eBook - ePub

Understanding Architecture

Its Elements, History, and Meaning

Leland M. Roth

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 816 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Understanding Architecture

Its Elements, History, and Meaning

Leland M. Roth

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This widely acclaimed, beautifully illustrated survey of Western architecture is now fully revised throughout, including essays on non-Western traditions. The expanded book vividly examines the structure, function, history, and meaning of architecture in ways that are both accessible and engaging.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Understanding Architecture als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Understanding Architecture von Leland M. Roth im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Architecture & Architecture General. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

The Elements of Architecture

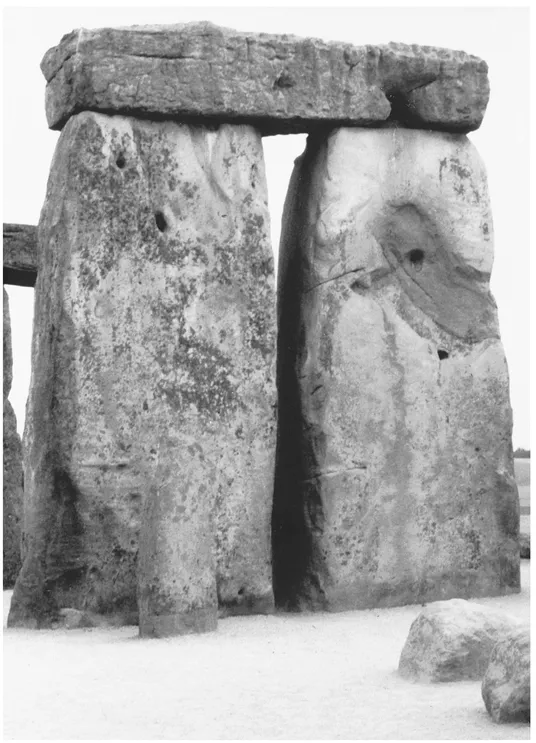

Stonehenge, 2600–2400 BCE. Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, England. One of the trilithons (“three stones”), with uprights standing 13 feet high, emblematic of the essence of architectural construction. Photo courtesy of Marian Card Donnelly.

Chapter 1

Architecture

The Art of Shaping of Space

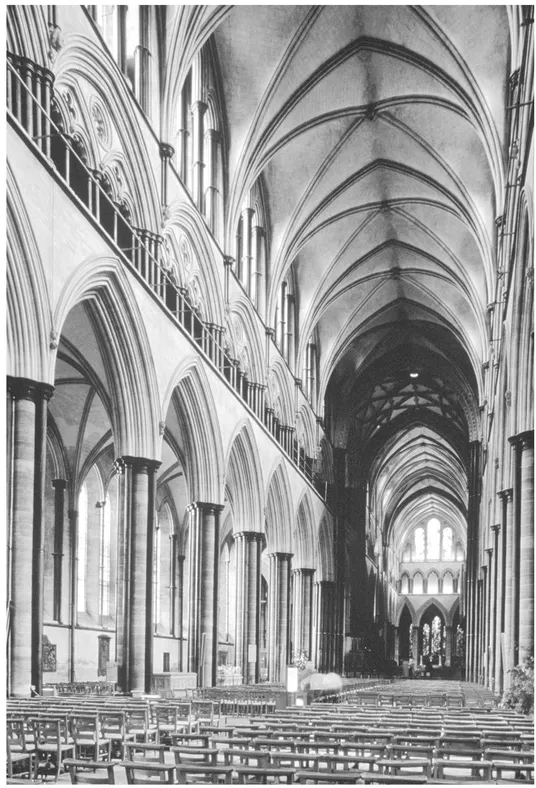

1.12. Salisbury Cathedral nave, Salisbury, England, 1220–1266, Interior, nave. The repeated bays and strong horizontal layering draw the eye strongly along the axis, illustrating directional space. Photo: Anthony Scibilia/Art Resource, NY.

The history of architecture is primarily a history of man shaping space.

—Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture, 1943

Today, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, digital artists can create a virtual image of the inside of a building. This is a most useful operation, suggesting what a building will be like long before costly construction is begun. But the total physiological, kinesthetic, sensory, and psychological experience is missing. Architecture must be experienced by walking around and into it.1

Architecture is the art into which we walk, the art that envelops us. Besides making a distinction between “architecture” and “building”—a concept with which there might be disagreement— Nikolaus Pevsner’s further observation that architecture is the shaping of space is undisputed.2 As he notes, painters and sculptors affect our senses by creating changes in patterns, and in proportional relationships between shapes, through the manipulation of light and color, but only architects shape the space in which we live and through which we move. Frank Lloyd Wright believed space was the essence of architecture and, early in his career, discovered that the same idea had been expressed centuries earlier by Laozi (Lao-Tse) and paraphrased in 1906 by Okakura Kakuzo in The Book of Tea. The reality of architecture, Kakuzo observed, lay not in the solid elements that seem to make it but in the empty space defined by those elements: “The reality of a room, for instance, was to be found in the vacant space enclosed by the roof and walls, not in the roof and walls themselves. In just the same way, the usefulness of a water pitcher dwelt in the emptiness where the water might be put, not in the form of the pitcher or the material out of which it was made.”3

