![]()

PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN CONFLICT

Ed Schenkenberg van Mierop

Civilians have always been under threat in war. But the methods of modern warfare seem sometimes to threaten more of them more of the time. In recent years wars have seemed characterised by endless streams of wretched refugees, fleeing violence or mayhem or starvation, being corralled into camps. The western agencies attempt to dispense both aid and protection, often in competition with one another and with the political or military authorities which attempt to dominate the refugees.

Many of these agencies do their best under horrific conditions – and sometimes their best is good. But all too often the help they can offer is at best a short-term palliative. Their works, and the charitable inclinations of their supporters, are exploited for political ends. They are often forced to be part of the problem, not part of the solution. Kurdistan, Somalia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Afghanistan, Liberia – the list goes on and on, with the images of those suffering blurring in and out of focus as attention flickers from place to place, disaster to disaster. At the end of the day the impression that lingers, rightly or wrongly, is that all over the world people are inadequately protected from violence. It is not new that civilian casualties are the purpose rather than the by-product of war. But the numbers of victims are increasing exponentially, and responses seem more and more inadequate.

I suppose one can argue that in the last fifty years there have been three different periods, three different kinds of warfare. First, during and just after the Second World War, conflict was classical – states fighting each other. Second, during the Cold War, the superpowers dominated all. In the period of decolonisation, governments fought guerrilla liberation movements, which were often based on desire for independence and on some form of political morality. Humanitarian organisations had to find some way of working with these movements. The Cold War established certain patterns. In most conflicts there was polarisation induced by the bipolar world. So there was a framework in which the parties were identified.

Since the end of the Cold War, established patterns are now gone. Now there is often a surplus of parties or interlocutors. But none has real authority. This new, third period started after the fall of the Wall in 1989; it is a period of non-structured or destructured conflict – as in Somalia, Liberia, Rwanda, Bosnia – which is sometimes called identity-based. In Somalia, a senior official of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) once said that almost every individual was looking for his own identity and that was the main motivation for the conflict.

Certainly, one can agree with Eric Morris of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), who argues in a new publication that what is happening now is that for the third time this century the world is in the throes of the creation of new states emerging from the collapse of an old world order. And with this process of creation the demands of and for ethnicity have become ever more virulent. No one quite knows what it means – ancient hatred, as Morris points out, has become the catchall cliche to describe and explain it – but its effects have been powerfully destructive, from Rwanda to Bosnia and within the former Soviet Union. Ethnic demands have played an important part in creating something approaching chaos in international relations – at the least disorder.

Since the fall of the Wall, that amorphous entity known as the international community – which usually means a few developed and articulate nations led by or at least influenced by the United States – has made a distinction amongst conflicts. It has been between those which are seen as a real threat to the world’s vital interests – e.g. the invasion of Kuwait – and those that are not – e.g. Rwanda, Somalia and Bosnia. In the first case, peace will be enforced effectively, indeed ruthlessly; in the second, negotiations, monitoring and humanitarianism are deemed adequate. One writer has described this approach – the predominant approach – as ‘containment with charity’.

The idea of ‘humanitarianism’ itself has been inflated. The most obvious and most telling recent example of this has been Bosnia. The West never defined a political objective for the former Yugoslavia. Humanitarianism was used as a cloak for this failure. The badly named UN Protection Force, UNPROFOR, was established not to protect the citizens of former Yugoslavia but the humanitarian relief programmes run (efficiently) by the UNHCR. UNPROFOR undoubtedly saved lives and alleviated much misery. But its other effect was – as with so many relief operations – to reinforce the war parties and extend the war.

Almost all humanitarian agencies try to claim that they are neutral and impartial. This can often be a curse. What matters is the perception of them by different actors in a conflict. In Bosnia the UN and its agencies, supposedly neutral, were decried as biased by all sides. The ICRC rigidly refused to accept the protection of UN armed escorts in former Yugoslavia and ICRC officials argued that they were therefore more widely accepted as truly neutral.

The sorrow of Domanovici

In 1993, I worked as a medical officer with MSF-Holland on a drug distribution programme in war-torn Hercegovina. Besides supporting the existing medical infrastructure there, we assessed the needs of vulnerable groups like displaced persons and psychiatric patients. During this assessment we came across a mental hospital called Domanovici.

The building had been partly destroyed by the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) at the beginning of the war. Though it had been recently repaired by Swiss Disaster Relief, a reconstruction NGO, we found the hospital completely deserted. Its 212 patients were evacuated in 1992 because of nearby shelling and fighting and were sent to four different buildings on the West Bank in Mostar, which was a safe place at that time.

