![]()

1

Introduction

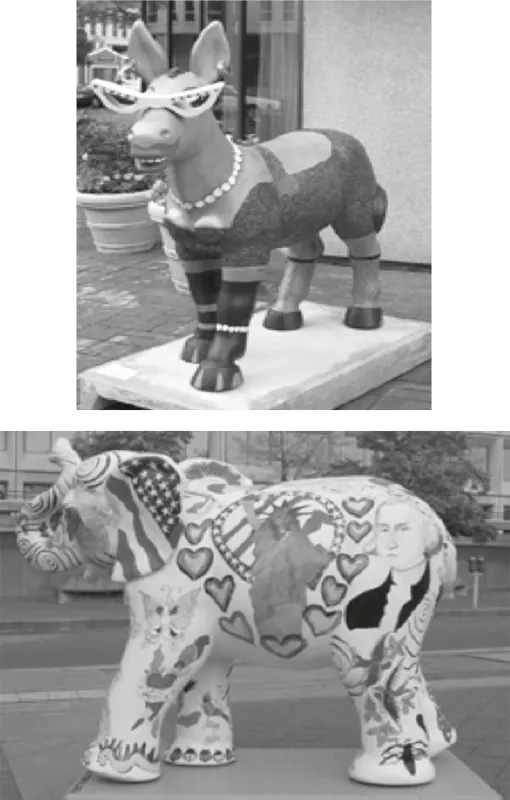

In the summer of 2002, the people of Washington DC and the United States were invited by First Lady Laura Bush to “Take a Party Animal Safari” in the nation’s capital. The Party Animals (see Figure 1.1), a public art project spearheaded by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, consisted of 100 donkeys and 100 elephants, referred to as “rounded, full canvasses upon which artists expressed themselves” (Gittens, Woo, McSweeney, & Stovall, 2002, p. 17). According to the Commission, the Party Animals were about having a passion for art, not politics. For the most part people in the community and tourists consumed these art pieces in this way referring to the animals as fun, imaginative and whimsical. To encourage participation in the Party Animals art project, invitations were sent to thousands of artists to submit designs. While selecting the 200 chosen ones, the DC Commission noted that they were not looking for political statements but rather they were looking for fine public art. The sculptures were then scattered throughout DC where tourists and DC residents could go on safari to find as many party animals as possible.

Figure 1.1 The Party Animals.

In the fall of 2002, an announcement was made that the university where Vivian was working would be hosting a number of the party animals on campus. At the time Vivian was teaching reading and language arts courses to potential elementary school teachers. With her colleague, Sarah Jewett, she capitalized on her students’ interest in the animals as an opportunity to have them re-read the sculptures from a critical literacy perspective.

What is powerful about this work, which is recounted in detail in Chapter 4, is the use of the students’ interests to create spaces for critical literacies in a university classroom. In teacher education classes and in professional development workshops for classroom teachers, focused on critical literacy and inquiry learning, participants are often reminded of the need to build curriculum using children’s inquiry questions, passions and interests. More than often they hear this message or they are asked to read articles and books about what this means. What we are suggesting in this book is that there is more we could do to help pre-service and in-service teachers understand critical literacy. Rather than limiting what we do to telling (lectures) or showing (providing examples from other people’s classrooms), we are suggesting giving them opportunities to experience firsthand what it is like to be a learner where the university teacher or workshop facilitator builds curriculum around their inquiry questions, passions and interests from a critical literacy perspective.

Living a Critically Literate Life

Negotiating Critical Literacies with Teachers is a demonstration of what it means to live a critically literate life. In particular this book puts on offer theoretical foundations and pedagogical resources for negotiating critical literacies in university or professional development settings as one way to help adult learners to not only learn about and frame their teaching from a critical literacy perspective but to help them live through or embody critical literacies that have importance in their own lives.

