eBook - ePub

The History of Southern Africa

Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The History of Southern Africa

Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The history of southern Africa is marked by both the convergence and divergence of diverse cultures. Clashes between European settlers and indigenous peoples throughout this section of the continent were common. At stake were rights to a wealth of natural resources and, as time went by, independence. This volume surveys the often volatile histories of each country in the region and introduces readers to the diversity of peoples that are an important element of each country's past and future.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The History of Southern Africa als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The History of Southern Africa von Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus History & African History. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

HistoryThema

African HistoryCHAPTER 1

EARLY HISTORY

Southern Africa comprises the countries of Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The history of Southern Africa cannot be written as a single narrative, as shifting geographic and political boundaries and changing historiographical perspectives render this impossible. Research into local history in the late 20th and early 21st century has presented fragmented historical knowledge, and older generalizations have given way to a complex polyphony of voices as new subfields of history—gender and sexuality, health, and the environment, to name but a few—have developed. Archaeological and historical inquiry has been extremely uneven in the countries of the Southern African subcontinent, with Namibia the least and South Africa the most intensely studied. Divided societies produce divided histories, and there is hardly an episode in the region’s history that is not now open to debate. This is as true of prehistory as of the more recent past.

The uncertainties of evidence for the long preliterate past—where a bone or potsherd can undermine previous interpretations and where recent research has subverted even terminology—are matched by conflicting representations of the colonial and postcolonial periods. In Southern Africa, history is not a set of neutrally observed and agreed-upon facts. Present concerns colour interpretations of even the remote past. For all the contestants in contemporary Southern Africa there has been a conscious struggle to control the past in order to legitimate the present and lay claim to the future. Who is telling what history for which Africa is a question that needs constantly to be addressed.

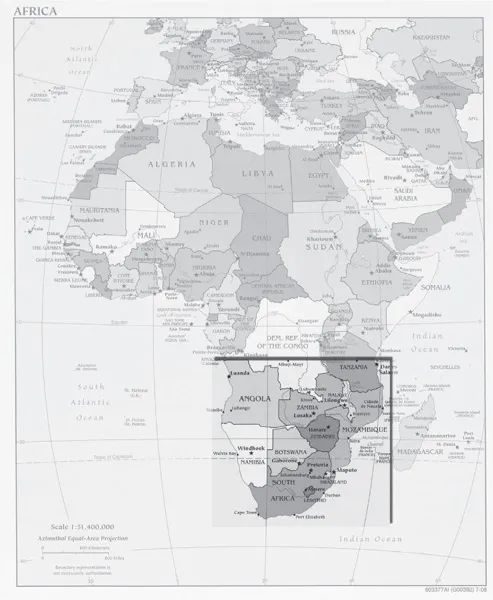

Map of Africa, emphasizing the countries of Southern Africa. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

EARLY HUMANS AND STONE AGE SOCIETY

The controversies in Southern African history begin with the discovery of a fossilized hominin skull in a limestone cave at Taung near the Harts River north of Kimberley in 1924, followed in 1936 by discoveries in similar caves in the Transvaal (now Limpopo and Gauteng provinces) and Northern Cape province, in South Africa. Other significant hominin finds were made in the Sterkfontein Valley (in Gauteng province) beginning in the 1940s. For some time the significance of these finds and their relationship to the evolution of early humans were unappreciated, perhaps because the finds could not be dated, and stone tools—long regarded as the defining characteristic of early humans—had not been found with them.

Since that time, similar but datable discoveries in eastern Africa as well as discoveries in the Makapansgat Valley in South Africa have made it possible to place the South African remains in sequence and identify them as australopithecines, upright-walking creatures who are the earliest human ancestors. The australopithecines who roamed the highland savanna plains of Southern Africa date from about 3 million to 1 million years ago. There can be little doubt that for hundreds of thousands of years Southern Africa, like eastern Africa, was in the forefront of human development and technological innovation.

