![]()

– Part I: Pre-1789 –

Foundations of the Movement

Care for Old Buildings in the Pre-Modern Age

![]()

– 1 –

Harbingers of Heritage

Antiquity, Christendom, Renaissance

Some people were talking about the temple and the fine stones and votive offerings with which it was adorned. He said, ‘Those things you are gazing at – the time will come when not one stone of them will be left upon another; all will be thrown down.’

Luke 21, 5–71

THE story of the modern Conservation Movement that dominates this book belongs overwhelmingly to Europe and America, and to the two centuries following the French and Industrial Revolutions. But the Movement’s roots are long, stretching right back to classical Greece and Rome. Indeed, the very fact that the Conservation Movement can be interpreted as a ‘movement’ at all, is a consequence of the momentous changes that began in classical antiquity, in how people saw the relationship of past, present and future – a relationship within which the built environment played a central role.

In pre-classical civilisations, in the Middle East, India or China, there was little concept of historical progression, and the combination of ingrained social hierarchies and polytheistic religion encouraged a tremendous stability, often symbolised through monumental architecture: many sacred sites experienced multiple layering and reappropriation over millennia. In Ancient Egypt, everything was assumed to stay exactly the same, including the monarchy, with its dynasties spanning over two millennia and its pharaonic religion, interrupted only by the brief, monotheistic aberration of the reign of Akhenaten (1364–47 BCE). This unchanging cultural character was expressed in the stone-built monumentality of its architectural set pieces, such as the vast temple complex of Western Thebes, revered from 2000 BC to about AD 500 as the seat of Amun-Re, king of the gods. Reflecting Egyptian belief in the circular character of time, Amun was thought to return annually to be reborn in the Luxor temples (built cumulatively over several hundred years in c.1500–1230 BC). To the north was the massive Karnak Temple where Amun ‘lived’ for the rest of the year. Across the river in the ‘land of the dead’, the Valley of the Kings and of the Queens housed the royal dead of the New Kingdom in a succession of grand mortuary temples, such as that of Amenhotep III (builder of most of Luxor Temple) – a landscape that fused natural and built environments. Although these mortuary precincts often fell into ruin or were looted, their rise and fall followed no conscious framework of ‘progress’: the monumental commemorative statues that dotted them were not monuments in the modern sense, but religious objects, invested with unchanging divine force, like the buildings themselves. In the Mesopotamian civilisations, a similar theocratic traditionalism prevailed and sites such as the multi-layered ziggurats of Babylon were constantly reused. Later and more advanced civilisations elsewhere, such as China in the age of Confucius (551–479 BC), also emphasised stability and deference to ancestral practices and to the family unit.2

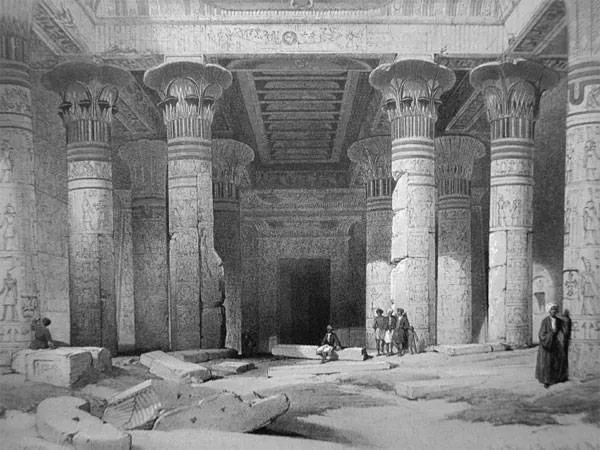

Figure 1.1 David Roberts, grand portico of the Temple of Philae, Nubia (from Views of Egypt and Nubia, c.1847–9)

In all these eras and places, there was often an intense care for old structures, varying in character depending on whether local building tradition stressed masonry (as in the Middle East) or timber (requiring periodical renewal). Nowhere, however, was there conscious conservation in the modern sense, still less historically informed concepts such as ‘authenticity’. Polytheistic religion encouraged a static view of a world in which the sacred was completely intermingled with perceptible reality, and in which everyday objects or places could be invested by gods or ancestral spirits. These had a real call on the respect of the living – and, in turn, their sacred aura could help bolster the ruling order among the living.

