eBook - ePub

Factor Analysis

Richard L. Gorsuch

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 448 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Factor Analysis

Richard L. Gorsuch

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Comprehensive and comprehensible, this classic covers the basic and advanced topics essential for using factor analysis as a scientific tool in psychology, education, sociology, and related areas. Emphasizing the usefulness of the techniques, it presents sufficient mathematical background for understanding and sufficient discussion of applications for effective use. This includes not only theory but also the empirical evaluations of the importance of mathematical distinctions for applied scientific analysis.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Factor Analysis als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Factor Analysis von Richard L. Gorsuch im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Psicología & Historia y teoría en psicología. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1 Introduction

A basic review of the role of factor analysis in scientific endeavors is necessary background for the presentation of factor-analytic procedures. The overview is begun in Section 1.1, Science and Factor Analysis, where factor analysis is placed within a general perspective of science. In Section 1.2 it is noted that factor analysis—like any statistical procedure—is simply a logical extension of methods people have always used to understand their world. Some common-sense procedures often used to achieve the goals of factor analysis are noted. This section is concluded by pointing to the limitations of these elementary procedures and by indicating that some of the limitations are overcome through the more powerful factor-analytic techniques. The chapter concludes with background on examples that are used throughout the book (Section 1.3).

1.1 SCIENCE AND FACTOR ANALYSIS

A major objective of scientific activities is to summarize, by theoretical formula-tions, the empirical relationships among a given set of events. The events that can be investigated are almost infinite, so any general statement about scientific activities is difficult to make. However, it could be stated that scientists analyze the relationships among a set of variables where these relationships are evaluated across a set of individuals under specified conditions. The variables are the characteristics being measured and could be anything that can be objectively identified or scored. For example, a psychologist may use tests as variables, whereas a political scientist or sociologist may use the percentage of ballots cast for different candidates as variables. The individuals are the subjects, cases, voting precincts or other individual units that provide the data by which the relationships among the variables are evaluated. The conditions specify that which pertains to all the data collected and sets this study apart from other similar studies. Conditions can include locations in time and space, variations in the methods of scoring variables, treatments after which the variables are measured, or, even, the degrees of latitude at which the observation is made. An observation is a particular variable score of a specified individual under the designated conditions. For example, the score of Jimmy on a mathematical ability test taken during his fifth-grade year in Paul Revere School may be one observation, whereas Mike's score on the same test at the same school might be another. (Note that observation will not be used to refer to an individual; such usage is often confusing.)

Although all science falls within the major objective of building theories to explain the interrelationships of variables, the differences in substantive problems lead to variations in how the investigation proceeds. One variation is the extent to which events are controlled. In traditional experimental psychology and physics the investigator has randomly assigned subjects to the various manipulated conditions, whereas astronomers have, until recently, been concerned with passive observations of naturally occurring events. Within any broad area, some scientific attempts are purely descriptive of phenomena, whereas others seek to generate and test hypotheses. Research also varies in the extent to which it utilizes only a few variables or utilizes many variables; this appears to be partly a function of the complexity of the area and the number of variables to which a discipline has access.

Regardless of how the investigator determines the relationships among variables under specified conditions, all scientists are united in the common goal: they seek to summarize data so that the empirical relationships can be grasped by the human mind. In doing so, constructs are built that are conceptually clearer than the a priori ideas, and then these constructs are integrated through the development of theories. These theories generally exclude minor variations in the data so that the major variations can be summarized and dealt with by finite beings.

The purpose in using factor analysis is scientific in the sense previously discussed. Usually the aim is to summarize the interrelationships among the variables in a concise but accurate manner as an aid in conceptualization. This is often achieved by including the maximum amount of information from the original variables in as few derived variables, or factors, as possible to keep the solution understandable.

In parsimoniously describing data, factor analysts explicitly recognize that any relationship is limited to a particular area of applicability. Areas qualitatively different, that is, areas where relatively little generalization can be made from one area to another, are referred to as separate factors. Each factor represents an area of generalization that is qualitatively distinct from that represented by any other factor. Within an area where data can be summarized (i.e., within an area where generalization can occur) factor analysts first represent that area by a factor and then seek to make the degree of generalization between each variable and the factor explicit. A measure of the degree of generalizability found between each variable and each factor is calculated and referred to as a factor loading. Factor loadings reflect quantitative relationships. The farther the factor loading is from zero, the more one can generalize from that factor to the variable. Comparing loadings of the same variable on several factors provides information concerning how easy it is to generalize to that variable from each factor.

