![]()

Part One

Introduction to Ecopedagogy

![]()

1

Ecopedagogy

An Introduction

To stop the downward spiral of intensifying environmental violence that leads to social violence, we need to better understand what the politics of humans’ violent actions are in order to determine why the violence is taking place (i.e., the root causes). The overall question problematized throughout this book is this: How can environmental pedagogies end socio-environmental oppressions and planetary unsustainability? What pedagogies are necessary for “true” sustainability for all of human societies (i.e., the world) and all else that is Earth. The root causes of environmental violence are most often purposely hidden, to sustain and intensify the benefits of hegemony for a few. Ecopedagogies have the overall goal of unveiling these hidden politics—for teaching, reading, and research toward this end.

This chapter will discuss the overall key tenets of ecopedagogy, as well as introduce some foundational Freirean aspects of ecopedagogies, with discussion on how environmental pedagogies (dis)connect us, as humans making up the world, with the rest of Nature, making up Earth. Beyond “environmental pedagogies,” ecopedagogical work also includes critically deconstructing pedagogies on the environment, with this phrase indicating education which can either be for environmental “well-being” or cause environmental destruction. Stated a bit differently, “pedagogies on the environment” will denote any type of teaching on the environment, but this does not necessarily mean that the underlying foundation is environmentalism, either intentional or not, or consciously or not. This is different from environmental pedagogies, in which environmental well-being is the goal, regardless of whether or not the teaching is effective. Ecopedagogical work deconstructs if pedagogies on the environment models are environmental pedagogies, in which what is taught on the sustainability between the world and Earth is truly toward this goal. Ecopedagogical work deconstructs the politics of the former and the latter, to see who truly benefits and who is negatively affected within the ideologies of the hidden curricula (e.g., what is indirectly being taught through curricula), as defined by Henry Giroux (2001) and others. The discussions of these topics will begin here and will continue throughout this book, including the next chapter on teaching literacy to read the world as part of Earth (i.e., ecopedagogical literacies) and Chapter 3, which will focus on the reinvention of Freirean scholarship for ecopedagogical teaching and scholarship to emerge.

As ecopedagogy is reinvented from Freire, it is important to remember that Paulo Freire was a teacher of literacy—teaching to read the word in order to read and reread the world. Reading is not passive, to only gain understanding, but to critically determine action. As Freire’s (1997) quote indicates, reading is for transformational praxis through better understanding the world, rather than to know the world as non-transformable (or static and fatalistic with a predetermined future).

One of the fundamental differences between me and such fatalistic intellectuals—sociologists, economists, philosophers, or educators, it does not matter—lies in my never accepting, yesterday or today, that educational practice should be restricted to a “reading of the word,” a “reading of text,” but rather believing that it should also include a “reading of context,” a “reading of the world.”

Critical/Freirean pedagogies are not only to understand socio-environmental issues but for praxis. Praxis is a complex and multifaceted goal as Moacir Gadotti (1996), among others, has argued, which will be further discussed throughout this book, but here, in the field of ecopedagogy, it is how to teach for learners’/readers’ transformative actions through deepened and widened reflections toward ending socio-environmental injustices, violence, and dominance over Nature.

As I write “Earth” without the article “the,” as in “the Earth,” it is not in error but rather so as to not objectify Earth as an object, as within tenets of ecolinguistics (Stibbe, 2014, 2012; Derni, 2008; Fill, 2001). The “world” signifies all humans and their groupings, which will be discussed further in this chapter, but a key aspect of ecopedagogy and its literacy is deconstructing social and environmental violence in the world within Earth. Teaching to understand, or crucially read, the connections between social violence/injustice and environmental violence, which are inherently inseparable, is the goal of ecopedagogies (Gadotti, 2008b, 2008c). These connections are often structurally hidden to conceal who really benefits and the many more negatively affected. This is with the assumption, which I have introduced elsewhere, that all environmental violence happens to benefit somebody, with ecopedagogical teaching to read what the politics of the degrees of who benefits and who suffers from environmental violence are (Misiaszek, 2018b). This assumption is also from the work of Michael Apple.1 Ecopedagogues teach to read the politics of these connections, and ecopedagogical research seeks the “hows” and “whys” of these connections not being taught or being mistaught in education (formal, nonformal, and informal education; environmental pedagogies and pedagogies on the environment) (Misiaszek, 2018b, 2011). A topic that will be discussed more in length later is that ecopedagogical research is inherently being done in ecopedagogical learning and reading spaces. Throughout this book I will utilize the term “ecopedagogical work” to indicate ecopedagogical teaching, literacy/reading, and research—only naming the specific type when directly referenced among the three.

