![]()

PART 1

Creative Thinking

I begin to wonder how many things I know would suddenly take on new meanings if only I could perceive the connections.

— ROBERT SCOTT-BERNSTEIN

We are educated to be analytical, logical thinkers. Consequently, we have the ability to make common associations between subjects that are related or at least remotely related. We are far better at associating two things (for example, apples and bananas are both fruits) than we are at forcing ourselves to see connections between things that seem to have no association (for example, a can opener and a pea pod).

Jeff Hawkins, in his book On Intelligence, explains how our ability to associate related concepts limits our ability to be creative. We form mental walls between associations of related concepts and concepts that are not related. For example, if asked to improve the can opener, we will make connections between all our common experiences and associations with can openers. Our fixation with our common associations will produce ideas for can openers that are very similar to the can openers that exist.

Developing the skill of forcing connections between unrelated things will tear down the walls between related and unrelated concepts. What connections, for example, can you force yourself to see between a can opener and a pea pod?

The function of a can opener is “opening.” How do things in other domains open? For example, in nature a pea pod opens when a seam weakens as the pod ripens. Thinking simultaneously about a pea pod and a can opener in the same mental space will force a mental connection between the pea pod seam and a can opener. This inspires the idea of opening a can by pulling a weak seam (like the one in a pea pod). Instead of an idea to improve the can opener, we’ve produced an idea for a new can design. This idea is one you would never get using conventional thinking.

This is an example of conceptual blending, which is the act of combining, or relating, unrelated items in order to solve problems, create new ideas, and even rework old ideas. It succeeds because it is not possible to think of two subjects, no matter how remote, without making connections between the two. It is no coincidence that the most creative and innovative people throughout history have been experts at forcing new mental connections via the conceptual blending of unrelated subjects.

Part 1 of this book explores the nature of conceptual blending and gives practical examples of how to use this technique in a variety of different ways to inspire new ideas and solutions to problems.

![]()

Every child is an artist.

The problem is how to remain an artist

once we grow up.

— PABLO PICASSO

We were all born spontaneous and creative. Every one of us. As children we accepted all things equally. We embraced all kinds of outlandish possibilities for all kinds of things. When we were children, we knew a box was much more than a container. A box could be a fort, a car, a tank, a cave, a house, something to draw on, and even a space helmet. Our imaginations were not structured according to some existing concept or category. We did not strive to eliminate possibilities; we strove to expand them. We were all amazingly creative and always filled with the joy of exploring different ways of thinking.

And then something happened to us: we went to school. We were not taught how to think; we were taught to reproduce what past thinkers thought. When confronted with a problem, we were taught to analytically select the most promising approach based on history, excluding all other approaches, and then to work logically in a carefully defined direction toward a solution. Instead of being taught to look for possibilities, we were taught to look for ways to exclude them. It’s as if we entered school as a question mark and graduated as a period.

Consider a child building something with a Lego construction set. She can build all kinds of structures, but there are clear, inherent constraints on the design of objects that can be made with the set. They cannot be put together any which way: they will not stay together if unbalanced and gravity pulls them apart. The child quickly learns the ways that Legos go together and the ways they don’t go together. She ends up building a wide variety of structures that satisfy the toy’s design constraints.

If the only constraint were to “make something out of plastic,” and the child had at her disposal every method of melting and molding plastic, the currently possible Lego constructions would be only a tiny fraction of the possible products and would make the Lego constructions look contrived, not the result of motivation, when compared to her other products.

With Legos it is the constraints inherent in the design that limit what can be built. With us, it is the thinking patterns that formal education has firmly wired in our brains that limit our imagination and inventiveness.

Our mental patterns enable us to simplify the assimilation of complex data. These patterns let us rapidly and accurately perform routine tasks such as driving an automobile or doing our jobs. Habitual pattern recognition provides us with instant interpretations and permits us to react quickly to our environment. When someone asks you, “What is six times six?” the sum “thirty-six” automatically appears in your mind. If a man is born in 1952 and dies in 1972, we know immediately that the man was twenty.