We wrote this book as a response to a gap in the literature on critical literacy and teacher education as well as teacher professional development. Specifically, this book speaks to what Dozier, Johnston and Rogers (2006) observe that as a profession we have not publicly articulated the nature of the alignment between our expectations for our own literate lives and our expectations for our students as literacy learners. This was reflected in the 1996 report of the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, which noted that “… universities often do not practice what they preach in terms of teaching …” (p. 3). More recently Cahnmann-Taylor and Souto-Manning (2010) point out that we, as a teaching profession, need to avoid simply, “talking the talk” (p. 7). Vivian and Sarah, in their work with the Party Animals attempted to avoid simply talking the talk but having their students live rather than read or hear about a critical literacy curriculum.

We offer this book as a demonstration of our practices in attempting to create spaces for our students and the teachers with whom we work to consider ways of taking up critical literacies in their own lives and in and outside of school. This includes the theoretical orientations that we use in not only teaching our students about critical literacy but how to be practitioners that live critically literate lives. Our goal is for our students, and those who take part in our professional development events to be able to participate differently in the world and to make the most informed decisions they could possibly make about important social issues. In turn we hope these teachers are able to take what they experience with us back to their own settings for use with the children with whom they work.

Our Stories/Our Selves

The three of us have come together based on a common longstanding interest in creating spaces for critical literacies in our own settings. Stacie is currently an Assistant Professor at American University. She is a former middle and secondary classroom teacher. Vivian is currently a Professor at American University. She is a former early childhood and elementary school teacher. Jerry is now Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, Bloomington. He has been working alongside teachers and advocating for teachers for over forty years. Our cumulative experience, spans from working in pre-school to graduate school settings; from teaching toddlers to doctoral students. Our teaching practice focuses on teaching literacy courses and leading professional development workshops, institutes, and seminars. The focus of this book is the theorized practice of critical literacies in our university classrooms and professional development settings with adult learners.

How this Book is Organized

Since the main premise of the book is on ways to help pre-service and in-service teachers understand what it means to take on a critical literacy perspective as a way of being rather than as a set of activities, we thought it would be important for us to build into this text opportunities for you to engage with critical literacies yourselves. As such throughout the book we have included various points for reflection and discussion. These come in the form of reflection points, try this pedagogical strategies, and resource boxes.

Reflection Point

Each reflection point focuses on a topic or issue. Some of these are set up as scenarios or contexts for you to discuss and think about. Others are set up as a series of questions for you to consider.

Try This: Pedagogical Strategy

These take the form of invitations or activities to try in your setting, or narratives describing a particular engagement or strategy for taking up critical literacies in various contexts.

Resource Box

These are collections of texts that focus on a particular topic or issue. Some of these boxes are meant for use in professional development settings while others are materials such as text sets for use in classroom settings.

In order to make clear the theoretical positions from which we have written this book, in Chapter 2, “Negotiating Spaces for Critical Literacy in the 21st Century,” we outline various theoretical positions and learning theories that can inform a critical literacy curriculum, including inquiry learning and other socio-cultural theories. We also include a beginning set of principles that might guide curriculum as we go about developing a more critically literate citizenry for the 21st century. In addition, as a way to make visible the life experiences that impact who we are, what we believe and our teaching practice, we have include author biographies at the end of Chapter 8, “Teaching and Living Critical Literacies.” There we offer you a narrative account of some of our past experiences to give you a sense of the position(s) from which we speak and engage in the practice of teaching.

According to bell hooks (1994) teaching should be a career that engages not only the student but also the teacher. In Chapter 3, “Outgrowing Our Current Selves: It’s Not Just a Job—It’s a Lifestyle,” we explore what it means to outgrow our current selves. In particular we focus on how the development and use of a teaching philosophy can help educators unpack their Discursive practices and the ideological positions through which they engage in the practice of teaching. These of course are the same positions through which they interpret their students’ learning. Following this, in Chapter 4, “Building Curriculum Using Students’ Interests,” we pick up from where this introductory chapter began and further unpack what happened as space was created in Vivian’s literacy methods class for her students to read the Party Animal sculptures from a critical literacy perspective. Their critical readings helped make visible the complexities, patterns, trends, particularities, generalities, and/or discrepancies, in the information conveyed on the sculptures. In Chapter 5, “Challenging Commonplace Thinking,” we share instances of working with children’s literature and everyday text such as print ads to disrupt the commonplace viewpoints. In this chapter we share examples of capitalizing on our students’ interest in children’s literature or adolescent novels as a jumping off point for constructing critical literacies in the tertiary classroom or workshop setting. This includes having participants re-design existing texts and creating counter-narrative texts or alternate version texts that disrupt the ideologies and dominant ideas that surround us. In the following chapter, “Interrogating Multiple Perspectives,” we continue working with children’s literature to explore possibilities for imagining the world from the perspective of others. This time however we focus heavily on the use of text sets or multiview texts. These are combinations of texts that offer complimentary or conflicting accounts of the same topic issue or event. In the chapter we talk about the ways in which multiple perspectives complicate what we know and thus complicate curriculum making for a much more sophisticated, powerful and pleasurable experience for our students.

