![]() Part I

Part I

Framework and Theory![]()

1

The Challenge of Disasters and Our Approach

In at the deep end

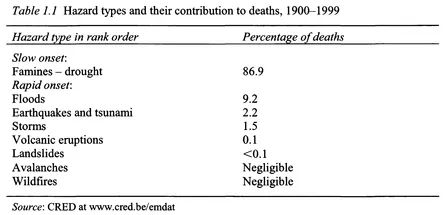

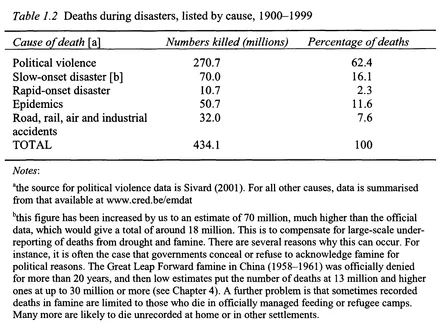

Disasters, especially those that seem principally to be caused by natural hazards, are not the greatest threat to humanity. Despite the lethal reputation of earthquakes, epidemics and famine, a much greater proportion of the world's population find their lives shortened by events that often go unnoticed: violent conflict, illnesses, and hunger - events that pass for normal existence in many parts of the world, especially (but not only) in less developed countries (LDCs).1 Occasionally earthquakes have killed hundreds of thousands, and very occasionally floods, famines or epidemics have taken millions of lives at a time. But to focus on these (in the understandably humanitarian way that outsiders do in response to such tragedies) is to ignore the millions who are not killed in such events, but who nevertheless face grave risks. Many more lives are lost in violent conflict and to the preventable outcome of disease and hunger (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2).2 Such is the daily and unexceptional tragedy of those whose deaths are through 'natural' causes, but who, under different economic and political circumstances, should have lived longer and enjoyed a better quality of life.3

However, we feel this book is justified, despite this rather artificial separation between people at risk from natural hazards and the many dangers inherent in 'normal' life. Analysing disasters themselves also allows us to show why they should not be segregated from everyday living, and to show how the risks involved in disasters must be connected with the vulnerability created for many people through their normal existence. It seeks the connections between the risks people face and the reasons for their vulnerability to hazards. It is therefore trying to show how disasters can be perceived within the broader patterns of society, and indeed how analysing them in this way may provide a much more fruitful way of building policies, that can help to reduce disasters and mitigate hazards, while at the same time improving living standards and opportunities more generally.

The crucial point about understanding why disasters happen is that it is not only natural events that cause them. They are also the product of social, political and economic environments (as distinct from the natural environment), because of the way these structure the lives of different groups of people (see Box l.l).4 There is a danger in treating disasters as something peculiar, as events that deserve their own special focus. It is to risk separating 'natural' disasters from the social frameworks that influence how hazards affect people, thereby putting too much emphasis on the natural hazards themselves, and not nearly enough on the surrounding social environment.5

Many aspects of the social environment are easily recognised: people live in adverse economic situations that oblige them to inhabit regions and places that are affected by natural hazards, be they the flood plains of rivers, the slopes of volcanoes or earthquake zones. However, there are many other less obvious political and economic factors that underlie the impact of hazards. These involve the manner in which assets, income and access to other resources, such as knowledge and information, are distributed between different social groups, and various forms of discrimination that occur in the allocation of welfare and social protection (including relief and resources for recovery). It is these elements that link our analysis of disasters that are supposedly caused mainly by natural hazards to broader patterns in society. These two aspects - the natural and the social - cannot be separated from each other: to do so invites a failure to understand the additional burden of natural hazards, and it is unhelpful in both understanding disasters and doing something to prevent or mitigate them.

Disasters are a complex mix of natural hazards and human action. For example, in many regions wars are inextricably linked with famine and disease, including the spread of HIV-AIDS. Wars (and post-war disruption) have sometimes coincided with drought, and this has made it more difficult for people to cope (e.g. in Afghanistan, Sudan, Ethiopia and El Salvador). For many people, a disaster is not a single, discrete event. All over the world, but especially in LDCs, vulnerable people often suffer repeated, multiple, mutually reinforcing, and sometimes simultaneous shocks to their families, their settlements and their livelihoods. These repeated shocks erode whatever attempts have been made to accumulate resources and savings. Disasters are a brake on economic and human development at the household level (when livestock, crops, homes and tools are repeatedly destroyed) and at the national level when roads, bridges, hospitals, schools and other facilities are damaged. The pattern of such frequent stresses, brought on by a wide variety of 'natural' trigger mechanisms, has often been complicated by human action - both by efforts to palliate the effects of disaster and by the social causation of vulnerability.