During the spring of 1993 a very bloody war broke out between the Bosnian Government Forces (BiH) and the Bosnian Croats (HVO). We visited one of the buildings where the psychiatric patients lived and saw that the living conditions were appalling. The patients wore only rags and suffered from scabies. lice and fleas. The food was of poor quality and medical care was virtually non-existent. Their fourth-floor accommodation was accessible only by a staircase left completely exposed by shelling.

But what worried us most was the security situation. The building was only 100 metres away from a very active frontline, and the patients were easy targets. Because of their mental disorders they were completely oblivious to security, and all of them were heavily sedated with strong neuroleptics, which caused them to move around very slowly.

When we explained to the UNHCR Protection Officers in Medugorje that it was a serious violation of these patients’ human rights to house them so close to the frontline, the officers agreed to help evacuate them back to the Domanovici mental hospital. But the HVO didn’t allow them to go to Mostar’s West Bank. When we then discussed the situation with the Minister of Health of the self-proclaimed Croatian Republic of Herceg-Bosna, he immediately said that he was not in a position to change anything.

In the meantime, seven patients were murdered and nine wounded by snipers. Five patients who could no longer stand the suffering committed suicide by jumping out of windows. One patient was killed by a grenade while begging on the street for cigarettes. Two others were killed by their own police while unknowingly violating the curfew.

Many innocent people died for nothing. UNHCR knew what was happening, but was powerless to do anything and – even worse – accepted its powerless role. Local high-ranking politicians knew exactly what was going on. But they had other interests and closed their eyes.

The Croatian authorities, we learned, had a hidden agenda. They did not want the psychiatric patients back in Domanovici because they had already designated the building to accommodate Croatian displaced persons. Even worse, HVO wanted to use the building for military purposes.

Our only recourse was to inform the public by releasing the story to the media, including the BBC. Following the Dayton accords, some of the patients were evacuated to Croatia, others to Italy. They never went back to Domanovici.

Fokko de Vries, Dutch Medical Officer, MSF, Mostar

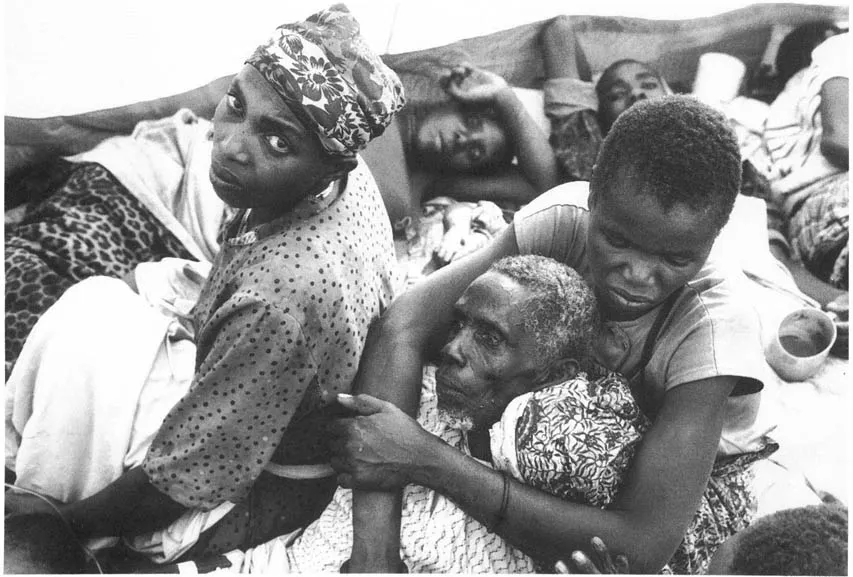

Plate 1.1 Refugees at a cholera treatment centre in Goma, Zaire.

Photograph: Teun Voeten

Indeed, so-called ‘neutral’ and ‘impartial’ intervention can and often does have exactly the opposite effect from that intended – it exacerbates the suffering by prolonging the conflict. All this behind what has been called the humanitarian alibi or even ‘fig-leaf’. But those attempting to use the alibi and to hide behind the fig-leaf have found that in recent years many humanitarian operations have become more difficult. Interlocutors cannot be relied on. And funding for protection is harder and harder to find. Indeed, it would be impossible alone. Protection has to be carried and financed on the back of relief operations.

Another change is that previously the parties – guerrillas and governments – received a lot of assistance from outside. Now they need to raise money. But here a conflict arises. Relief requires the cooperation of the authorities – as Bosnia demonstrates. Protection often demands confrontation. In Bosnia and elsewhere the traditional duty of protection of individuals has often been sacrificed to the logistical requirements of the feeding systems. More time has been spent on protecting wheat and rice than people.

