- 172 Seiten

- German

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation

Über dieses Buch

Bericht über die Sitzung der AG Neolithikum am 16. und 17. April 2012 im Rahmen der 20. Jahrestagung des Mittel- und Ostdeutschen Verbandes für Altertumsforschung e.V. in Brandenburg an der Havel.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Ja, du kannst dein Abo jederzeit über den Tab Abo in deinen Kontoeinstellungen auf der Perlego-Website kündigen. Dein Abo bleibt bis zum Ende deines aktuellen Abrechnungszeitraums aktiv. Erfahre, wie du dein Abo kündigen kannst.

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf mobile Endgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Perlego bietet zwei Pläne an: Elementar and Erweitert

- Elementar ist ideal für Lernende und Interessierte, die gerne eine Vielzahl von Themen erkunden. Greife auf die Elementar-Bibliothek mit über 800.000 professionellen Titeln und Bestsellern aus den Bereichen Wirtschaft, Persönlichkeitsentwicklung und Geisteswissenschaften zu. Mit unbegrenzter Lesezeit und Standard-Vorlesefunktion.

- Erweitert: Perfekt für Fortgeschrittene Studenten und Akademiker, die uneingeschränkten Zugriff benötigen. Schalte über 1,4 Mio. Bücher in Hunderten von Fachgebieten frei. Der Erweitert-Plan enthält außerdem fortgeschrittene Funktionen wie Premium Read Aloud und Research Assistant.

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ja! Du kannst die Perlego-App sowohl auf iOS- als auch auf Android-Geräten verwenden, um jederzeit und überall zu lesen – sogar offline. Perfekt für den Weg zur Arbeit oder wenn du unterwegs bist.

Bitte beachte, dass wir keine Geräte unterstützen können, die mit iOS 13 oder Android 7 oder früheren Versionen laufen. Lerne mehr über die Nutzung der App.

Bitte beachte, dass wir keine Geräte unterstützen können, die mit iOS 13 oder Android 7 oder früheren Versionen laufen. Lerne mehr über die Nutzung der App.

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation von Thomas Link,Joanna Pyzel, Thomas Link, Joanna Pyzel im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Storia & Storia mondiale. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

A Common Thread? On Neolithic Culture Contacts

and Long Distance Communication

Heiner Schwarzberg

Introduction

Depictions of the human body, mostly made of clay, are among the most remarkable features of the material culture of the Neolithic societies between the Near East and Central Europe up to the 5th millennium BC. Based on first supraregional systematizing studies of the 1960s carried out by O. Höckmann (1968) and P. Ucko (1968) and on numerous theoretical approaches as by J. Chapman (2001), P. Biehl (2003), D. Bailey (e.g. 2005; 2012), J. Chapman and B. Gaydarska (2007), S. Nanoglou (e.g. 2008) or R. G. Lesure (2011), the discussion of Neolithic figural art received new significant stimulus by recent summarizing publications of S. Hansen (2007) on the Neolithic and Chalcolithic statues in SE-Europe and of V. Becker (2011) on the anthropomorphic figurines of the Linear Pottery Culture (henceforth: LBK)1.

Since the very beginning of prehistoric research, a special variant of anthropomorphic figurines, fragmented or complete pottery vessels of human shape or with human attributes, have been found at numerous Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in a vast area extending from Mesopotamia, along Asia Minor, the Balkans and the Carpathian Basin as far as western Central Europe (Schwarzberg 2011, 15). Unlike the calculated number of more than 30.000 solid figurines in SE Europe, there are only roughly 2000 hollow, fillable and emptiable anthropomorphic statues; these nevertheless allow essential information (Hansen 2007, 2). Ornamental and structural parallels, e. g. a zonal layout of ornaments, clear differentiation into front and back sides, depictions and shape of body parts and a face, clearly prove that they have been an integral part of the Neolithic figural. Sometimes both solid and hollow statues show the same miniature jewelry, such as younger examples with drilled holes for earrings or earplugs (Schwarzberg 2011, 38, 55, 175–181).

The depictions of human bodies as pottery vessels can be divided into three different basic types of the same sujet in different levels of abstraction and reduction2:

- figural vessels

- face vessels

- face lids

Figural vessels (Schwarzberg 2011, 23–79) are characterized by a comparatively detailed depiction of the human body and its features. A figural vessel can be described as a hollow and more or less proportioned statue, often with a rimmed vessel mouth. Quite frequently they are of unique appearance and possibilities of detailed classification are limited.

