![]()

1 Asia’s development model

Asia is moving into a leadership role in the world economy1

We live in Asia’s century. If neither China nor any other Asian state dominates the twenty-first century in the way that Britain and the United States were successive geopolitical leaders in the preceding 200 years, the region as a whole will still influence world affairs as never before in modern times. The twenty states and territories that we take to comprise East and South Asia are home to over 3.6 billion people or 53 per cent of the world’s population. This region is host to many hundreds of indigenous languages and its cultural roots include important Austro-Asiatic, Austronesian, Dravidian, Indic, Japonic, Sino-Tibetan and Tai-Kadai traditions, each of which is distinct. Western influences have impacted the region at recurring intervals but only embedding in the former settlement colonies of Australasia. Breadth of scale in resource endowments, institutional origins and culture means that it is often difficult to generalize about Asia or its economies. Yet two factors of interest to us are widely shared, a supervening concentration on economic development and a strong desire for social stability, two preferences that can sometimes conflict.

Asia has huge disparities of wealth and income, for as China and Japan are ranked second and third among world economies measured by nominal national output, so several are among the most modest. Thirty years of unusually rapid and consistent growth led China to overtake the United States during 2010 to become the world’s leading producer of manufactured goods (IHS Global Insight 2010). China’s economy has doubled in terms of annual output every seven to eight years since the early 1980s with striking results in those regional economies with which it engages in trade (Arora & Vamvakidis 2010) – today almost every economy in the region and world. In 2008, a major study supported by the World Bank and several OECD governments sought to identify conditions conducive to growth since 1945 among 13 selected developing economies (Commission On Growth & Development 2008; Lin & Monga 2010). It hoped to encourage similar policies elsewhere to lessen poverty. Nine of the sample were East Asian: China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand, with only one each drawn from Africa, the Americas, Europe or the Middle East. Five broad factors were said to be common to the group:

• Openness to the global economy;

• Macroeconomic stability;

• High rates of saving and capital investment;

• Market-based resource allocation; and

• Effective political leadership and governance.

A number of contrasting factors were said to be negative for development. We will explore the findings at greater length below. The report and its findings have been highly influential, reflecting a pragmatic approach to development and one deviating strongly from the Washington Consensus, which we discuss in Chapter 2. Only Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are ranked by the IMF as low income East Asian countries if Myanmar (Burma) and North Korea are excluded from analysis (IMF 2010a).

Asia’s post-1949 record shows a pattern of state-influenced development but with an increasing market orientation, typically with less reliance on official aid or concessionary finance than other regions, a trait considered unconventional by the traditional developmental literature. So despite the region’s wealth and income diversity, common features exist among Asia’s economic successes that we shall highlight in this chapter and throughout the book. We also detail systemic limitations in the region’s development model and their implications for future policy. The global financial crisis of 2008 increased interest in Asia’s world standing, not least because China and the neighbouring economies with which it shares trade, investment and manufacturing links became the principal sources of global post-crisis growth after 2009. At the same time, we will argue that Asia may usefully consider institutional reforms to strengthen its domestic and regional financial systems. A lack of realizable and prudent investment channels leads capital to be diverted elsewhere, and an accumulation of foreign currency reserves since 2000 signifies a relative incompleteness in domestic and regional finance and a profound opportunity cost to domestic welfare.

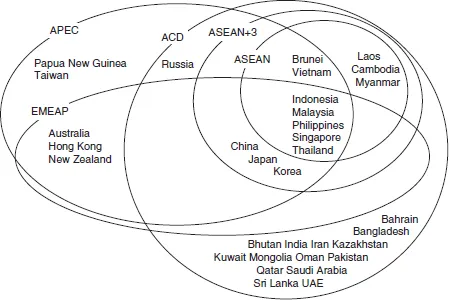

Our purpose in this chapter is to establish a setting in terms of modern economic history and growth theories for the more detailed studies of financial systems and activity that form the core of the book. The analysis covers a territory that varies slightly from topic to topic, although this will always be clear from each section’s context. Equivocation about Asia’s components is common in several academic disciplines, especially when discussing political and economic alliances (see Section 12.4). Some regional groups cover many more states or territories than others as Figure 1.1 shows.

Although the EU has expanded periodically since 1972 ‘Western Europe’ is more fixed as a concept than East Asia. In terms of scope, Finance in Asia covers the territory south from China and Japan to Indonesia and latitudinally between Malaysia and the Philippines. Our analysis excludes the poorest economies and those with insignificant financial sectors, notably Brunei, North Korea, Macau, Myanmar and Timor-Leste. In some instances we use examples of financial practice in India or Australia and from the West, and in common with market custom we occasionally discuss financial activity in non-Japan Asia, that is, East Asia but excluding Japan. This is usually to avoid the immense Japanese financial sector distorting our presentation of other domestic markets that are far smaller in scale. Our focus is with the nine principal members of ASEAN+3 together with Taiwan and Hong Kong, a combined population of 2.09 billion compared to 1.56 billion in South Asia (CIA 2010).

Finally in these opening remarks, three points of language are important. First, the geographical scope of the book is with states and territories in the eastern sections of the Eurasian land mass. We use ‘Asia’ and ‘East Asia’ interchangeably to refer to that area, and not to something larger, either topographically or conceptually. Second, no reference to ‘Asia’ should be taken to infer dependency in any context. Last, some commentators have described certain recently industrialized economies as ‘tigers’ but we use the term sparingly. The economies we examine are not feline or near extinction, even though they may be notably powerful.

Figure 1.1 Regional political and economic groups.

Key: ACD – Asia Cooperation Dialogue; APEC – A...