During the 1980s and 1990s, war in Africa, the post-war displacement of people and the destruction of infrastructure made the rebuilding of lives already shattered by drought virtually impossible. In the early years of the twenty-first century conflict in central and west Africa (Zaire/Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone) has displaced millions of people who are at risk from hunger, malaria, cholera and meningitis.6 The deep indebtedness of many LDCs has made the cost of reconstruction and the transition from rehabilitation to development unattainable. Rapid urbanisation is putting increased numbers of people at risk, as shown by the terrible toll from the earthquake in Gujarat, India (2001) and mudslides in Caracas, Venezuela (1999).

Box 1.1: Naturalness versus the `social causation' of disasters

When disasters happen, popular and media interpretations tend to focus on their naturalness, as in the phrase 'natural disaster'. The natural hazards that trigger a disaster tend to appear overwhelming. Headlines and popular book titles often say things like 'Nature on the Rampage' (de Blij 1994), and visually the physical processes dominate our attention and show human achievements destroyed, apparently by natural forces. There have been numerous television documentaries in Europe, North America and Japan which supposedly examine the causes of disasters, all of which stress the impact of nature. Much of the 'hard' science analysis of disasters is couched in terms that imply that natural processes are the primary target of research. The 1990s was the UN International Decade of Natural Disaster Reduction (our italics).

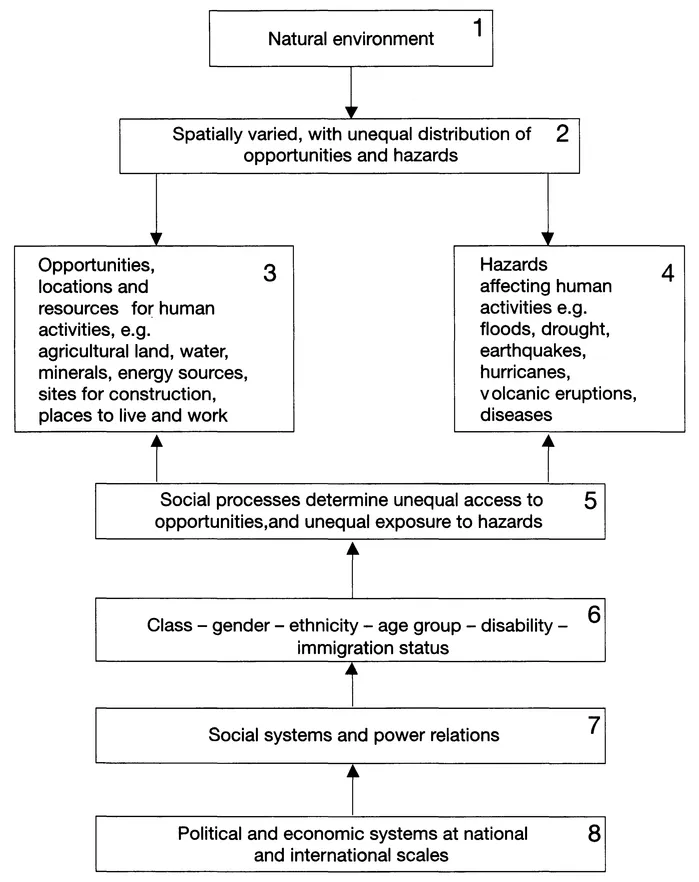

The diagram shown in Figure 1.1 illustrates why this is a very partial and inadequate way of understanding the disasters that are associated with (triggered by) natural hazards. At the top of Figure 1.1, Boxes 1 and 2, the natural environment presents humankind with a range of opportunities (resources for production, places to live and work and carry out livelihoods [Box 3]) as well as a range of potential hazards (Box 4). Human livelihoods are often earned in locations that combine opportunities with hazards. For example, flood plains provide 'cheap' flat land for businesses and housing; the slopes of volcanoes are generally very fertile for agriculture; poor people can only afford to live in slum settlements in unsafe ravines and on lowlying land within and around the cities where they have to work. In other words, the spatial variety of nature provides different types of environmental opportunity and hazard (Box 2) - some places are more at risk of earthquakes, floods, etc. than others.

But crucially, humans are not equally able to access the resources and opportunities; nor are they equally exposed to the hazards. Whether or not people have enough land to farm, or adequate access to water, or a decent home, are determined by social factors (including economic and political processes). And these same social processes also have a very significant role in determining who is most at risk from hazards: where people live and work, and in what kind of buildings, their level of hazard protection, preparedness, information, wealth and health have nothing to do with nature as such, but are attributes of society (Box 5). So people's exposure to risk differs according to their class (which affects their income, how they live and where), whether they are male or female, what their ethnicity is, what age group they belong to, whether they are disabled or not, their immigration status, and so forth (Box 6).

Thus it can be seen that disaster risk is a combination of the factors that determine the potential for people to be exposed to particular types of natural hazard. But it also depends fundamentally on how social systems and their associated power relations impact on different social groups (through their class, gender, ethnicity, etc.) (Box 7). In other words, to understand disasters we must not only know about the types of hazards that might affect people, but also the different levels of vulnerability of different groups of people. This vulnerability is determined by social systems and power, not by natural forces. It needs to be understood in the context of political and economic systems that operate on national and even international scales (Box 8): it is these which decide how groups of people vary in relation to health, income, building safety, location of work and home, and so on.

