiritual zeal and rigid adherence to Mosaic Law that had neutralized the Seleucid rulers remained a driving force in the new kingdom. The principal advocates and defenders of this return to the traditions of the Mosaic codes were the Sadducees, a religious-political sect who were close allies of the Hasmonean rulers and the Jewish state’s upper classes. Their main political and religious opponents, the Pharisees,...