The architect manipulates space of many kinds in many ways. There is first the purely physical space, which can be imagined as the volume of air bounded by the walls, floor, and ceiling of a room. This can be easily computed and expressed as so many cubic feet or cubic meters. But there also is perceptual space—the space that can be perceived or seen. Especially in a building with walls of glass, this perceptual space may extend well beyond the boundary of the glass and may be impossible to quantify. Related to perceptual space is conceptual space, which can be defined as the mental map we carry around in our heads, the plan stored in our memory. We navigate through our house, workplace, or community by referring to our mental map of its conceptual space. Buildings that work well are those whose plans and spatial arrangements can be easily grasped and held by users in their mind’s eye and through which they can move about easily with a kind of inevitability; such buildings can be said to have clear conceptual space. The architect can also decisively shape behavioral space, or the space we actually move through and use. Behavioral space can be imagined as a clearly defined room with four walls, a ceiling, and a floor—an easily calculated volume. But now picture a large hole that has been cut into the floor, with the opening covered by a cloth. The physical space has not changed at all, but a person now must walk around the periphery of the room instead of diagonally across it. The behavioral space has been changed.

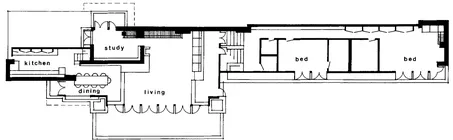

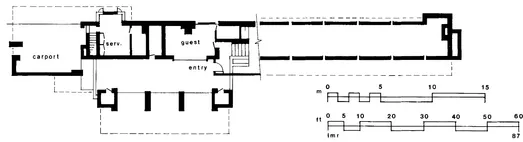

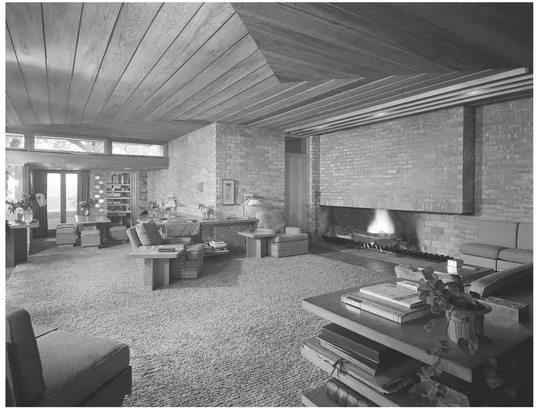

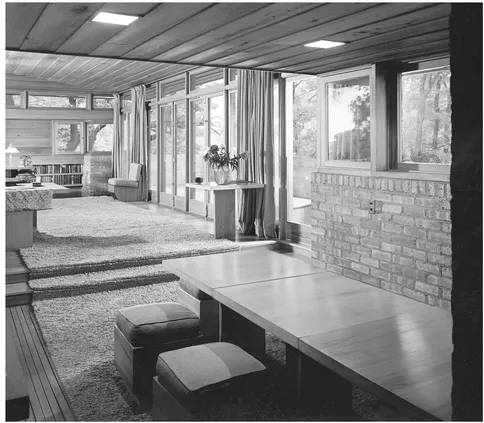

All the types of space just mentioned can be illustrated by examining the Lloyd Lewis House in Libertyville, Illinois, 1939, by Frank Lloyd Wright [1.1]. From within the living room, as we look toward the fireplace, the view is defined by the built-in bookcases, the brick of the fireplace mass, the floor, and the ceiling [1.2]. All the surfaces are opaque and suggest a clear sensation of confinement and protection; the physical space is evident. As we look left, however, the view stretches out through a

1.1. Frank Lloyd Wright, Lloyd Lewis House, Libertyville, Illinois, 1939. Plans of the lower level and the upper living level. Drawing: L. M. Roth.

1.2. Lloyd Lewis House. View of the living room, looking toward the fireplace; from this vantage point, the space is sharply defined and suggests comforting enclosure. Photo by Hedrich Blessing. Chicago History Museum, negative HB-19240-C.

1.3. Lloyd Lewis House. View of the living room, looking toward the screen of French doors; from this direction, a person’s view can pass into the countryside, into a large perceptual space. Photo by Hedrich Blessing. Chicago History Museum, negative HB-06485I.

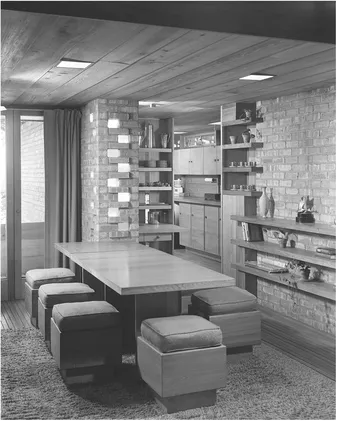

broad bank of glazed French doors to the meadow and woodland beyond [1.3]. From this vantage point, the perceptual space reaches out across the field and to the sky, as far as the eye can see. Moving toward the dining area, we see the built-in dining table, fastened to a brick pier [1.4]. To move from the living room through the dining area and into the kitchen, we must move around that built-in table, since it cannot be moved. In purely physical terms, the table takes up very little volume, a very few cubic feet compared to the many hundreds of cubic feet in the combined living and dining space, but in behavioral terms, it determines in a decisive way how we can move about in that space.