Ecopedagogical work attempts to deconstruct the continuum of environmental violence to devise transformative actions that can be undertaken by students to end environmental violence and achieve sustainability at all levels from local-to-planetary. What I mean by a continuum of environmental violence is that we, as the world, utili ze the rest of Earth for our own needs and wants. If there was no benefit for anyone, humans would not cause environmental violence. For example, why would we drill deep into the oceans’ floors for a slippery, viscous fluid (i.e., oil) unless it served some sort of purpose? Oil serves many purposes such as for lubrication and as the fuel we use every day. Of course, there are many, many factors of oil such as unequal usage, distribution, and almost endless pollution effect, but I will get to those later in the book. This example illustrates a key factor of ecopedagogical work for better reading to unveil the politics of oil mining and consumption that lead to environmental violence and, in turn, lead to social violence. There are almost limitless questions to problematize within this example. One is questioning what is “needed” compared to what is “wanted,” especially within social justice models. Another is what the other possible sources of energy are and the politics behind oil remaining a primary source, with the accompanying question of who benefits from this (e.g., deconstructing the politics of oil production).

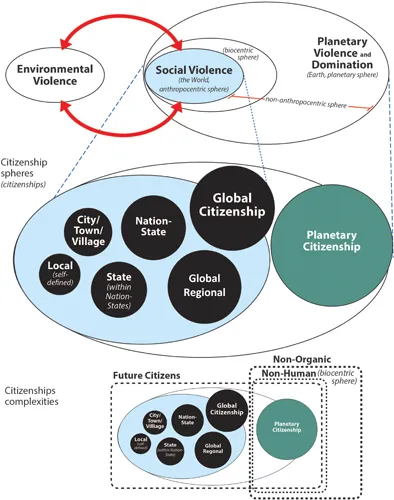

There are also questions about the effects of our environmental violence beyond humans. Ecopedagogical work also examines things that are beyond the world (i.e., beyond humans, beyond the anthropocentric sphere)—all else that make up Earth. In this book, the non-anthropocentric sphere will indicate all else that is Earth beyond humans. Other terminologies that will be utilized are within the concepts of “spheres,” with Earth as the planetary sphere that includes all humans of the anthropocentric sphere (i.e., the world) and the “non-anthropocentric sphere” as the planetary sphere not including humans (i.e., the anthropocentric sphere). Ecopedagogical content and goals are infinitely complex within and between these spheres, among which this book will address some, but all-inclusiveness is impossible. To help guide some of the key aspects of ecopedagogical work, Figure 1.1 illustrates the vast scope and the overall goals of such work.

Figure 1.1 World-Earth spheres.