In contrast, face vessels (Schwarzberg 2011, 81–134) are significantly more stylized. Quite often they can be distinguished from “simple” household pottery just by the application of a face and related features to certain positions on the outer surface, mostly at the neck or on the shoulder. Mostly there are no depictions of other body parts (László 1972, 234; Horváth 1983, 71). Small applied rudimentary arm stumps or incised or painted (female) secondary sex characteristics occur on rare occasions.

Face lids (Schwarzberg 2011, 135–166) have been used in limited areas of SE Europe to be set on top of medium and large size vessels with cylindrical necks and wide shoulders to attain a human shape (László 1972, 211; Vinča 2008, fig. 65).

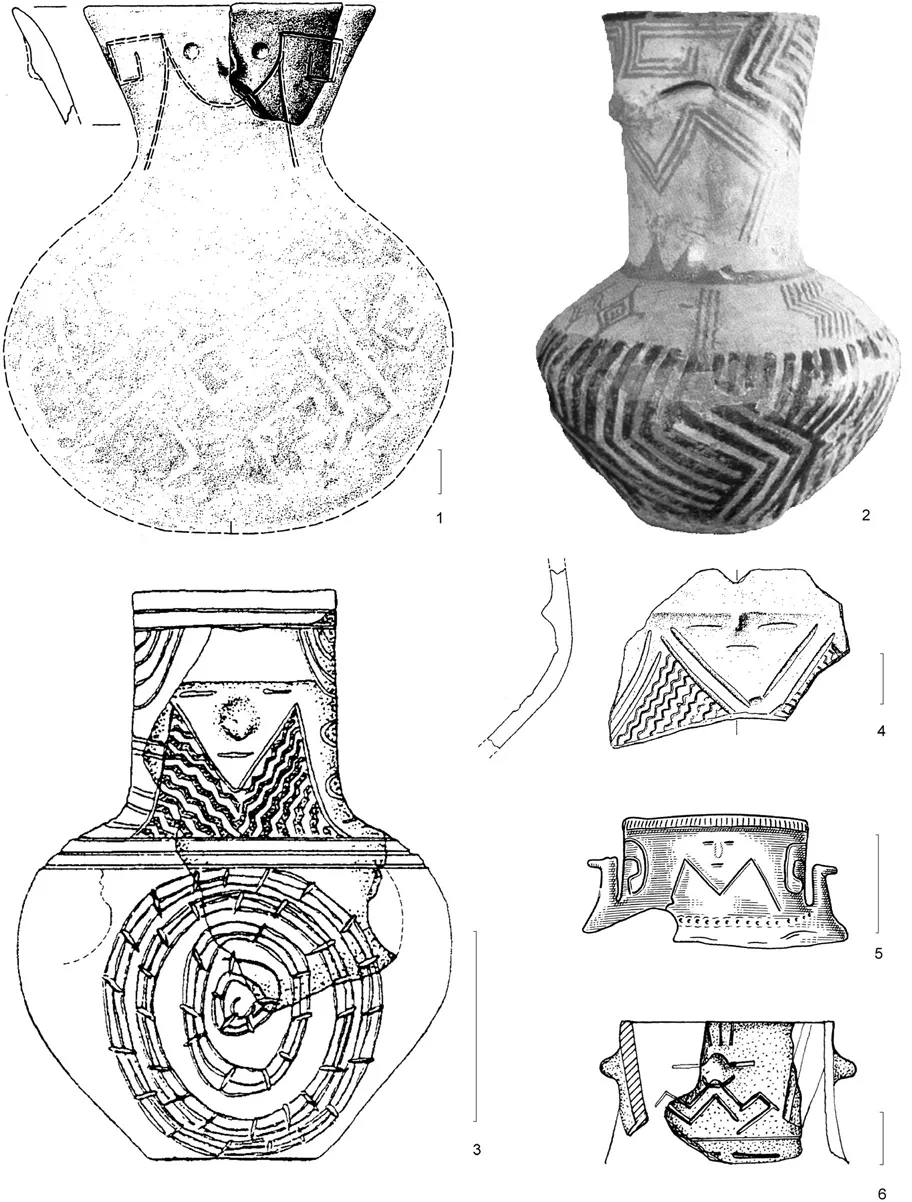

In contrast to figural vessels which bear highly individual features, face vessels and face lids can be classified by general typological as well as by ornamental patterns. Among these motifs are some which reflect the general contemporary spectrum of decoration and embellishment and others which seem to be limited to particular zones of face vessels and lids following clear rules of placement and design (fig. 1; Schwarzberg 2011, 16).

Thomas Link & Joanna Pyzel (Hrsg.)

Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation.

