![]()

Chapter 1

From Bohemia to the End of the World

Bohemia’s lack of a coastline did not keep Czechs from participating in one of the great features of the history of early modern Europe—long-distance travel. It is true that they were only involved with the voyages of exploration through reading authors like Amerigo Vespucci, who was translated and published in Czech in 1506. But this did not mean that long-distance travel was beyond them. The most common types of Czech travelers who journeyed outside of Central Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land and imperial administrators accompanying political embassies. In the second half of the seventeenth century, the sons of noble families started taking the Grand Tour through Western and Mediterranean Europe. When these travelers returned home, many joined another trend popular across early modern Europe and wrote about their adventures. The travelogues were not only widely read in their own time, but some of them are counted today among the masterpieces of early Czech literature. While Czechs enjoyed reading about the travels of Mandeville and Marco Polo as much as Western Europeans, they also had their own indigenous canon of travelers and famous journeys. These travelogues are full of valuable evidence about the worldviews of Czechs during this period.

One of these storied Czech journeys took place in 1465, when the Hussite King Jiří z Poděbrad sent out an emissary to the major heads of state of Western Europe. Jiří had been excommunicated and was hoping to find support for his rule, or at least someone to intercede for him with the Pope. The embassy set out from Prague and traveled down the Rhine, through the Low Countries, England, France, the Iberian Peninsula, and northern Italy before returning home, unsuccessful. Inspired by the struggle of Hussite Bohemia to achieve recognition in the rest of Europe, the fin-de-siècle nationalist writer Alois Jirásek used the travelogues to write a historical novel about this mission, called From Bohemia to the End of the World. The title alludes to the westernmost section of the journey, when the embassy followed part of the pilgrims’ trail to Compostela. They spent some time at Cape Finisterre, known at the time as Finis Terrae or literally “the end of the world.”

Jirásek’s novel starts with a young boy asking an old man whether it was really true that he had been to the end of the world. The old traveler then begins to tell his grandchildren the story of Jiří z Poděbrad’s embassy. When he reaches the episode at Finisterre, he affirms that this was the “final end of the world” and embellishes this statement with, “That is the end of solid land, the end of the world, for farther on there is nothing but sea and more sea, and where the end of that is, only dear God himself knows such a thing.”1 This romantic view of Finisterre is an only slightly exaggerated form of the original text, which explains that the village there is named Finis Terrae “because past it there is nothing other than water and wide seas, whose borders no one knows except God himself.”2A German chronicler who was also a member of this expedition added that “some had tried to find out what was beyond and had sailed with Galleys and ships, but not one of them returned.”3 Though Jirásek the novelist’s larger goal is to dramatize the plight of Hussite Bohemia, what seems to have captured his imagination in this story is the way in which the travelers constructed their world. His title and the organization of the novel come from the idea that, in the minds of the travelers, they had journeyed both literally and imaginatively from Bohemia to the end of the world.

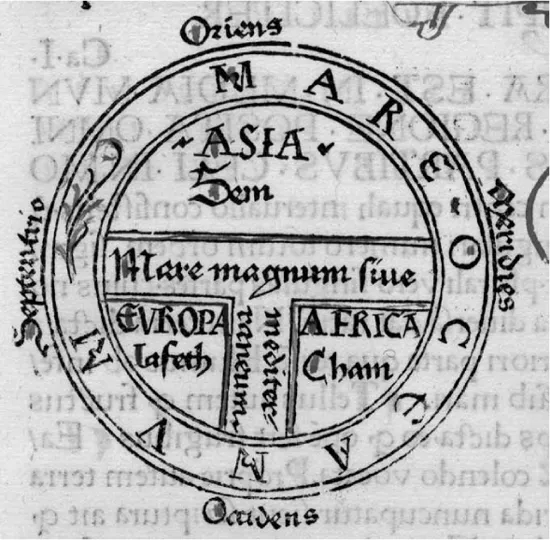

This book is more concerned with travelers who went the opposite direction—with those who went to the heart of the world, rather than its western edge—but is equally interested in the ways in which travel writers construct their worldviews. According to one of the most common cartographic traditions in medieval and early modern Europe, called the T-O type of map, these “cartefacts” were oriented (literally) toward the east, rather than the north, typically with Jerusalem at the center. The first printed map in Europe was drawn in this style. It appeared in a 1472 edition of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae (Figure 1.1).4 This means that, to the early modern mind, travelers to Istanbul or to the Holy Land may have been traveling toward the center of the world, while travelers to the western coast of Iberia would be going to its end.