In Africa there have been, in the last two years, at least 25 countries in which civilians have been subjected to greater or lesser degrees of violence. Amongst those places where there have been the most serious abuses are the Great Lakes region (East Zaire, Burundi, Rwanda); Angola; Liberia; Sierra Leone and neighbouring countries; southern Sudan; Somalia – because no real solution has been found there.

Plate 1.2 Burmese Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aug San Sun Kyi speaks to a crowd in Rangoon, Burma.

Photograph: Jan Banning

In Liberia the ICRC was forced to evacuate its foreign staff in April 1996 – for the fourth time in the country’s six-year war – because conditions had once again become so dangerous. Jean-Daniel Tauxe, a senior ICRC official, wrote chillingly, ‘Teenage fighters high on drink or drugs steal our vehicles. They then drive off to bring in reinforcements who follow suit, multiplying the looting and anarchy at the expense of the ordinary Liberians we seek to help. What do we do?’ he asked. His answer was that humanitarian organisations could do nothing – the solution had to be found in the Security Council.

In Somalia, the humanitarian operation (UNOSOM) failed because no one understood what the troops were there for. UNOSOM failed also because soldiers are now no longer allowed to do their jobs. A principal reason why UN operations falter today is the zero casualties option. One of the biggest misunderstandings at the end of this century is that people expect military–humanitarian missions to bring peace and stability. As presently arranged, they cannot. Indeed, it is arguable that if soldiers are not prepared (or allowed) to do their traditional job they are rarely worth deploying.

Plate 1.3 Armed mujahideen, or holy warriors, formerly involved in Afghanistan’s decade-long war against the Soviets, are now caught up in a civil war of their own with devastating costs for the country’s civilian population.

Photograph: Bart Eijgenhuijsen

The lessons of Somalia, learned in particular in Washington, were applied to most awful effect in Rwanda – so far. It was here in 1994 that genocide, the most extreme abuse of human rights yet devised – took place. It was seen to happen and yet elicited no effective riposte from the world outside. The explanation for this was given quite clearly at the time by Kofi Annan, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping. He explained that it was the post-Somalia syndrome. On 17 May 1994, Security Council Resolution 918 actually authorised the extension of the mandate of the UN peace-keeping force (UNAMIR) in Rwanda. But, following the loss of 18 US Army Rangers in Somalia, the USA was unwilling to have the UN launch an enforcement action to stop the genocide. And without US backing, as Morris has pointed out, the UN simply did not have the institutional capacity to respond. In order to avoid any form of responsibility for intervention, the word ‘genocide’ was never used during that period in any of the official texts or resolutions. The international community preferred to use the phrase ‘humanitarian crisis’ which implicitly places the logistics of aid well before the issue of protection.

In place of UN intervention, late and by no means replacing an early international response, the French government sent its own force, called Operation Turquoise. This venture was much criticised. And for good reason. It allowed numerous criminals to find a previously unimagined form of exile in the French-established security zone. Yet it did save lives within the safety zone that it created. It diminished the flow of refugees to Zaire, it protected some of those Tutsis who remained alive and some Hutus against revenge killings.

But the main thrust of the international response to the catastrophe in Rwanda was in refugee relief in Goma. There, once again, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and international organisations set up a vast, sometimes even macabre, humanitarian bazaar. By spring 1996 the relief operation for the Rwandan refugees had cost at least one billion dollars – and to what end? Keeping people alive in a state of limbo and uncertainty which held no real hope for their future under the authority of those who represented the former regime responsible for the genocide.

Long gone, it seems now, are the heady days after the fall of the Wall when politicians spoke of a new world order. As Boutros Boutros Ghali put it, in his downsized Supplement to an Agenda for Peace, ‘Collectively Member States encourage the Secretary-General to play an active role in this field; individually they are often reluctant that he should do so when they are party to the conflict’.

The Secretary-General also pointed out that It would be folly to attempt [an enforcement capacity] at a time when the Organisation is resource starved and hard pressed to handle the less demanding peace-making and peace-keeping responsibilities entrusted to it.’ Indeed.

By early 1996, it was becoming increasingly clear that a catastrophe similar to that of Rwanda was about to befall Burundi. There was what some called a ‘slow genocide’ with dozens, sometimes scores or even hundreds, of people murdered every week. By April the numbers of deaths were estimated to have risen to 100 a day and, in all, at least 50,000 Burundians are thought to have been killed in the last two years.

Almost all these victims were civilians. The killings were often conducted in the most brutal fashion. Abou...