Chapter 7 focuses on technology and media literacy. In this chapter we will talk about the possible relationship(s) between critical literacy and media studies by asking questions such as the following:

- What does new media afford our practice?

- Using technology, what can we do differently?

- Using technology, what can we do in new ways?

Also included in this chapter are examples of classroom explorations of critical literacy and media technology we share with our students and the teachers with whom we work.

In Chapter 8 we gather together final thoughts and set up a discussion on ways forward with regards to engaging with critical literacies as lived experiences with adult learners in pre-service or in-service settings. We share insights that tie together each of the chapters and in so doing lay down a course for future agendas. We argue for why education has to be more than rhetoric and that in order to be effective, learners need to take on new identities and new agency. We then discuss the notion that it is supporting the transformation of our selves and our world that needs to be the focus of curricular work in the future.

Education and Changing Culture

Education, like literacy, is never innocent. Even further, it is always about change, and even more specifically, cultural change. While one can argue that education should preserve culture, in reality education has always been about changing culture. The trick, we suppose, is to continually re-visit and re-think what we are doing. So, too, with literacy. We will conclude this introduction by arguing that together teachers and students need to explore how critical practices such as making social statements and taking social action can become a social practice embedded in classrooms of the 21st century because the future, after all, is ours for the making.

![]()

2

Negotiating Spaces for Critical Literacy in the 21st Century

Carole Edelsky (1999) suggests that most of us have little or no conscious awareness of the socio-political systems of meaning that are operating and the power relationships that are involved in what it is we teach. She believes that educators at all levels need to negotiate spaces for critical literacy in their classrooms.

Reflection Point 2.1

Current Understanding of Critical Literacy

- What is your current understanding of critical literacies?

- Say something about what you think of Edelsky’s belief that educators at all levels should negotiate spaces for critical literacy in their classrooms.

Finding a Frame: Critical Literacy and Teacher Education—Why Does it Matter?

Although they don’t use the term “critical literacy,” Westheimer and Kahne (2004) describe a range of political commitments associated with educating for democracy. We have found their focus on citizenship as a frame for understanding curriculum very helpful in illuminating various notions of critical literacy. They begin with the definition of a “Personally Responsible Citizen.” Such citizens, they tell us: (1) Act responsibly in their community; (2) Work and pay taxes; (3) Obey laws; (4) Recycle and give blood; and (5) Volunteer to lend a hand in times of crisis. Given the problem of hunger in the community, for example, personally responsible citizens are willing to contribute their share to a food drive.

The next group they describe are “Participatory Citizens.” From a critical perspective, participatory citizens do more than participate since they: (1) Take charge and organize community efforts; (2) Know how governments work; and (3) Implement strategies for accomplishing collective tasks. Given hunger as a problem in the community, participatory citizens would be the ones who would organize and lead the food drive.

Another citizenry that Westheimer and Kahne describe is labeled as “Justice-Oriented.” Justice-oriented citizens: (1) Critically assess social, political, and economic structures to see beyond surface level causes; (2) Seek out and address areas of injustice; and (3) Know about democratic social movements and how to effect systemic change. In terms of responding to hunger as a community problem, justice-oriented citizens research why people don’t have enough food and take social action to address root causes.

What is important about Westheimer and Kahne’s model is that it stresses going beyond the surface structure of issues. When critical literacy is addressed in schools, we often stop at the level of a food drive or organizing a community campaign to collect money to fill a food pantry. While these are noble efforts, Westheimer and Kahne remind us that as educators, we should not be satisfied t...