This situation only began to alter a little in Mycenean Greece – one of the first societies where change, rather than stability, became a norm. Traces of this process, the first ‘fashions’ in artefacts, are discernible through archaeological investigation, with pot-sherds traceable to a specific century. The restless, seafaring Greeks no longer assumed that the best thing was that which had existed since time immemorial: civilisation began to ‘go faster’. And inevitably, in due course, that new restlessness was consciously articulated, in 5th-century-BC Athens’s outpouring of written and built celebrations of the rise of its civilisation. In classical Athens, we have almost arrived at a concept of historical progress, with a semi-secular nation-state commissioning built monuments to its own advances. In 5th-century Athens, concepts, fashions and leaders followed each other with bewildering rapidity: condemnation hot on the heels of praise. More happened here in a hundred years than in a millennium and a half in Egypt, and the Athenian Oath looked on to the future, pledging that ‘we will transmit the city, not only not less, but greater and more beautiful than when transmitted to us’; the reconstruction of the Acropolis Wall after the Persian War emphasised the visible heritage of surviving masonry.3

But classical Greece, including the diverse Hellenistic world established by Alexander’s descendants, was still a polytheistic society. Its most costly and monumental constructions were almost invariably associated with religion, and thus were mixed together with the need for respect to the gods and ancestors. Within the house, that meant maintaining household shrines – whose aura underlined the authority of the master over family and slaves. The same principle was displayed publicly, on a greater scale, in temples of priestly cults, supplemented by the monuments erected by great men to their achievements and conquests, including statues, triumphal arches, inscriptions, great public buildings and their own tombs. It was the duty of subsequent generations to honour and maintain these, as it was their duty to honour the gods.

In Greek art, the principle of imitation generally prevailed, and there was a strong concern for repair and restoration of old statues and temples. The intermixing of religion and secular life bolstered the ruling order, which invariably claimed the sanction of the gods, through founding myths or the claim of monarchies that their leaders were semi-divine themselves. In Greece, the word for the public built evocation of religious respect was mnema or mnemeton – literally, a spur to memory. In the built environment, this represented an ethical codification of the universal principle of respect and reappropriation of sacred sites. Destruction of temples was universally seen as a violation of morality. But the same could apply to secular monuments too. For example, in the 4th–century BC, when Alexander the Great overthrew the Achaemenid Persian empire, he showed careful respect to the tomb of Cyrus the Great, 6th-century BC founder of the Persian empire. Shocked that it had been plundered by robbers, he had it repaired and had Cyrus’s memorial inscription reproduced in Greek.4Destruction of temples, a much greater sacrilege, could be commemorated through leaving ‘intentional ruins’. Following the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480–79 BC, an inscription at Plataea recorded that ‘I will not rebuild any of the temples that have been burnt and destroyed by the barbarians, but I will let them be left as a memorial to those who come after, of the sacrilege of the barbarians’. And indeed, very few temples were built in Greece in the 30 years after the Persian War.5

Classical antiquity also saw the first restorations, not only of buildings but also of paintings and sculpture – for example, of the Parthenon in 398 BC after the Peloponnesian War. But by the Hellenistic period and later antiquity, sites such as the Athenian Agora, and the Delos and Olympia complexes had become vast open-air museums. In the description of Greece by Pausanias, a traveller of the 2nd century AD, renowned ancient monuments were recorded as still in use, often through like-for-like replacement of decayed elements – as with the wooden columns of the 500-year-old Temple of Hera at Olympia. The Temple of Zeus in that complex, originally built in c.470–50 BC, was repeatedly rebuilt in the following centuries, until finally the statue of Zeus was removed by a private collector to Constantinople in the 5th century AD. Plutarch, writing around AD 75, related the story of the boat of Theseus, allegedly preserved by the Athenians until 310 BC by successive replacement of rotted planks: contemporaries had speculated whether the resulting object was the ‘real’ boat or not. The first secular relics were bound up with religious sites: Vitruvius recorded that ‘in Athens, there is on the Areopagus an example of ancient building roofed with clay to this day’.6

Figure 1.2 The Temple of Hera at Olympia, following the German excavations and reconstructions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (1975 view)