Controversies remain, however. The connections between australopithecines and earlier potentially hominin forms remain unclear, while a number of species of australopithecines have been identified. Their evolution into the species Homo habilis and then into the species Homo erectus—which displayed the larger brain, upright posture, teeth, and hands resembling those of modern humans and from whom Homo sapiens almost certainly evolved—is still fiercely debated. Homo erectus appears to have roamed the open savanna lands of eastern and Southern Africa, collecting fruits and berries—and perhaps roots—and either scavenging or hunting. Acheulean industry appeared during the Early Stone Age (c. 2.5 million to 150,000 years ago) and was characterized by the use of simple stone hand axes, choppers, and cleavers. First evident about 1.5 million years ago, it seems to have spread from eastern Africa throughout the continent and also to Europe and Asia during the Middle Pleistocene Epoch, reaching Southern Africa about 1 million years ago. Acheulean industry remained dominant for more than 1 million years.

During this time early humans also developed those social, cognitive, and linguistic traits that distinguish Homo sapiens. Some of the earliest fossils associated with Homo sapiens, dated from about 120,000 to 80,000 years ago, have been found in South Africa at the Klasies River Mouth Cave in Eastern Cape province, while at Border Cave on the South Africa–Swaziland border a date of about 90,000 years ago has been claimed for similar Middle Stone Age (150,000 to 30,000 years ago) skeletal remains.

With the emergence of Homo sapiens, experimentation and regional diversification displaced the undifferentiated Acheulean tool kit, and a far more efficient small blade (also called microlithic) technology evolved. Through the controlled use of fire, denser, more mobile populations could move for the first time into heavily wooded areas and caves. Wood, bark, and leather were used for tools and clothing, while vegetable foods were also probably more important than their archaeological survival suggests.

Some scholars believe that the addition of organized hunting to gathering and scavenging transformed human society. The large number of distinctive Late Stone Age (30,000 to 2,000 years ago) industries that emerged reflect increasing specialization as hunter-gatherers exploited different environments, often moving seasonally between them, and developed different subsistence strategies. As in many parts of the world, changes in technology seem to mark a shift to the consumption of smaller game, fish, invertebrates, and plants. Late Stone Age peoples used bows and arrows and a variety of snares and traps for hunting, as well as grindstones and digging sticks for gathering plant food. Using hooks, barbed spears, and wicker baskets, they also were able to catch fish and thus exploit rivers, lakeshores, and seacoasts more effectively.

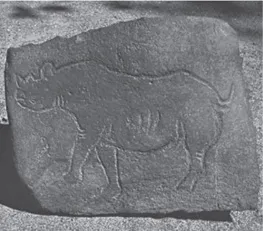

Engraving of a rhinoceros, an example of San rock painting and engraving in South Africa. Courtesy of A.R. Willcox; photograph.

Despite the ever-increasing number of radiocarbon dates available for the many Late Stone Age sites excavated in Southern Africa, the reasons for changed consumption patterns and variations in technology are poorly understood. Until the 1960s, population explosion and migration were the common explanations; subsequent explanations have stressed adaptation. Yet the reasons for adaptation are equally unclear and the model equally controversial. Environmental changes do not seem to have been directly responsible, while the evidence for social change is elusive. Nevertheless, the appearance of cave art, careful burials, and ostrich-eggshell beads for adornment suggests more sophisticated behaviour and new patterns of culture. These developments apparently are associated with the emergence between 20,000 and 15,000 BCE of the earliest of the historically recognizable populations of Southern Africa: the Pygmy, San, and Khoekhoe peoples, who were probably genetically related to the ancient population that evolved in the African subcontinent.

Although many scholars attempt to deduce the nature of Late Stone Age societies by examining contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, this method is fraught with difficulties. Evidence from Botswana and Namibia suggests that many contemporary hunter-gatherers recently have been dispossessed and that their present way of life, far from being the result of thousands of years of stagnation and isolation, has resulted from their integration into the modern world economy. This hardly provides an adequate model for reconstructions of earlier societies.