Though pattern recognition simplifies the complexities of life, it also makes it hard for us to come up with new ideas and creative solutions to problems, especially when confronted with unusual data. This is why we so often fail when confronted with a new problem that is similar to past experiences only superficially, and that is different from previously encountered problems in its deep structure. Interpreting such a problem through the prism of past experience will, by definition, lead the thinker astray. For example, the man in the above example died at age forty-nine, not twenty. In this case, 1952 is the number of the hospital room where he was born, and 1972 is that of the room where he died.

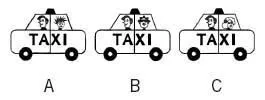

In the following thought experiment, which taxi is out of order? See if you can solve it before you continue reading.

One of the hallmarks of a creative thinker is the ability to tolerate ambiguity, dissonance, inconsistency, and things out of place. Creative thinkers will look at problems many different ways and will examine all the variables involved, searching for the unexpected. For example, in the taxi problem, the letters A, B, and C are also considered part of the whole and not as separate labels. To solve the problem, move taxi C to the front of the line of letters to spell cab.

Our minds are marvelous pattern-recognition machines. We look at the illustration below, and our brains immediately recognize a pattern: we see the word optical. When we see something, we immediately decide what it is and move on without much thought.

Success at discerning patterns of one sort naturally lessens one’s propensity to recognize patterns of another. Notice that once we recognize the word optical, we fail to recognize the word illusion. The more accustomed we are to reading a word as a stand-alone word with one meaning, the more difficult it is for us to recognize anything new or different about it. Namely, it is either optical or not optical. We do not pay attention to the background shapes. This is a standard aspect of reading. As a result, experts in “the standard of anything” may be those least qualified when it comes to developing or creating anything new.

WE ARE TAUGHT TO PROCESS INFORMATION

THE SAME WAY OVER AND OVER

THOUGHT EXPERIMENT

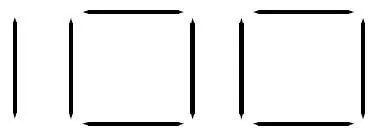

Martin Gardner had a phenomenal career creating several classic puzzles, which were published in Scientific American and more than seventy books. Following is one of them, a puzzle made with toothpicks.

Can you change “100” to “CAT” by moving just two of these toothpicks?

(Answer at end of chapter.)

This is difficult for many of us, because we are taught to process information the same way over and over again instead of searching for alternative ways. Once we think we know what works or can be done, it becomes hard for us to consider alternative ideas. We’re taught to exclude ideas and thoughts that are different from those we have learned.

When confronted with a truly original idea, we experience a kind of conceptual inertia comparable to the physical law of inertia, which states that objects resist change; an object at rest remains so, and an object in motion continues in the same direction unless stopped by some force. Just as physical objects resist change, ideas at rest resist change; and ideas in motion continue in the same direction until stopped. Consequently, when people develop new ideas, these new ideas tend to resemble old ones; new ideas do not move much beyond what exists.

When Univac invented the computer, the company refused to talk to businesspeople who inquired about it, because, they said, the computer was invented for scientists and had absolutely no business applications. Then along came IBM, who captured the market. Next the experts at IBM, including its CEO, said that they believed, based on their expertise in the computer market, there was virtually no market for the personal computer. In fact, their market research indicated that no more than five or six people in the entire world had need of a personal computer.

Interestingly, one of the rules taught to students seeking a master’s degree in business administration is that surprise should be minimized in the workplace. Much of what is taught to MBA candidates is aimed at reducing ambiguity and dissonance to promote predictability and order in the corporation. Yet if these rules had always applied to businesses, we would not have disposable razors, fast-food restaurants, copier machines, personal computers, affordable automobiles, FedEx, microwaves, Wal-Mart, or even an Internet.

Even when we actively seek information to test our ideas to see if we are right, we usually ignore paths that might lead us to discover alternatives. This is because educators discouraged us from looking for alternatives to the prevailing wisdom. Following is an interesting experiment, originally conducted by the British psychologist Peter Wason, that demonstrates our tendency not to seek alternatives. Wason would present subjects with the following triad of three numbers in sequence.

2 4 6

He would then ask subjects to write other examples of triads that follow the number rule and explain the number rule for the sequence. T...