Example

Numerous variables could be used for comparing countries. Size could be used by, for example, counting the number of people or the number of square kilometers within the borders of that country. Technological development could be measured by the size of the transportation systems or the size of the communications systems. Indeed, the number of variables is almost infinite by which countries could be compared. To what extent can this large number of variables be considered as manifestations of more basic constructs or factors? To the degree that the variables are interrelated and represent a few factors, then, it will be possible to develop a theory for each factor but still explain a large number of variables.

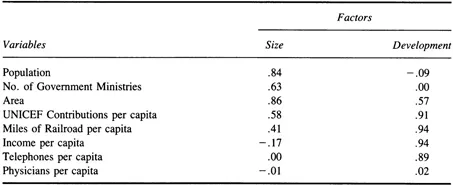

Table 1.1.1 presents the results of a typical factor analysis. Cattell and Gorsuch (1965) correlated demographic variables across countries, and factored them by the iterated principal axis procedure described in Chapter 6. The factors were then rotated to visual simple structure, a procedure described in Chapter 9. The factor loadings relating each variable to each factor are given in Table 1.1.1.

TABLE 1.1.1 Factor Pattern Loadings of Demographic Variables on Two Factors

Note: The Table is based on data collected in the 1950s from 52 individual countries. The elements in the table are the weights given to the factor standard scores to reproduce or estimate the variable standard scores. (Adapted from Cattell & Gorsuch, 1965.)

From the set of variables having large loadings, it can be easily seen that the factor labeled development is distinct from the factor representing the size of the country. If it is known that the country has a high score on an operational representative of the development factor, then it can be concluded that the national income per capita, telephones, and the other variables with high loadings on this factor will also be prominent. A different set of generalizations can be made if the size of the country is known, because that is an empirically different content area.

Some variables overlap both of the distinct factors, for example, the miles of railroad per capita. Others may be unrelated to either factor, as is the physician rate; no generalizations can be made to it from the factors identified in this analysis.

Some Uses of Factor Analysis. A statistical procedure that gives both qualitative and quantitative distinctions can be quite useful. Some of the purposes for which factor analysis can be used are as follows:

- Through factor-analytic techniques, the number of variables for further research can be minimized while also maximizing the amount of information in the analysis. The original set of variables is reduced to a much smaller set that accounts for most of the reliable variance of the initial variable pool. The smaller set of variables can be used as operational representatives of the constructs underlying the complete set of variables.

- Factor analysis can be used to search data for possible qualitative and quantitative distinctions, and is particularly useful when the sheer amount of available data exceeds comprehensibility. Out of this exploratory work can arise new constructs and hypotheses for future theory and research. The contribution of exploratory research to science is, of course, completely dependent upon adequately pursuing the results in future research studies so as to confirm or reject the hypotheses developed.

- If a domain of data can be hypothesized to have certain qualitative and quantitative distinctions, then this hypothesis can be tested by factor analysis. If the hypotheses are tenable, the various factors will represent the theoretically derived qualitative distinctions. If one variable is hypothesized to be more related to one factor than another, this quantitative distinction can also be checked.

The purposes outlined above obviously overlap with purposes served by other statistical procedures. In many cases the other statistical procedures can be used to answer the question more efficiently than one could answer them with a factor analysis. For example, if the hypothesis concerns whether or not one measure of extroversion is more related to a particular job performance than another, the investigator can correlate the two variables under consideration with an operational representative of the job performance. A simple significance test of the difference between the correlation coefficients would be sufficient. This is actually a small factor analysis in that the same statistics would result by defining the operational representative of job performance as the first diagonal factor (see Chapter 5) and determining the loadings of the two extroversion variables on that factor. Although the result would be exactly the same, proceeding factor analytically would be to utilize an unnecessarily complex approach.

Many traditional statistics can be viewed as special cases of the factor-analytic model where, because of their limited nature, detailed statistical theories have been developed that greatly enhance the statistic...