eBook - ePub

Ancient Egyptians (2 Vols)

J. Gardner Wilkinson

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 256 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Ancient Egyptians (2 Vols)

J. Gardner Wilkinson

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Written in 1836, this two-volume study has enduring importance in the field of Egyptology. Covering topics including Egyptian homes, ceremonies, hunting, religious rites, and castes, it provides a comprehensive account of ancient Egyptian life and practices. The work is illustrated with numerous anecdotes and hundreds of beautiful woodcuts.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Ancient Egyptians (2 Vols) als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Ancient Egyptians (2 Vols) von J. Gardner Wilkinson im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus History & Egyptian Ancient History. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS

OF

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS

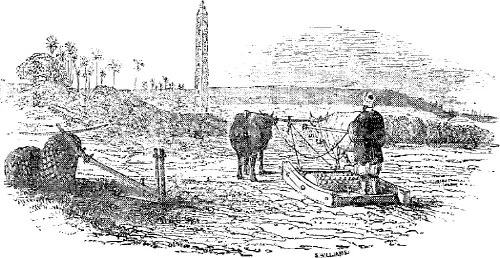

H. Khonfud, or clod-crushing machine used after the land is ploughed. Heliopolis—Cairo in the distance.

CHAPTER VI

THE DIFFERENT CLASSES OF EGYPTIANS — THE THIRD CLASS — THE HUSBANDMEN — AGRICULTURE — PRODUCTIONS OF EGYPT — HARVEST — FESTIVALS OF THE PEASANTS — GARDENERS, HUNTSMEN, BOATMEN OF THE NILE.

THE high estimation in which the priestly and military professions were held in Egypt placed them far above the rest of the community; but the other classes had also their degrees of consequence, and individuals enjoyed a position and importance in proportion to their respectability, their talents, or their wealth.

According to Herodotus, the whole Egyptian community was divided into seven tribes, one of which was the sacerdotal, another of the soldiers, and the remaining five of the herdsmen, swineherds, shopkeepers, interpreters, and boatmen. Diodorus states that, like the Athenians, they were distributed into three classes—the priests; the peasants or husbandmen, from whom the soldiers were levied; and the artizans, who were employed in handicraft and other similar occupations, and in common offices among the people—but in another place he extends the number to five, and reckons the pastors, husbandmen, and artificers, independent of the soldiers and priests. Strabo limits them to three, the military, husbandmen, and priests; and Plato divides them into six bodies, the priests, artificers, shepherds, huntsmen, husbandmen, and soldiers; each peculiar art or occupation, he observes, being confined to a certain subdivision of the caste, and every one being engaged in his own branch without interfering with tike occupation of another. Hence it appears that the first class consisted of the priests; the second of the soldiers; the third of the husbandmen, gardeners, huntsmen, boatmen of the Nile, and others; the fourth of artificers, tradesmen and shopkeepers, carpenters, boatbuilders, masons, and probably potters, public weighers, and notaries; and in the fifth may be reckoned pastors, poulterers, fowlers, fishermen, labourers, and, generally speaking, the common people. Many of these were again subdivided, as the artificers and tradesmen, according to their peculiar trade or occupation; and as the pastors, into oxherds, shepherds, goatherds, and swineherds; which last were, according to Herodotus, the lowest grade, not only of the class, but of the whole community, since no one would either marry their daughters or establish any family connexion with them. So degrading was the occupation of tending swine, that they were looked upon as impure, and were even forbidden to enter a temple without previously undergoing a purification; and the prejudices of the Indians against this class of persons almost justify our belief in the statement of the historian.

Without stopping to inquire into the relative rank of the different subdivisions of the third class, the importance of agriculture in a country like Egypt, where the richness and productiveness of the soil have always been proverbial, suffices to claim the first place for the husbandmen.

The abundant supply of grain and other produce gave to Egypt advantages which no other country possessed. Not only was her dense population supplied with a profusion of the necessaries of life, but the sale of the surplus conferred considerable benefits on the peasant, in addition to the profits which thence accrued to the state; for Egypt was a granary where, from the earliest times, all people felt sure of finding a plenteous store of corn;1 and some idea may be formed of the immense quantity produced there, from the circumstance of “seven plenteous years” affording, from the superabundance of the crops, a sufficiency of corn to supply the whole population during seven years of dearth, as well as “all countries” which sent to Egypt “to buy” it, when Pharaoh by the advice of Joseph2 laid up the annual surplus for that purpose.

The right of exportation, and the sale of superfluous produce to foreigners, belonged exclusively to the government, as is distinctly shown by the sale of corn to the Israelites from the royal stores, and the collection having been made by Pharaoh only; and it is probable that even the rich landowners were in the habit of selling to government whatever quantity remained on hand at the approach of each successive harvest; while the agricultural labourers, from their frugal mode of living, required very little wheat and barley, and were generally contented, as at the present day, with bread made of the Doora3 flour; children and even grown persons, according to Diodorus, often living on roots and esculent herbs, as the papyrus, lotus, and others, either raw, toasted, or boiled.

