![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The title of this book, Reciprocal Frame Architecture, asserts that this is a book about architecture, but why ‘reciprocal frame’ architecture? What are ‘reciprocal frames’? The term means hardly anything, even to people who are in the field, like architects and engineers (unless they are already familiar with it for one reason or another). To ordinary people the name ‘reciprocal frame’ certainly does not mean much. This is perhaps one of the reasons for writing this book – to make reciprocal frame structures and the architectural forms they create better known.

Before talking about the opportunities that reciprocal frames offer, one has to start by defining the meaning of the title. From the name one can easily get the impression that the subject belongs to the field of frames, but then why ‘reciprocal’? Frames are a well-established structural system. What does ‘reciprocal’ signify when describing a structure and what kind of quality does it add to frame structure, if any at all? Also, what is the connection to architecture? What is ‘reciprocal frame architecture’?

We will start by defining the meaning of the terms used in the title, ‘reciprocal frame’ and ‘architecture’, and establish what they signify.

The reciprocal frame is a three-dimensional grillage structure mainly used as a roof structure, consisting of mutually supporting sloping beams placed in a closed circuit. The inner end of each beam rests on and is supported by the adjacent beam. At the outer end the beams are supported by an external wall, ring beam or by columns. The mutually supporting radiating beams placed tangentially around a central point of symmetry form an inner polygon. The outer ends of the beams form an outer polygon or a circle. If the reciprocal frame (RF) is used as a roof structure, the inner polygon gives an opportunity of creating a roof light.

The RF principle is not new and has been used throughout history, especially in the form of a flat configuration. This variation of the RF, where the beams are connected in the same plane forming a planar grillage, is presented in detail in Chapter 2. Flat grillages have typically been used for forming ceilings and floors when timbers of sufficient length were not available. Examples are the structures developed by Serlio, da Vinci, Honnecourt and others presented in Chapter 2. None of these designers, however, used the name ‘reciprocal frame’ for their structures.

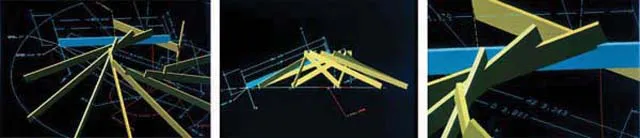

1.1 Typical RF structure – 3D view, elevation and detail.

The name ‘reciprocal frame’ comes from Graham Brown, who developed this type of structure in the UK. Graham used ‘reciprocal’ because of the way the beams mutually support each other.

In the Oxford English Dictionary the word ‘reciprocal’ has several meanings:

- Mathematical – so related to another that their product is unity

- Adjective – in return (for example, I helped him and he helped me in return).

In our context, it represents the appearance and behaviour of the unified structure in which each beam supports, and in turn is supported by, all of the others.

Because of the geometrical characteristics of the structure, the most appropriate forms of buildings (in plan) using the RF are circular, elliptical and regular polygonal. As a result, so far most of the buildings constructed using the RF have regular polygonal or circular plans. In the case of regular plan forms, all RF members are identical, which gives the possibility of modular RF construction.

The circular plan form was one of the first used. Many vernacular buildings throughout human history (mud huts, cave dwellings and so on) had approximately circular plan forms. They would appear to have a protective, womb-like quality. Also, circular and regular polygonal forms are typical in buildings of major significance, such as churches, concert halls, sports stadia, museums and the like.

If suitable materials are used for the main RF members, such as reinforced concrete, glued laminated timber, steel beams or trusses, the RF could span short and long distances with equal success. Because of the most common plan forms, polygonal and circular, the organization of the function and division of the internal spaces of the RF buildings are different from buildings with rectilinear plan forms. Since no internal supports are needed, the RF forms a very flexible architectural space. It is important to note that the beams that form the RF do not meet in a central point (as shown in Figure 1.1). This is different to most of the roof structures over buildings with circular plan forms, which have radial members meeting at the highest point of the roof.

On the other hand, since the inner and the outer polygons are defined by the end points of the beams, which can have different lengths, the RF can be used to cover almost any form in plan. The possibility of creating an infinite variety of plan forms, and at the same time incorporating different spans, makes it possible for the structure to be used on buildings with very different functions – indeed, for any function. Because the structure is not very well known, and despite its great potential, not many buildings using RFs have been constructed to date.