Architectural space, in all its various forms, is a powerful determinant of behavior. Winston Churchill understood this well when he addressed the House of Commons in 1943, noting that first “we shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”4 What prompted his observation was a debate on rebuilding the severely burned House of Commons. The chamber in which the Commons had been meeting for nearly a century was gutted by a German bomb in 1941, and Parliament was considering alternative ways of reconstructing the chamber. When Parliament had first begun to meet in the thirteenth century, it had been given the use of rooms in medieval Westminster Palace and had occupied the palace chapel. A typical Gothic chapel, it was narrow and tall, with parallel rows of choir stalls facing each other on either side of an aisle down the center. The members of Parliament sat in the choir stalls, dividing themselves into two groups: on one side the government in power and on the other the loyal opposition. Seldom did members take the brave step of crossing the aisle to change, and hence visibly declare, their new political allegiance. When the Houses of Parliament had to be rebuilt after the catastrophic fire of 1834, the old Gothic archetype had been followed, and Churchill argued that this ought to be done again in 1943. There were those who advocated rebuilding the House with a fan of seats in a broad semicircle, as used in legislative chambers in the United States and France. But Churchill convincingly argued that the essence of English parliamentary procedure had been permanently shaped by the physical environment in which it had first been housed: to so fundamentally change that environment, to give it a different behavioral space, would be to change the very nature of parliamentary discourse and government. The English had first shaped their architecture, he said, and that architecture in turn had shaped English government and history. Through Churchill’s persuasion, the Houses of Parliament were rebuilt with the old arrangement of parallel seats looking across a central aisle [1.5].

1.4. Lloyd Lewis House. View of the dining area, showing the built-in table; the fixed table clearly determines how a person is directed through this space, thereby determining behavior. Photo by Hedrich Blessing. Chicago History Museum, negative HB-06485i.

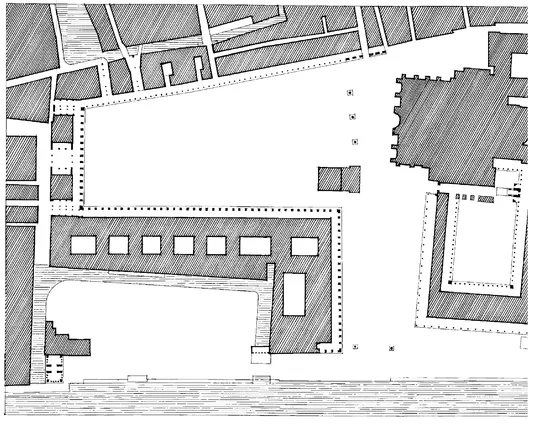

These concepts of physical, perceptual, and behavioral space have been applied here to spaces within individual buildings. With slight redefining, such terms can be used to describe experiences in large outdoor spaces as well. Consider the huge outdoor living room in Venice—the Piazza di San Marco [1.6, 1.7]. From the middle of the piazza as one looks west, the space is clearly defined and enclosed by the walls of the buildings on either side and straight ahead. Much the same is true if one turns around and faces east, toward the Church of San Marco, but with this perspective the light coming from the right gives a hint of an opening. Moving eastward, approaching the front of the church, one must move around the soaring tower of the Campanile, which stands in the piazza and determines one’s walking behavior. Once around the Campanile, one sees the smaller piazzetta, which extends toward the south. Past the pair of freestanding columns that mark the boundary of the piazzetta, one’s view crosses the canal, and the enclosed physical space opens up in a virtually boundless perceptual space.

The plan of the Lloyd Lewis House also illustrates clearly the possibility of fluidity of space— interwoven spaces as contrasted with static spaces. Wright was a master of interweaving connected spaces, creating what has been described as fluid or flowing spaces, beginning in his Prairie Houses of 1900 to 1910 and continuing in Fallingwater, near Mill Run, Pennsylvania, built for the Kaufmann family in 1936–1938 [1.8]. In these houses, there is no isolation of the living and dining rooms or the library alcove; all are loosely defined as component areas of a larger fluid space. Wright developed this

1.5. Sir Charles Barry and A. W. N. Pugin, House of Commons chamber, Houses of Parliament, London, England, 1836–1870; restored 1946. Following extensive damage after being hit by a German bomb, the House of Commons chamber, an example of the impact of behavioral space, was rebuilt at the urging of Winston Churchill nearly exactly as it had been, since to have changed it, he argued, would change the operation of parliamentary governance. Photo: © Richard Bryant/ Arcaid/Corbis.

1.6. Piazza di San Marco, Venice, Italy, 830–1640. Plan of piazza. Drawing: L. M. Roth.

1.7. Piazza di San Marco. This exterior enclosure contains aspects of physical, perceptual, and b...