eBook - ePub

Analyzing Electoral Promises with Game Theory

Yasushi Asako

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 112 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Analyzing Electoral Promises with Game Theory

Yasushi Asako

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Electoral promises help to win votes and political candidates, or parties should strategically choose what they can deliver to win an election. Past game-theoretical studies tend to ignore electoral promises and this book sheds illuminating light on the functions and effects of electoral promises on policies or electoral outcomes through game theory models. This book provides a basic framework for game-theoretical analysis of electoral promises. ?

The book also includes cases to illustrate real life applications of these theories. ?

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Analyzing Electoral Promises with Game Theory als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Analyzing Electoral Promises with Game Theory von Yasushi Asako im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Política y relaciones internacionales & Campañas políticas y elecciones. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1 Electoral promises in formal models

1.1 “Read my lips, no new taxes” and “end welfare as we know it”

Before an election, candidates announce platforms and the winner implements a policy after the election. Although politicians usually betray their platforms, such betrayal could prove costly. For example, in 1988 in the United States, George H. W. Bush promised, “read my lips, no new taxes.” However, he increased taxes after becoming president. The media and voters noted this betrayal, and he lost the 1992 presidential election (Campbell, 2008, p. 104). On the contrary, in his 1992 campaign, Bill Clinton promised to “end welfare as we know it.” In the 1994 midterm election, the Republican Party gained a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Under pressure from Congress to keep his platform, he signed the welfare reform bill in 1996 (Weaver, 2000, Ch. 5).

These cases show two of the major characteristics of electoral promises. First, politicians decide policy on the basis of their platforms and the perceived cost of betrayal. If politicians betray their platforms, the people and media criticize them, they must address their electorate’s complaints, their approval ratings may fall, and the possibility of them losing the next election might increase – as in the case of Bush.1 Moreover, a stronger party or Congress may discipline such politicians, as in the case of Clinton.2 On the basis of such costs of betrayal and the platform, the winner decides on the policy to be implemented after the election. The second characteristic is that politicians frequently prefer to use vague words and announce several policies in their electoral promises, a practice referred to as “political ambiguity.” For instance, Clinton’s promise above only stated his intention to reform the welfare system; he did not explicitly reveal the nature of the reform, which left the door open for further negotiation with the Republican Party.

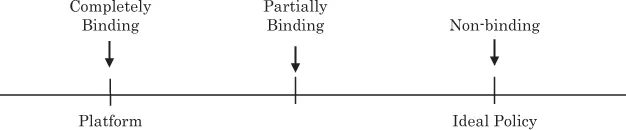

However, most game-theoretical analyses of electoral competition have overlooked these two characteristics of electoral promises. Indeed, they avoid explicitly analyzing electoral platforms altogether. Formal models have supposed that candidates can choose only a single policy, meaning that political ambiguity never arises. Moreover, they fail to analyze platforms and policies separately and instead introduce two polar assumptions about platforms. On the one hand, models with completely binding platforms suppose that a politician cannot implement any policy other than the platform. That is, a politician never reneges on his/her promise and automatically implements the announced platform. The most famous example of such models is the electoral competition models in the Downsian tradition, that is, models based on those proposed by Downs (1957) and Wittman (1973). On the other hand, models with non-binding platforms suppose that a politician can implement any policy freely without any cost. In these models, voters do not believe electoral promises, so it is not meaningful to announce them. Therefore, a candidate’s decisions on his/her platform are not explicitly analyzed. For example, this approach is taken in citizen-candidate models (Osborne and Slivinski, 1996; Besley and Coate, 1997) and retrospective voting models (Barro, 1973; Ferejohn, 1986; Besley, 2006). Neither model captures how, for example, Bush betrayed his platform and was then punished for doing so by the electorate or how Clinton kept his platform under pressure from Congress. To consider the effects of platforms on political competition, it is thus important to bridge these two settings; as Persson and Tabellini (2000) indicate, “(it) is thus somewhat schizophrenic to study either extreme: where platforms have no meaning or where they are all that matter. To bridge the two models is an important challenge” (p. 483).

The main purpose of this book is to provide a theoretical framework within which to analyze these two characteristics of campaign promises based on the electoral competition model in the Downsian tradition. Chapters 2 and 3 build a model with partially binding platforms, which supposes that although a candidate can choose any policy, there is a cost of betrayal. The policy to be implemented is affected by, but may be different from, the platform because this cost of betrayal increases with the degree of betrayal. As Figure 1.1 shows, models of completely binding platforms assume that candidates implement their platform, whereas models of non-binding platforms assume that candidates implement their own ideal policy. On the contrary, models of partially binding platforms suppose that candidates implement a policy situated between their platform and ideal policy. Chapter 4 discusses why candidates make vague promises in electoral competitions. Classically, the convexity of a voter’s preference is recognized as one possible reason driving political ambiguity. However, past studies have not shown it as an equilibrium. Based on the foregoing, I identify the conditions under which candidates choose an ambiguous platform in the equilibrium when voters have convex utilities. Chapters 2 to 4 are revised versions of Asako (2015a, 2015b, 2019), respectively. The proofs of all the propositions, lemmas, and corollaries are collected in the appendix.