If one looks at the structures designed by Pier Luigi Nervi, the elegant shells designed by Heinz Isler or the great biomes of the Eden Project, it is evident that structural form defines architectural form to a great extent. The RF, although very different in scale to the mentioned structures, is similar in that it also influences architectural forms. The visual impact of the structure of self-supporting spiralling beams is very powerful. It clearly not only makes the buildings stand up, but affects how the spaces can be used as well as the overall architectural expression.

By varying the geometrical parameters of the RF structure, such as the length and number of beams, radii of inner and outer polygons and the beam slopes, a designer can achieve a great number of variations of the same structural system. In addition, one has the option of using single or multiple RF units (a combination of several single units), which adds to the versatility of the system and creates different architectural expressions.

Like any structural form, the RF structure has its limitations. There is no such thing as ‘the perfect structural solution’ and this book is not trying to present the RF as such. Rather, it will present the opportunities the RF offers, but also describe the most common challenges that arise.

The RF is still relatively unknown to most professionals and its architectural potential remains largely unexplored. This book therefore aims to bring the RF closer to designers, clients and users, making it a viable option in building design.

This book is structured in two parts. The first part (Chapters 1–5) looks at historical precedents, investigating possible morphologies (forms) that can be created with RFs, defining the geometrical parameters of the structure and its structural behaviour. The second part of the book presents the work of Japanese RF designers Kazuhiro Ishii, Yoichi Kan and Yasufumi Kijima, as well as British designer Graham Brown. Chapter 6 shows the context in which the Japanese RF buildings have emerged, while the case studies of reciprocal frame architecture (Chapters 7–10) show examples in which the RF structure and the architecture complement each other to form ‘reciprocal frame architecture’. Chapter 11 shows some additional recently built examples using RF structures.

Reciprocal frame architecture encompasses the work of many researchers and practitioners who have pushed the boundaries of what is possible in this field. The research and design work of John Chilton, pioneer in exploring the structural behaviour, geometry and morphology of RFs, is a valuable contribution. In addition, I also refer to the work of researchers Olivier Baverel, Messaoud Saidani, Joe Rizzuto, Vito Bertin and others, who have contributed to a better understanding of how these structures are configured and how they behave structurally.

The architectural work of designers Ishii, Kan, Kijima, Brown, Wrench, Adamson, Oesch and others shows what is possible in practice. Some of these designers who have contributed with their designs to reciprocal frame architecture have been able to demonstrate a real synthesis of structure and architecture, creating genuine architectural masterpieces.

It is hoped that this book will inspire the reader to learn more about the world of the reciprocal frame and how to use this amazing structure in creating new forms of architecture – reciprocal frame architecture.

![]()

2

BACKGROUND – THE

RECIPROCAL FRAME

HISTORICALLY

So who made the first reciprocal frame? Where did the idea come from? It would be difficult to find out when and where the first reciprocal frame (RF) was constructed; to do so would be like trying to establish when and where the first high-heeled shoe was produced, or when the first green wooden toy car was made. Perhaps these two would be easier to establish than the whereabouts of the first RF structures. There are two main reasons for this: the first is that very few people describe these structures as reciprocal frames; the second is that the idea is very old and the historic structures that adopted RF principles were mainly built of timber (well before steel and concrete were known to humankind), which deteriorated over the centuries or were lost in fires. Finding written documentation is not easy either, because of the absence of a common name for them.

Still, despite these difficulties which prevent us establishing where the first ideas about using structures like the RF originated, we can easily demonstrate that the RF principle has been around for many centuries.

Structures such as the neolithic pit dwelling (Figure 2.1), the Eskimo tent, Indian tepee (Figure 2.2) or the Hogan dwellings (Figure 2.3) have some similarities to the RF concept. Perhaps the latter two examples have greater similarities to the RF than the neolithic pit dwelling and the Eskimo tent. Similarly to the RF, the Indian tepee and the Hogan dwellings use the principle of mutually supporting beams. The differences between them and the RF are that the rafters forming the structure of the Indian tepee come together into a point where they are tied together and the integrity of the structure is secured in that way. Stretched animal skins provide additional stiffness to the conical form of the tepee. The animal skins have the role of the cladding roof panels used in RF structures, which in a similar way provide a ‘stretched skin effect’ and give additional st...