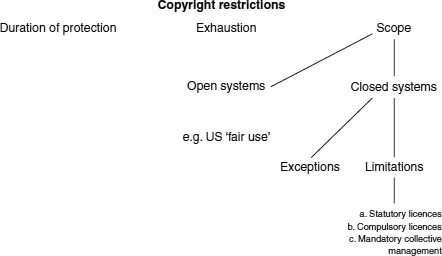

The legal nature of the private copying limitation is not explicitly determined and, as the Commission acknowledges, Member States have adopted diverse approaches on this issue.6 This creates legal uncertainly both to end users and to rightholders and, while some consumer groups claim a user ‘right’ to private copy,7 the copyright industry files lawsuits against individual users for exercising this ‘right’.8 To determine the legal nature of the private copying limitation of Article 5(2)(b) EUCD, it is essential to examine the framework in which private copying is set, namely the framework of restrictions to copyright protection, as graphically presented in Figure 1.1.

1.1.1 Copyright restrictions

There are three main types of restrictions of the exclusive rights in copyright. The first includes restrictions as to the term of protection. In the European Union, this type of time restriction is incorporated in the Duration Directive.9 A second restriction is the ‘exhaustion’ doctrine,10 known in the United States as the ‘first-sale’ doctrine.11 When works have been published on behalf of the rightholders, or with their consent, for instance by way of distribution to the public,12 the owners’ right to control any further distribution, sale, hiring or loan of those exact same copies is ‘exhausted’.13 The third type of copyright restrictions refers to scope. These restrictions are justified for reasons of social, cultural and educational policy and purport to protect the public interest, namely the welfare of the public.14

1.1.1.1 Open and closed systems of scope restrictions

As regards scope restrictions, there might be an open system, such as the US ‘fair-use’ doctrine,15 or a closed regime of exceptions, such as those listed under the Copyright Directive.16 Where exclusive rights are drafted in specific terms, exceptions and limitations to these rights are broadly construed. For instance, the narrow definition of economic rights in the United States comes with an open defence on fair use. This defence leaves sufficient room for the Courts to interpret unauthorised uses as infringing or not, based on a four-factor test.17 By contrast, European copyright law defines exclusive rights broadly and then sets exceptions that are strictly defined and narrow in scope.18 For example, while the reproduction right of Article 2 of the Copyright Directive encompasses a wide range of exploitation acts, the exceptions and limitations applicable to this right apply to a series of specifically enumerated instances. In this light, whereas the exclusive rights are construed as widely as possible, limitations are subject to restrictive interpretation and cannot be applied by way of analogy.19

1.1.1.2 Exceptions v. limitations

The ‘exceptions and limitations’, to which the structure and official caption of Article 5 of the Copyright Directive refer, form part of a closed system of scope restrictions to copyright. Spoor points out that while the terms ‘exception’20 and ‘limitation’ are often used interchangeably by established national law, international Conventions and EC Directives, they are not identical.21 Many terms might be used to define copyright’s inherent limits, such as the terms ‘limitations’, ‘exceptions’, ‘exemptions’22 and ‘restrictions’, and all will raise different connotations to the mind of the user.23 Guibault argues that while the term ‘exception’ is widely accepted and used in many international instruments,24 the term ‘limitation’ has the merit of being more neutral: it can be understood as permitting certain activities that would otherwise infringe copyright.25

What is more, the term ‘limitation’ reflects more appropriately the concept of the ‘limits’ that determine the legal nature of legally guaranteed freedoms. These ‘limits’ are tools in determining the scope of exclusive rights and not ‘exceptions’ to a rule.26 For instance, private copying is a limitation to the reproduction right in terms that it helps better defining the scope of this right. In the absence of this limitation, the entitlement over acts of reproduction would be absolute, covering also copying carried out for private non-commercial purposes. As I will illustrate in the following chapter, the definition of the reproduction right in Article 2 of the Copyright Directive is overly broad, covering a wide range of activities. What is doctrinally interesting in this definition, however, is that – unlike other exclusive rights – the concept of the ‘public’ is missing. The distribution right, for instance, takes effect when addressed to the public and the same occurs to all other rights in copyright. The concept of the ‘public’ does not feature in the statutory definition of the reproduction right and only an indirect reference to it may be inferred, in the sense that copies should be perceptible by the public. The broad construal of the reproduction right is balanced by the private copying limitation. The latter is meant to better define the scope and the very nature of the reproduction right by excluding certain activities from the scope of copyright entitlement which is, hence, not absolute.27

This has an important practical consequence: rightholders have no power to authorise or prohibit private non-commercial copying of their works, plainly because this activity is statutorily exempt from their sphere of control. Private copying remains outside copyright entitlement. Rightholders can only challenge the permissible limits of the private copying limitation by invoking, for instance, that use was not made in a private context or that it was carried out for commercial purposes.28 As I will discuss later on, in the digital world the conceptual contours of the private copying limitation, i.e. its private and non-commercial nature, are not clearly demarcated. It is only when these boundaries of permissibility become less sharp that a legal action may flourish.

By virtue of Article 5(2)(b), private copying is permitted ‘on condition that the rightholders receive fair compensation’. This may either give rise to statutory licensing, compulsory licensing or mandatory collective management.

1.1.1.3 Statutory licences, compulsory licences or mandatory collective management?

Copyright limitations can be further distinguished into three categories. The first includes statutory licences.29 Under a statutory licence, copyright works can be used without authorial consent but against payment of remuneration.30 Statutory licences are a compromise between the interests of rightholders and users for reasons of public policy which are not so paramount to occur on a remuneration-free basis,31 or for the alleviation of market-failure symptoms.32 For instance, the invention of video and tape recorders in the 1970s was considered to affect the legitimate interests of the rightholders; as a result, certain exclusive rights were replaced by a right to equitable remuneration.33 Statutory licences maintain the right to authorise and prohibit certain activities reserved by copyright and it is only the exercise of this right that is regulated.

A second category of copyright limitations are compulsory licences. Under this type of limitation, rightholders are obliged to grant individual licences, the conditions and the price of which are determined jointly with the user or fixed by authorities where no agreement can be reached. Compulsory licensing is a less frequent form of limitation that arose as response to the increasing complexity of legal relations vis-à-vis technological change.34 As opposed to statutory licensing, compulsory licensing creates an obligation on rightholders to contract with users. Well-known examples of compulsory licensing are those incorporated in the Berne Convention on the broadcasting of literary and artistic works and the recording of musical works.35 Compulsory licences have not been popular in Europe due to the fact that they mostly reflect the interests of the industry rather than those of the society as a whole,36 this coming in contradiction with the author’s right tradition.

The third type of copyright limitations is the mandatory collective administration of rights.37 This type of limitation requires that certain rights are exercised exclusively through a collecting societ...