Figure 1.1 Completely, Non-, and Partially Binding Platforms.

1.2 Contributions and implications

The main contribution of this book is to show that the implications change considerably from past studies when electoral promises are explicitly analyzed in formal models. In particular, this book introduces two major characteristics of electoral promises, namely, partially binding platforms and political ambiguity, into the standard political competition model (Downs, 1957; Wittman, 1973). These new models can explain many aspects of real elections that cannot be predicted by previous frameworks. The findings confirm the importance of analyzing electoral promises explicitly using game theory.

The remainder of this chapter summarizes these new findings and explains how they differ from those of previous models.

1.2.1 Two roles of electoral promises

Because of the cost of betrayal, electoral promises serve as a commitment device and as a signal (see Chapters 2 and 3, respectively). First, because of the cost of betrayal, voters may believe that politicians will not betray their promise so severely to avoid paying this cost, and hence platforms can be considered as partial commitment devices to restrict a candidate’s future policy choice. Second, because of the cost of betrayal, candidates do not have an incentive to choose a platform further away from their preferred policy. This is because the winner will betray the promise severely and pay large costs when his/her platform differs substantially from his/her ideal policy. Therefore, voters may be able to predict the position of the candidate’s preferred policy through electoral promises. Thus, platforms can work as a signal about the candidate’s policy preference. The following subsections summarize the main implications of each chapter.

1.2.2 Electoral promises as a commitment device

Chapter 2 mainly analyzes electoral promises as a commitment device by introducing the cost of betrayal into the Downsian electoral competition model with policy-motivated candidates. This model is generally known as Wittman’s (1973) model. There is a one-dimensional policy space, and voters’ preferred policies are distributed on this space. The preferred policies of 50% of voters are located to the left of the median policy and the remaining 50% of voters’ preferred policies are located to the right. A voter who prefers the median policy is called the median voter.

One candidate prefers to implement a policy to the left of the median policy and the other candidate, to the right. Candidates announce their platforms before the election and the winner chooses a policy to be implemented thereafter. Politicians care about (1) the probability of winning, (2) the policy to be implemented, and (3) the cost of betrayal. I also analyze endogenous decisions to run on the basis of a simplified version of the citizen-candidate model (Osborne and Slivinski, 1996).

Partially binding platforms can explain the following observations from real elections, which cannot be explained by models of completely binding or non-binding platforms. Usually, in real elections, candidates have asymmetric characteristics (e.g., their policy preferences, the importance of policy, and costs of betrayal differ). Moreover, we frequently observe asymmetric outcomes (i.e., one candidate has a higher probability of winning than the other). Some candidates may avoid compromising on their principles to please voters and accept a lower probability of winning than their opponent, even though their probability of winning would be higher by compromising.

However, in existing frameworks, it is difficult to show asymmetric electoral outcomes. In models of completely binding platforms, both candidates propose the median voter’s ideal policy regardless of their characteristics; hence, they have the same probability of winning (50%). In models of non-binding platforms, voters expect candidates’ ideal policies to be implemented if they win. Then, only the candidate whose ideal policy is closer to the median policy can win, and no other characteristics affect the electoral outcome. On the contrary, in models of partially binding platforms, candidates with asymmetric characteristics can and will choose different platforms and policies to be implemented, since if their characteristics differ, one candidate may have a greater incentive to win – and would actually win – the election. This results in an asymmetric electoral outcome. Chapter 2 shows that an electoral outcome is asymmetric in the equilibrium when two candidates have different characteristics. For example, a more moderate candidate whose ideal policy is closer to the median policy wins against a more extreme candidate. Although this implication is the same as in models of non-binding platforms, this outcome is derived endogenously as opposed to exogenously as in those models. Similarly, if a candidate’s cost of betrayal is higher than that of his/her opponent with the same degree of betrayal, the former candidate wins. If the cost is lower with the same degree of betrayal, a candidate will betray his/her platform more severely such that the realized cost of betrayal is higher; hence, this candidate has a lower incentive to win. In addition, a less policy-motivated candidate wins against a more policy-motivated candidate since the candidate with higher policy motivation will betray his...