Pietas and Polytheistic Heritage in Classical Rome

AS IN other fields, the Romans vastly elaborated these Greek themes. Rome’s relationship with Greece, however, was quite different from that of modern civilisation to classical antiquity. Certainly, Rome embraced not only Greek classical architecture but also Greek art-collecting. This had begun in the Hellenistic period with the Attalids and Pergamon, and influential Romans followed suit: beginning with the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC and culminating in the systematic plunder by the dictator Sulla (from 82 BC) and the corrupt governor Verres, a tradition became established of the accumulation of private collections of looted Greek art. Equally, Greek civilisation was seen as a model, to be admired and protected: under the rule of Augustus, the Athenian Agora was augmented by a 5th-century-BC Temple of Ares, relocated from Acharnai, and the Hellenophile, 2 nd-century-AD emperor Hadrian collected Greek art on a vast scale, especially in his Tivoli villa complex, and helped to preserve Greek cities themselves.7

But there was no sense of separation from Greece: its monuments were not seen as ‘historic’. Rome’s attitude to Greek religion was one of unstructured continuity; building on the same pantheon, they recognised a similar duty of self-interested respect to the world of the sacred, including gods and ancestors, a duty for which the Latin word was pietas. This meant something very different to its modern derivative, piety. The Latin equivalent of mnemeton, monumentum, carried the added overtone of warning, from monere, to warn. In the Roman world, a monument was a physical focus of pietas. The scope of the term was surprisingly wide, including not just statues or individual buildings but also ‘cultural property’ in almost a modern sense, including even entire towns. Monumentality in imperial Rome implied not only durable and imposing structures capable of evoking the past, but also a degree of sumptuousness that would perpetuate the fame of the patron and help uphold wider social norms and power structures.8

In Rome, with its driving sense of imperial mission, the public demands of pietas also encompassed the glorification of the city’s power and history, and of its ‘dignitas’ in general. The power of the empire and the emperors was bound up with the gods and their temples. The goddess Vesta in Rome was the goddess of hearth and home and the protector of the Roman nation. From the founding of the principate (imperial system) by Augustus at the end of the first century BC, there was an increasing shift towards an explicitly historical and secular approach to pietas, including ideas of continuity between past and future.

This was most explicitly articulated in literature, in the Aeneid, the epic written by the poet Virgil to exalt Rome’s destiny. Here, symbolic objects, and the pietas of the poem’s hero, are shown as bound up with the historicised future of the city, and the epic literary heritage of Greece and Homer is appropriated for the Roman cause. In Book 8, echoing the Iliad, Aeneas’ mother, the goddess Venus, gives him a special shield on which Vulcan had ‘wrought the story of Italy and the triumphs of Rome’, including, of course, those of Augustus; Aeneas looked in wonder at these scenes and then ‘lifted on to his shoulder the glory and destiny of his heirs’ (atollens umero famamque et fata nepotum). Earlier, in Book 6, he had witnessed in the underworld Rome’s unborn heroes, ‘souls of renown now awaiting life, who shall succeed to our name’ and build great cities ‘which are now nameless places, but whose names shall be famous one day’.9Although expressed in the semi-religious language of classical mythology and epic poetry, the Aeneid was actually a secular manifesto in all but name. We should remember its language of destiny, and of the conscious interrelationship of past and future, when tracing the dynamic ideologies of more recent centuries – including the Conservation Movement.

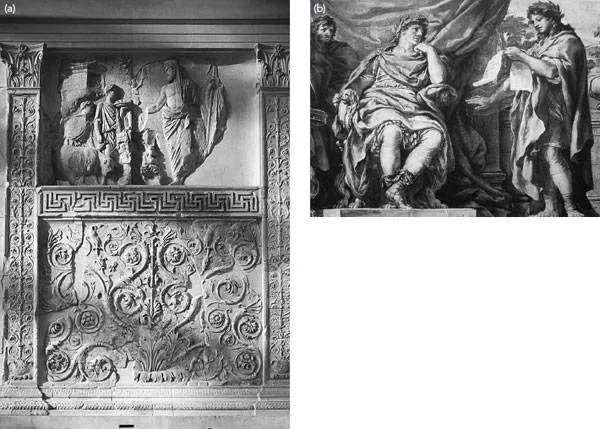

Figure 1.3 Public pietas in Augustan Rome

(a) The Ara Pacis, a monument to the peace secured by Augustus’s victories, was consecrated in 9 BC by the Senate. It was gradually recovered and excavated and, under fascism, incorporated in a purpose-designed pavilion by Vittorio Morpurgo (1938). This detail of the Ara Pacis shows Aene...