In disasters, a geophysical or biological event is implicated in some way as a trigger event or a link in a chain of causes. Yet, even where such natural hazards appear to be directly linked to loss of life and damage to property, there are social factors involved that cause peoples' vulnerability and can be traced back sometimes to quite 'remote' root and general causes. This vulnerability is generated by social, economic and political processes that influence how hazards affect people in varying ways and with differing intensities.

This book is focused mainly on redressing the balance in assessing the 'causes' of such disasters away from the dominant view that natural processes are the most significant. But we are also concerned about what happens even when it is admitted that social and economic factors are the most crucial. There is often a reluctance to deal with such factors because it is politically expedient (i.e. less difficult for those in power) to address the technical factors that deal with natural hazards. Changing social and economic factors usually means altering the way that power operates in a society. Radical policies are often required, many facing powerful political opposition. For example, such policies might include land reform, enforcement of building codes and landuse restrictions, greater investment in public health, provision of a clean water supply and improved transportation to isolated and poor regions of a country.

The relative contribution of geophysical and biological processes on the one hand, and social, economic and political processes on the other, varies from disaster to disaster. Furthermore, human activities can modify physical and biological events, sometimes many miles away (e.g. deforestation contributing to flooding downstream) or many years later (e.g. the introduction of a new seed or animal, or the substitution of one form of architecture for another, less safe, one). The time dimension is extremely important in another way. Social, economic and political processes are themselves often modified by a disaster in ways that make some people more vulnerable to an

Figure 1.1 The social causation of disasters

extreme event in the future. Placing the genesis of disaster in a longer time frame therefore brings up issues of intergenerational equity, an ethical question raised in the debates around the meaning of 'sustainable' development (Adams 2001). The 'natural' and the 'human' are, therefore, so inextricably bound together in almost all disaster situations, especially when viewed in an enlarged time and space framework, that disasters cannot be understood to be 'natural' in any straightforward way.

This is not to deny that natural events can occur in which the natural component dominates and there is little place for differential social vulnerability to the disaster other than the fact that humans are in the wrong place at the wrong time. But such simple 'accidents' are rare. In 1986 a cloud of carbon dioxide gas bubbled up from Lake Nyos in Cameroon, spread out into the surrounding villages and killed 1,700 people in their sleep. In the balance of human and natural influences, this event was clearly at the 'natural' end of the spectrum of causation. The area was a long-settled, rich agricultural area. There were no apparent social differences in its impacts, and both rich and poor suffered equally.7

One example of a natural event with an explicitly inequitable social impact is the major earthquake of 1976 in Guatemala. The physical shaking of the ground was a natural event, as was the Cameroon gas cloud. However, slum dwellers in Guatemala City and many Mayan Indians living in impoverished towns and hamlets suffered the highest mortality. The homes of the middle class were better protected and more safely sited, and recovery was easier for them. The Guatemalan poor were caught up in a vicious circle in which lack of access to means of social and self-protection made them more vulnerable to the next disaster. The social component was so apparent that a journalist called the event a 'class-quake'.

It is no surprise that poor people in Guatemala live in flimsier houses on steeper slopes than the rich and that they are therefore more vulnerable to earthquakes. But what kind of social 'fact' is differential vulnerability in a case such as this? Above all, we think this case involves historical facts. Referring to a long history of political violence and injustice in the country, Plant (1978) believed Guatemala to be a 'permanent disaster'. The years of social, economic and political relations among the different groups in Guatemala and elsewhere have led some to argue that such histories 'prefigure' disaster (Hewitt 1983a). In Guatemala, after the 1976 earthquake, the situation deteriorated, with years of civil war and genocide against the rural Mayan majority that only ended in 1996. During this period, hundreds of thousands of Mayans were herded into new settlements by government soldiers, while others took refuge in remote, forested mountains and still others fled to refugee camps in Mexico. These population movements often saw marginal people forced into marginal, dangerous places.

This book attempts to deal with such histories and to uncover the deeply rooted character of vulnerability rather than taking the physical hazards as the starting point, thereby allowing us to plan for, mitigate and perhaps prevent disaster by tackling all its causes. The book also builds a method for analysing the actual processes which occur when a natural trigger affects vulnerable people adversely.

Conventional views of disaster

Most work on disasters emphasises the 'trigger' role of geo-tectonics, climate or biological factors arising in nature (recent examples include Bryant 1991; Alexander 1993; Tobin and Montz 1997; K. Smith 2001). Others focus on the human response, psychosocial and physical trauma, economic, legal and political consequences (Dynes et al. 1987; Lindell and Perry 1992; Oliver-Smith 1996; Piatt et al. 1999). Both these sets of literature assume that disasters are departures from 'normal' social functioning, and that recovery means a return to normal.

This book differs considerably from such treatments of disaster, and arises from an alternative approach that ...