Travel writing has much in common with map-making, and some of the scholarship on cartography applies equally well to travel narratives. Following the lead of Brian Harley, Denis Cosgrove defines mapping as a signifying process, as “creative, sometimes anxious, moments in coming to knowledge of the world ….” Cosgrove continues to say that the map is then both the “spatial embodiment of knowledge and a stimulus to further cognitive engagements.”5 This description of the mapping process could also serve as an apt description for travel and travel writing. Rather than the spatial embodiment of the map, the travelogue is a linguistic representation of that creative and often anxious moment of encounter and discovery. One of the jobs of the travel writer is to categorize and organize geographic knowledge, to tell the reader what is out there and how it fits into a general picture of the world.

Figure 1.1 T-O type map of the world, from a 1472 edition of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae

This aspect of travel writing will be the focus for the following chapter. It will compile and examine writing from Czech travelers to or through the Islamic world in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. It will analyze the representations of space, distance, and proximity in these travelogues in order to outline a variety of Czech worldviews in this period. Rather than being interested solely in the place of the Islamic world on these mental maps, it will also analyze the spatial relationship between the Islamic world and the Czech lands in these texts by focusing on representations of boundaries and depictions of distance and proximity. The pictures that result are more complicated than a model of the Czechs as the easternmost edge of Europe or as an antemurale Christianitatis. Writing about travel also gave Czechs the opportunity to locate themselves at the center of their own world, rather than at the periphery of someone else’s.

Of course, geographic knowledge is not the only type of knowledge communicated by the traveler. This book is going to use two separate chapters to discuss issues that are necessarily intertwined—the travelers’ attitudes toward the space traveled through and the travelers’ attitudes toward the people and cultures encountered. The two are necessarily experienced simultaneously and are written about in the same texts. The travel writer simultaneously structures and relates geographic and ethnographic knowledge to the reader. Many of the same authors will then appear in multiple chapters, but in order to concentrate fully on each aspect of travel writing, this chapter will deal primarily with issues of space and geography and the following chapter will examine ethnography, similarity, and difference.

Much of the secondary literature on travel writing has been more concerned with its ethnographic aspect—with the encounters and interactions between different cultures—rather than with space, distance, and proximity. Scholars have seen in the writing about these encounters a range of significant developments, including the evolution of modern subjectivity, the rise of empiricism, and the development of imperialism.6 In recent scholarship, the travel component in travel writing seems to have become less important. This is interesting when discussing early modern travel, because it is the travel itself (whether real or fictional) that gave travelogues authority in the eyes of their readers.7 The travel writer derived the authority to construct and represent foreign places from having viewed, as Nicolas de Nicolay wrote in 1585, “the very things themselves,” an act that could only be performed by leaving traditional centers of power and authority within Europe to journey to the periphery.8

The act of travel not only gives travel writers their authority, but also alters how they construct space, transforming it from static to dynamic. In his essay “Spatial Stories,” Michel de Certeau makes a distinction between place and space, calling space a “practiced place.” The distinction for him is that a “space exists when one takes into consideration vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables … Space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function in a polyvalent unity of conflictual programs or contractual proximities.”9 For de Certeau, space is more than just location. It is necessarily constructed in relation to other spaces, to other times, and with a sense of possible movement to and through.

This is the type of space that the traveler constructs in a travelogue. Jerusalem, for example, is never just a place in and of itself, but also is a certain distance from other sites, is a certain length of journey from the last place visited, is seen in relation to the Biblical Jerusalem, and is brought into a relation of one sort or another with the traveler’s home, whether a relation of distance and difference or proximity and familiarity. This definition of space helps us to think about how descriptions of foreign sites always also shed light on the traveler’s relationship to home. In the travelogues in this chapter, ideas of home and connections to the Czech lands often accompany descriptions of the Islamic world.

The traveler also creates borders in order to construct and organize the space through which he moves. In the classic Orientalism, Edward Said discusses how cultures differentiate their own space from foreign space. One of the key steps in creating an imaginative geography is to divide “our” space from “their” space, which is a “way of making geographical distinctions that can be entirely arbitrary.”10 Early modern travelogues are full of boundaries and markers of transition between separate spaces, but also evidence that borders could be crossed. As Tom Betteridge noted in his introduction to Borders and Travellers in Early Modern Europe, early modern Europe was “obsessed with” both creating and transgressing borders. Early modern Europeans “found, imagined and manufactured new borders for its travelers to cross,” while at the same time they “operated as if existing borders were simply there to be crossed and erased.”11 Just as the travelogues in this chapter chart difference and draw boundaries, they also make connections and erase borders.

The essence of writing about travel involves constructing and representing the space through which the journey has moved. Those spatial descriptions then testif...