During historic times hunter-gatherers were organized in loosely knit bands, of which the family was the basic unit, although wider alliances with neighbouring bands were essential for survival. Each group had its own territory, in which special importance was attached to natural resources, and in many instances bands moved seasonally from small to large camping sites, following water, game, and vegetation. Labour was allocated by gender, with men responsible for hunting game, women for snaring small animals, collecting plant foods, and undertaking domestic chores. These patterns are also evident in the recent archaeological record, but it is unclear how far they can be safely projected back.

Contrary to the popular view that the hunter-gatherer way of life was impoverished and brutish, Late Stone Age people were highly skilled and had a good deal of leisure and a rich spiritual life, as their cave paintings and rock engravings show. While exact dating of cave paintings is problematic, paintings at the Apollo 11 Cave in southern Namibia appear to be some 26,000 to 28,000 years old. Whereas the art in the northern woodlands is stylized and schematic, that of the savanna and coastlands seems more naturalistic, showing scenes of hunting and fishing, of ritual and celebration. The latter vividly portrays the Late Stone Age cosmology and way of life. The motives of the artists remain obscure, but many paintings appear linked to the trance experiences of medicine men, in which the antelope (eland) was a key symbol. In later rock paintings there is also the first hint of the advent of new groups of herders and farmers.

THE KHOISAN

In the long run these new groups of herders and farmers transformed the hunter-gatherer way of life. Initially, however, distinctions between early pastoralists, farmers, and hunter-gatherers were not overwhelming, and in many areas the various groups coexisted. The first evidence of pastoralism in the subcontinent occurs on a scattering of sites in the more arid west. There the bones of sheep and goats, accompanied by stone tools and pottery, date to some 2,000 years ago, about 200 years before iron-using farmers first arrived in the better-watered eastern half of the region. It is with the origins of these food-producing communities and their evolution into the contemporary societies of Southern Africa that much of the precolonial history of the subcontinent has been concerned.

When Europeans first rounded the Cape of Good Hope, they encountered herding people, whom they called Hottentots (a name now considered pejorative) but who called themselves Khoekhoe, meaning “men of men.” At that time they inhabited the fertile southwestern Cape region as well as its more arid hinterland to the northwest, where rainfall did not permit crop cultivation, but they may once have grazed their stock on the more luxuriant central grasslands of Southern Africa. Linguistic evidence suggests that the languages of the later Khoekhoe (the so-called Khoisan languages) originated in one of the hunter-gatherer languages of northern Botswana. In the colonial period, destitute Khoekhoe often reverted to a hunter-gatherer existence. Herders and hunters were also frequently physically indistinguishable and used identical stone tools. Thus, the Dutch, and many subsequent social scientists, believed they belonged to a single population following different modes of subsistence, including hunting, foraging, beachcombing, and herding. For this reason the groups are often referred to as Khoisan, a compound word referring to Khoekhoe and San, as the Nama called hunter-gatherers without livestock (Bushmen, in the terminology of the colonists, is now considered pejorative).

The archaeological remains of nomadic pastoralists living in impermanent polities are frustratingly sparse, but in the upper Zambezi River valley, southwestern Zimbabwe, and Botswana, herding and pottery appear late in the 1st millennium BCE. Cattle and milking appear somewhat later than small stock and were perhaps acquired from iron-using farmers in western Zimbabwe or northeastern South Africa. The loosely organized herders expanded rapidly, driven by their need for fresh grazing areas. Along with pastoralism and pottery came other signs of change: domestic dogs, changes in stone tool kits, altered settlement patterns, larger ostrich-eggshell beads, and the appearance of marine shells in the interior, which suggests the existence of long-distance trade.

Most of Southern Africa’s early agricultural communities shared a common culture, which spread across the region remarkably quickly from the 2nd century CE. By the second half of the 1st millennium CE, farming communities were living in relatively large, semipermanent villages. They cultivated sorghum, millet, and legumes and herded sheep, goats, and some cattle; made pottery and fashioned iron tools to turn the soil and cut their crops; and engaged in long-distance trade. Salt, iron implements, pottery, and possibly copper ornaments passed from hand to hand and were traded widely. Some communities settled near exceptionally good salt, metal, or clay deposits or became known for their specialist craftsmen.

THE SPREAD OF BANTU LANGUAGES

Archaeolo...