The three interrelated graphics in Figure 1.1 have evolved through my ecopedagogical work, with other versions of it given in previous publications (2018b, 2011). Ecopedagogical work focuses on the connections between environmental violence and social violence, as well as how environmental violence affects everything else that makes up the planetary sphere, as illustrated in the figure. The imagery of the connections between environmental and social violence have figured throughout my work; however, the graphic illustrates the world within Earth with some key aspects of the complexities of the ways in which effects of development and sustainability must be widened to the planetary sphere (i.e., Earth holistically). The planetary sphere is illustrated as divided between all that is living with the label “biological sphere” that includes the world (anthropocentric sphere) and the rest of Earth. Throughout this book, the sphere of Earth outside of the world will be called the “non-anthropocentric sphere.” However, these divisions as “hard” boundaries are false, as between the world (anthropocentric sphere), the biological sphere, the non-anthropocentric sphere, and the rest of Earth. These spheres are intertwined together with limitless complexities between us, as humans, within the larger biological sphere, and within the complexities of the planetary sphere. Figure 1.1 will be referenced throughout this book, especially in the discussions on citizenships, which are denoted by the bottom two illustrations in the figure.

The graphic illustrates also the complexities of “who” is included within the question of “who” benefits and “who” suffers—for example, pondering if the inclusion of “who” is within the world or rather also beyond the world to include Earth holistically.2 Where in graphic is/are the “who” represented, as an entity(ies) that is oppressed/dominated by environmental violence, are educational models concerned with? As stated previously, critical pedagogies have the goal of understanding oppressions better, with specific foci on who suffers the “most,” but ecopedagogies expand this determination beyond humans to the planetary sphere. However, as described in the next section, the essence of ecopedagogical work is to understand oppressions from those who suffer the “most” and are dominated within the non-anthropocentric sphere.

Ecopedagogical work coincides with critical pedagogical work (even more so specifically with Freirean pedagogies, which will be discussed throughout this book), with the focus on teaching about human actions that are acts of environmental violence. Environmental violence emerging from the world, as human actions, is an essential defining factor of ecopedagogical work in that “naturally” occurring factors, such as hurricanes, forest fires from lightning, and earthquakes are not focused upon. However, the reason for emphasizing “naturally” in the previous sentence is because those environmental disasters can be caused by humans (e.g., storms intensifying as a consequence of global warming), and/or the disastrous effects might be mostly within the anthropocentric sphere (e.g., human-made structures affected by fires and earthquakes), making ecopedagogical work much more complicated. So ecopedagogical work problematizes why we, as humans, commit acts of environmental violence.

This book will largely focus on environmental violence done in the name of “development” and “citizenship”—both being reasons for promoting and/or lessening environmental violence toward planetary sustainability. It is human actions that directly or indirectly lead to environmental violence as we, as self-reflective, historical beings, can dream of utopias (three characteristics that Freire (2000) expressed as unique to humans). The (in)direct aspects are complex and make the “hiding” of the true reasons for social-environmental violence unfortunately easier. This is one of many ways, among others that will be discussed throughout this book, in which “hiding” socio-environmental connections results in less protest against environmental violence, calling for urgent ecopedagogical work.

“Development” and “citizenship” are often seen as primary reasons for public education to emerge; however, most critical pedagogues argue that the ultimate aim of schooling historically has often been social control and sustaining power stratifications (e specially hegemony) rather than all-inclusive well-being, democratic participation, and empowerment. Problematizing constructs of development is essential within ecopedagogical work to question whose development it is and what its effects, ranging from the local to the planetary, are. As will be discussed later, the importance of development can be witnessed as the “D” within the environmental pedagogy ESD, but what ecopedagogical work focuses on is problematizing what the “D” is, especially in relation to the “S” (i.e., Sustainability). Is development being taught as local-to-global all-inclusive progress, or is it progress for a few and, if yes, why? Beyond this question is how such a “development,” or de-development, coincides with planetary sustainability or unsustainability. Questions of (un)sustainability are ones that must be problematized within the planetary sphere toward Earth’s holistic balance. Returning to the notion that environmental violence is a continuum resulting in both benefits and oppressions to the world, ecopedagogical work on planetary sustainability problematizes what the balance of environmental violence from local-to-planetary levels is (Misiaszek, 2018b). As will be discussed in the book, ecopedagogical work deconstructs how different populations are socio-environmentally affected differently, often coinciding with sociohistorical oppression divisions (e.g., gender, race, e...