![]()

CHAPTER VIII

The Follow-Up Inquiry—II

Statistical Analysis and the Concept of General Adjustment

BY JOSEPH SANDLER

I

THE patients of the Industrial Neurosis Unit of Belmont Hospital are distinguished from most other neurotic groups by the fact that they have been selected as patients on the basis of specific disturbances of working capacity, over and above any other manifestations of neurotic illness or character disorder. It is the therapeutic aim of the Unit to modify the patient's behaviour so that he will be better fitted to cope with the problems that beset him in real life; and in particular the Unit aims at improving his capacity in the sphere of work. The techniques used in this connection have been described elsewhere in this volume and need not be elaborated here. But any evaluation of these techniques and of the effect of the Unit as a whole on each individual patient, can only be undertaken in the light of factual knowledge of what happens to the patient after his discharge from hospital. How well in fact, do the Unit's patients adjust to their environment after leaving hospital? And what distinguishes those patients who do well from those who make a poor adjustment?

An attempt has been made to answer these two important questions by the follow-up carried out on the Unit's patients and described in the previous chapter. In addition an experimental followup study has been made on a comparative group which has not passed through the Industrial Unit, in order to obtain data which might throw some light on the functioning of the Unit. This second follow-up group and the techniques used in its study have been described, and as a discussion of this group is not relevant to the present material its further consideration will be left until later.

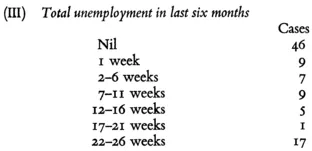

The visit paid by the Psychiatric Social Worker to those industrial cases which were followed up, elicited a mass of information which included data bearing on the patient's adjustment in different spheres. The term 'adjustment' is used here to indicate the degree to which the patient has successfully coped with the demands of reality; successfully that is, by the conventional standards of Western society. Adjustment may be measured in a number of different behavioural areas, and in a number of ways in each area. Thus adjustment in the work situation might be measured by such things as the wage being earned at the time of the P.S.W.'s visit, or by the number of days the patient has worked in the period following his discharge. Which of these, we may ask, should be taken as the index of adjustment in the work field? The first is in a way a measure of the patient's work adjustment at the time of the visit, while the second takes into account one aspect of his behaviour during the whole six months following discharge from hospital. Both are measures of adjustment in relation to work, and yet neither comes near to describing the complete adaptation made by the patient in this sphere.

Ideally, all the possible different adjustment measures should be used, but this is prevented by the practical difficulty of having to answer the question 'How well has the patient done?', by reference to a multitude of measures. The tracing of the relationship between the data collected in relation to the different patients while they were in hospital, to all these adjustment measures, would be a task which, if not impossible, would be sufficient to dishearten the most enthusiastic statistician.

There is, however, a possible way of overcoming the difficulties inherent in the use of a large number of indices of adjustment. This is by attempting to reduce the number of measures so that what is common to a representative set of adjustment measures is taken as the essence of adjustment. Those measures of adjustment which seem to cover the different aspects of the field under investigation can be reduced in such a way to their common denominators, and these common denominators may be used as the yardstick against which we assess the recovery of our patients.

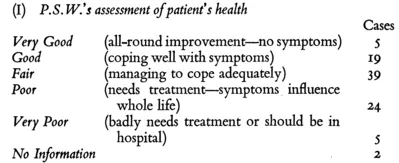

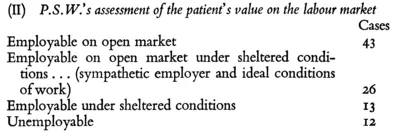

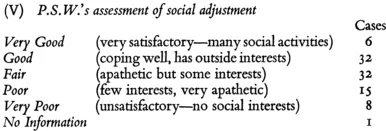

The practical method of seeking these common elements is some form of factor analysis, and such a method was applied to eleven measures of adjustment derived from the data collected by the P.S.W. in her follow-up interview. These eleven criteria were chosen from the point of view of the expressed therapeutic aims of the Unit, and converted into quantitative scales.

Explanations of the basis of assessment are given below.1

(VI) Average length of job in past six months

Totally unemployed patients were given a score of o.

(VII) Patient's assessment of improvement since leaving hospital

Better, worse, or the same since discharge.

(VIII) Social adjustment at work

Very good (gets on well with everyone).

Good (gets on well with most).

Fair (gets on not too badly with others, but keeps mostly to himself).

Poor (suspicious of most—is not liked).

Very poor (hates all others at work).

(IX) Average wage in last six months: The totally unemployed group

were given a wage of o. (Average wage while working only.)

(X) P.S. W.'s estimate of standard of environmental conditions

No account was taken of suitability.

Very good—good dwelling and furniture—comfortable.

Good—reasonable conditions.

Fair—conditions not too good—badly furnished.

Poor—very poorly furnished—very limited accommodation.

Very poor—unfit to live in—Rowton House.

(XI) Proportion of working time at work

The negative of absenteeism. Patient's own estimate. Unemployed group received o for this item.

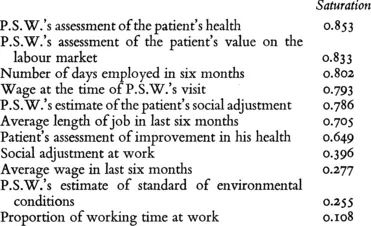

At the time that the statistical analysis was started, results were available for eighty-two patients. Using these results, the matrix of product-moment intercorrelations between these measures was computed, and factored by Thurstone's Centroid Method.1 This yielded a most gratifying result. The correlations could almost completely be accounted for by one common general factor which contributed 41.3 per cent of the variance of the original measures. The saturation of each measure with this common quality is given below.1

The factor saturations are in effect the correlations of the adjustment measures with the single common factor, and it will be seen that five are above 0.75. It is certain that three of the four lowest saturated measures— viz. social adjustment at work, average wage in last six months, and proportion of working time at work (the negative of absenteeism) suffered an increased unreliability owing to a number of distortion effects. The common factor accounts for 66.3 per cent of the variance of the five highest measures.

The results of the factor analysis indicate that it is legitimate to speak of the patient's general adjustment after his discharge from the Unit, for this single factor common to all the measures is manifestly a general tendency to make a good or bad 'adjustment'. It is a synthesis of eleven different measures of adjustment, and is their common core.

At this point it might be well to mention the possibility of so-called 'halo-effect'—i.e. the tendency for the ratings and assessments to be influenced by the rater's general impression of the individual rated. Almost certainly the assessments are not completely free from its influence, and indeed it must enter into all subjective ratings. If it does enter to any considerable extent, it must be regarded as a limitation to the accuracy of the original measurements, but it does not invalidate the use of the general adjustment factor as the best measure of the common elements in the description of the patient as he appeared at the follow-up interview. Against the possibility of strong influence of halo effect we must weigh the fact that the P.S.W. was on her guard against it, and the fact that the relatively objective measures such as number of days employed in six months an...