eBook - ePub

Introduction To The Economics Of Water Resources

An International Perspective

Stephen Merrett

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 228 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Introduction To The Economics Of Water Resources

An International Perspective

Stephen Merrett

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

A concise treatment of water-resource economics. Based upon political economy perspectives, it draws upon a range of case-studies - Third- World, developed world, and former communist countries - to cover many issues. There is guidance on

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Introduction To The Economics Of Water Resources als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Introduction To The Economics Of Water Resources von Stephen Merrett im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Sunlight, air, the soil and water—these are the fundamental requirements of all life on Earth. In the specific case of water, the human body cannot survive without it, it plays a vital part in sanitation for our rural and urban communities, it is necessary to all forms of agriculture, and is demanded for the majority of industrial processes. So, water is a key natural resource for human society.

Unlike sunlight and air, we know that rivers, lakes, estuaries and coastal waters can all be appropriated into the ownership of public or private bodies. For this reason alone, water is not merely a natural resource but also an economic resource. This is true even though in many countries no price is set on water’s use, no sum of money charged per unit consumed. This is the case whenever users enjoy unrestricted physical access to fresh water; and also where water is supplied to users by public or private water companies but its volume is not measured. In the latter case, water charges are widely collected by means of a fixed charge levied on water consumers.

Priced or not, we should still recognize that for most societies the collection and distribution of fresh water requires human labour and, often, civil engineering infrastructures, as was the case in ancient Egypt, Imperial China and the Inca civilization. So, for this reason too, water is and always has been an economic resource. In more recent times, this understanding has become much more widely accepted because of the economic and financial costs imposed by laws to protect water quality; because of water scarcity and the associated competition between users; and as a result of the global shift to the privatization of public sector infrastructures since the end of the 1970s.

If water is so fundamental a biological and social requirement, and if it is now widely recognized to be an economic good, then there is a need for hydroeconomics—the economics of water resources—and there is a potentially varied audience with an interest in that subject. This book is intended to meet the needs of both students and professionals in the fields of economics, engineering, environmental science, environmental studies, geography and hydrology. As an introduction to the subject, prior knowledge is assumed of neither economics nor hydrology. To facilitate the learning process, the analytical content of each of the next seven chapters is always followed by one or more case studies, drawing their material from countries as diverse as the UK, Slovakia, Latvia, the USA, Peru, Jordan, Malaysia and Australia.

If, then, a political economy of water resources exists, what may be said to be its subject areas, that is, what human activities does it address? Since no grand academy determines the content of the subdisciplines of economics, the answer to this question embodies an element of personal judgement. I shall define the subject areas of hydroeconomics as:

• nature conservation for rivers, lakes, wetlands, estuaries and coastal waters

• land drainage

• flood control and coastal defence

• dam projects

• the supply of fresh water

• the use of water by households, agriculture, industry and other sectors

• the treatment of wastewater and its disposal.

Note that this definition does not include fishing, navigation or water-based recreation. Although the hydroeconomist will require some empathy with these areas, they can best be regarded as components of the economics of fishing, transport and leisure respectively. At the same time, hydroeconomists can expect their passion for nature conservation to be shared with environmental economists, the analysis of dams to be strengthened by familiarity with the economics of energy, and the study of the demand for water by farmers to draw fruitfully on the economics of agriculture. Human culture is never neatly separable into discrete dimensions, nor is political economy. To restate the position, the primary orientation of the economics of water resources is to water that is abstracted, stored and distributed by human labour, to the use of that water, and to the disposal of wastewater.

With the subject areas of hydroeconomics specified, it is possible to formulate its substantive concerns. Once again, an element of personal judgement is necessary. The substantive concerns of hydroeconomics, which can be expressed as the guiding criteria it requires for the development of analysis and policy, are as follows:

• to supply water of sufficient quantity and appropriate quality to users in households, agriculture, industry and other sectors

• to ensure the use of fresh water is affordable to low-income households

• to ensure the husbandry of water in its supply and use

• to purify water from domestic, agricultural and industrial effluents

• to prevent the abuse of monopoly power in the supply of fresh water and the collection of wastewater

• to protect rural and urban communities against floods and to drain the land of stormwater

• to protect water’s hydrocyclical capacity to renew its ground- and surface- water flows

• to conserve natural species and habitats in all their fresh- and coastal-water environments

• to reduce and eliminate water-driven international conflict

• to ensure that, when government expenditure takes place for these purposes, it is spent wisely.

The economic paradigm that provides the analytical foundation of this book deserves mention. This is evolutionary political economy, rather than Marxist economics or neoclassical economics—the two dominant economic paradigms of this century.1 An important expositional text is Hodgson et al. (1994). It is used hereafter as a reference point throughout my own book, which attempts, for the first time, to apply evolutionary political economy to the supply and use of water resources and which, at various junctures in the text, also develops specific criticisms of neoclassical orthodoxy. Hodgson et al. (1994) is a good starting point for those who may wish to explore evolutionary political economy further.

The book’s analytical structure is as follows. Chapter 2 gives an overview, from a physical infrastructural point of view, of the supply of fresh- and wastewater services. Chapter 3 follows with an account of the costs of supplying these services. Chapter 4 complements the two initial supply-side perspectives with a review of the economics of effective demand and of the price of water. In Chapter 5, an exposition is given of the techniques of social cost-benefit analysis with respect to water projects, and Chapter 6 matches this with an outline of financial accounting for water enterprises. Chapters 7 and 8 are concerned respectively with water’s role in achieving a sustainable society and the valuation of the environmental costs and benefits of water projects. The final chapter gathers together the principal conclusions of the whole work. From this brief listing of chapters it can be seen that the central analytical themes developed in addressing the substantive concerns of hydroeconomics are supply, effective demand, project analysis, enterprise finance and the sustainable management of water resources.