The Government did not interfere directly with the peasants respecting the nature of the produce they intended to cultivate; and the vexations of later times were unknown under the Pharaohs. They were thought to have the best opportunities of obtaining, from actual observation, an accurate knowledge on all subjects connected with husbandry; and, as Diodorus observes, “being from their infancy brought up to agricultural pursuits, they far excelled the husbandmen of other countries, and had become acquainted with the capabilities of the land, the mode of irrigation, the exact season for sowing and reaping, as well as all the most useful secrets connected with the harvest, which they had derived from their ancestors, and had improved by their own experience.” “They rented,” says the same historian, “the arable lands belonging to the kings, the priests, and the military class, for a small sum, and employed their whole time in the tillage of their farms;” and the labourers who cultivated land for the rich peasant, or other landed proprietors, were superintended by the steward or owner of the estate, who had authority over them, and the power of condemning delinquents to the bastinado. This is shown by the paintings of the tombs; which frequently represent a person of consequence inspecting the tillage of the field, either seated in a chariot, walking, or leaning on his staff, accompanied by a favourite dog.4

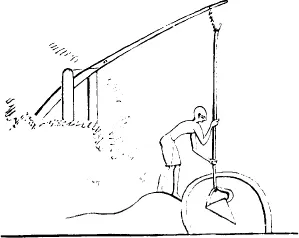

356.Shadóof for watering the lands.Thebes.

Their mode of irrigation was the same in the field of the peasant as in the garden of the villa;5 and the principal difference in the mode of tilling the former consisted in the use of the plough.

The usual contrivance for raising water from the Nile for watering the crops was the shadóof, or pole and bucket, so common still in Egypt; and even the water-wheel appears to have been employed in more recent times.

The sculptures of the tombs frequently represent canals conveying the water of the inundation into the fields; and the proprietor of the estate is seen, as described by Virgil, plying in a light painted skiff or papyrus punt, and superintending the maintenance of the dykes, or other important matters connected with the land. Boats carry the grain to the granary, or remove the flocks from the lowlands; as the water subsides, the husbandman ploughs the soft earth with a pair of oxen; and the same subjects introduce the offering of first-fruits to the gods, in acknowledgment of the benefits conferred by “a favourable Nile.” The main canal was usually carried to the upper or southern side of the land, and small branches, leading from it at intervals, traversed the fields in straight or curving lines, according to the nature or elevation of the soil.

The inundation began about the end of May, sometimes rather later: but about the middle of June the gradual rise of the river was generally perceived; and the comparatively clear stream assumed a red and turbid appearance, caused by the floods of the rainy season in Abyssinia: the annual cause of the inundation. It next assumed a green appearance, and being unwholesome during that short period, care was taken to lay up in jars a sufficient supply of the previous turbid but wholesome water, which was used until it reassumed its red colour. This explains the remark of Aristides, “that the Egyptians are the only people who preserve water in jars, and calculate its age as others do that of wine;” and may also be the reason of water-jars being an emblem of the inundation; though the calculation of the “age” of the water is an exaggeration. Perhaps, too, the god Nilus being represented of a blue and a red colour may allude to the two different appearances of the low and high Nile.

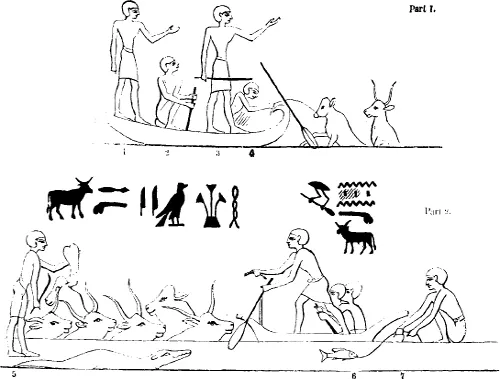

357.Cattle resened from the inundation.Beni Hassan.

Part 1. Figs. 1 and 3. Men calling to others to drive the cattle towards the boat 2. Rower 4. Pulling a cow by noose to the boat.

Part 2. Fig. 5. Driving the cattle towards the boat. 6. Throwing a noose, in order to drag them after the boat (the end of it is effaced). 7. The rowers. 8. A man on the bank fishing. (See the Vignette at the head of chap. VIII.)

In the beginning of August, the canals were opened, and the waters overflowed the plain. That part nearest the desert, being the lowest level, was first inundated; as the bank itself, being the highest, was the last part submerged, except in the Delta, where the levels were more uniform, and where, during the high inundations, the whole land, with the exception of its isolated villages, was under water. As the Nile rose, the peasants were careful to remove the flocks and herds from the lowlands; and when a sudden irruption of the water, owing to the bursting of a dyke, or an unexpected and unusual increase of the river, overflowed the fields and pastures, they were seen hurrying to the spot, on foot, or in boats, to rescue the animals, and to remove them to the high grounds above the reach of the inundation. Some, tying their clothes upon their heads, dragged the sheep and goats from the water, and put them into boats; others swam the oxen to the nearest high ground; and if any corn or other produce could be cut or torn up by the roots, in time to save it from the floo...