The main body of the text is followed by a glossary, the references and a useful index. From Chapter 2 onwards where a term will be placed in the glossary, it is formatted in bold the first time it occurs in the text. Please note, too, that in the presentation of numbers, English practice is used. For example, 1243 is one thousand, two hundred and forty-three, whereas 1.243 is a decimal expression.

1. In Europe, the professional association committed to the development of the paradigm is the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy (EAEPE).

CHAPTER TWO

Supply: the engineer’sperspective

2.1

The hydrological cycle

The hydrological cycle

Evolutionary political economy focuses on the substance of the fundamental processes involved in providing necessary goods and services for humankind. So, rather than make a beginning with the economic theory of supply, here we start with an overview of the natural world’s hydrological cycle, moving on to the engineering activities of what I shall call the hydrosocial cycle in the supply of fresh-and wastewater services.

Water held in the oceans and other water bodies, as well as in the land masses and their vegetation, continuously evaporates into the global atmosphere, whence it returns to the Earth through precipitation, primarily as rainfall. On land it gathers as surface water and infiltrates as groundwater. Surface water is the flow of streams and rivers in spatially distinct catchment areas, as well as their associated freshwater pools, wetlands, lakes, inland seas and river deltas. Groundwater is found below the land’s surface, and includes that contained in aquifers. Such aquifers help to sustain surface-water flows. Of all the world’s water, 97.4 per cent is in the oceans and 2.6 per cent is land-based, with an additional tiny fraction held in the atmosphere. Of all the land’s water, 76.4 per cent is in ice caps and glaciers, 22.8 per cent occurs as groundwater, and 0.6 per cent is surface water, half of it in saline seas (Ward & Robinson 1990: table 1.1).

Water can be measured in stock terms, that is, the volume present in a particular place at a point in time. Examples are the size of an aquifer, or of a lake, estimated in cubic metres. Water quantities are also calculated in flow terms, the volume reaching or passing a defined point or area in any time period. Examples are a spring’s flow in litres per second, or a river’s flow in cubic metres per day, or rainfall in a region in millimetres depth per year. The term “capacity” in water planning is sometimes used to refer to a stock of water, as with “the capacity of a reservoir”, and sometimes to a flow, as with the annual capacity of a water treatment plant.

2.2

The hydrosocial cycle

The hydrosocial cycle

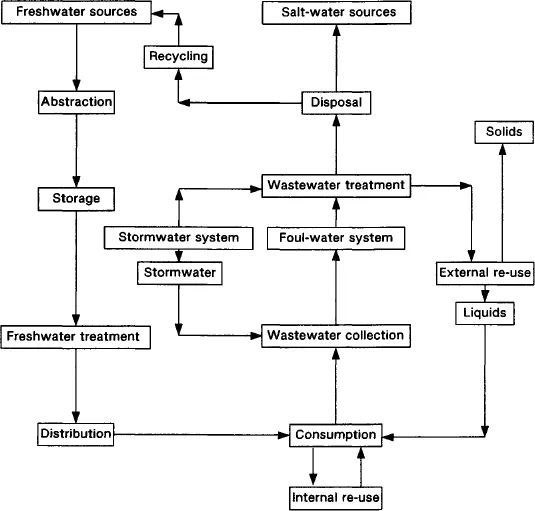

The engineering activities of the hydrosocial cycle in the supply of fresh- and wastewater services are illustrated in Figure 2.1. Seven boxes there are of special importance: abstraction, storage, freshwater treatment, freshwater distribution, wastewater collection, wastewater treatment, and wastewater disposal. Each of these processes will be considered in turn, as well as the demand-side activity of consumption, which lies between freshwater distribution and wastewater collection.

A starting point is the natural flow in a catchment which is available for the conversion from natural resource to social product. This flow varies during the course of the year because of the changing seasons. Moreover, there is year-on- year variation: an abundance of rain in one 12-month period may be succeeded by long, dry spells in the next. Of course, these seasonal and annual supply variations differ markedly between regions and countries.

Figure 2.1 A simple model of the hydrosocial cycle.

The theoretically available resource is referred to as effective rainfall, that is, total rainfall in an area minus that lost both through transpiration by foliage and through surface evaporation. In a supply forecasting context, widely used measures are the effective rainfall during average rainfall years, as well as effective drought rainfall, that available in a drought of a severity which could be expected to recur, for example, once in every 50 years.

Abstraction takes place from groundwater, from freshwater surface sources, from saline inland seas, from tidal sources and from the open sea. In these last three cases (of saline water) our interest is where brackish estuarine water is used for specific purposes such as cooling in electricity generation, or where sea water is treated in desalination plants.

The abstraction of fresh water may be directly by the user, such as in a riverside village, on a farm, in an industrial firm or for a hydroelectric power station; or it may be by a water company, which supplies the water as a service. Water companies can be in public or private ownership. In the European Union (EU), for example, direct users as well as water companies must have an abstraction licence, which defines the maximum flow which it is permissible to take.

Abstraction requires source works. In the case of groundwater, boreholes are driven down into the aquifer, and pumping equipment is installed to get the water to the starting point of the hydrosocial network. Accessing surface water is easier but still requires source infrastructures.

There is more than one definition of abstraction...