Fokus Jungsteinzeit. Berichte der AG Neolithikum 5. Kerpen-Loogh 2017, 123−145

Fig. 1 Most frequent accompanying motifs on face vessels and anthropomorphic pottery vessels (1 M-Motifs; 2 Inverse Ω-Motifs; 3 Angles; 4 Meanders/Spirals; 5: T-/Y-/П-Motifs; 6 Diagonal Bends; 7 Curves and Angle-Curve-Ornaments; 8 Groups of Lines). – After Schwarzberg 2011.

Except for early examples of the 7th millennium BC from the Near East and a few rather young pieces from LBK and early Lengyel contexts3 that were found in graves, most of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Old World figural vessels are from settlement contexts and were used within a household sphere (Schwarzberg 2011, 182). Though secure contextual analysis is still dissatisfying, it is clear by evidence of differing vessel types and sizes that there must have been differing spheres of function. Putting the anthropomorphic vessels into a general figural background and considering special features, such as a putative symbolic ‘masking’ (Schwarzberg 2010b) as seen in a solid statue from Liubcova-Orniţa with a depicted mask and a (face) vessel in its hand (Schier 2005, Abb. 61), it may be assumed that these vessels might have been used at special social, perhaps ritual events (Schwarzberg 2011, 189–192).

This special character is accented by the presence of recurring pictogram-like signs that appear almost exclusively on figural vessels. These symbols can be easily distinguished from other, decorative, ornamental patterns, anatomical features or attributes of dress and jewelry.

Fig. 2 Face vessels with M-Motifs. 1 Friedberg-Dorheim (after Kneipp 2001); 2 Gradešnica (after Nikolov 1975); 3 Biatorbágy-Tyúkberek (after Virág 1998); 4 Bajč (after Cheben 2001); 5 Kunszentmartón-Jaksor (after Idole 1972); 6 Cîrcea (after Lazarovici et al. 2001).

Pictogram-like signs on figural vessels

M-Motifs

The most significant of these motifs is a mostly incised and sometimes painted M-shaped motif that is mainly situated on the vessel neck right below the face (fig. 2–3,1). The upper angles of the M sometimes reach up and provide a triangular shield-like shape of the face zone. Sometimes other elements, e. g. meanders, are attached to the M-like line. The M-motif is of such evidence that it is possible to identify fragments of face vessels just by its occurrence even in the absence of actual depiction of the face4.

The M-motif is clearly related to the LBK and the most frequent accompanying motif on face vessels in the lower Tisza region and parts of the Danube area in the second half of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th millennium BC (fig. 5). However, it is already known from other earlier sites in SE Europe (e. g. Porodin in South Macedonia or Gradešnica in North Bulgaria [Müller-Karpe 1968, tab. 150; Thraker 2004, 62 fig. 7]), while a slightly changed form is found in a vast area between today’s Greece and Germany. Surprisingly, the earliest examples of M-motifs are already known from LBK contexts not of Southeast but of Central Europe (fig. 4)5. Painted W-like signs from Near Eastern face vessels of the second half of the 7th millennium BC (e. g. Tell es-Sawwan: Schwarzberg 2011, 87–89 tab. 67) cannot be associated with the significantly younger pieces from Central Europe. Moreover, the early flask from Niederhummel in Upper Bavaria with two semicircular eyes shows an amalgamation between an M and an inverted Ω (fig. 4). The SE European vessels with a M-motif, e. g. from Gradešnica and Thespiai (Thraker 2004, 62 fig. 7; Hansen 2007, 504 tab. 200, 9), are of younger date. A large anthropomorphic pithos of Szakálhát type from the eponymous site of Vinča (depth 7,445 m: Vasić 1936, 37 tab. 68; Vinča 2008, 259 fig. 168) has to be regarded as a clear Eastern LBK import (Nikolić/ Vuković 2008, 62, footnote 41). Whereas the M is quite frequent in the Tisza-Danube-area, the ornamentation of the pieces from Moravia and the course of the Elbe River has an intermediate character (Pavlů 1966, 706).

Furthermore, the M-motif can be considered a connecting element of the eastern and the western sphere of the LBK (Simon 2003, 60). Whereas it demarcates the Szakálhát group of the Alföld against the Tiszadob group within the Eastern (Alföld) LBK by presence or absence of such motifs, obvious relationships to the Transdanubian Keszthely-Želiezovce group exist (Hansen 2007, 190; Becker 2011, 274). S. Hansen concludes: “By the triangular shape of the face marked by the outline of the M – proven in East Hungary since the Alföld LBK not only for statues but also for face vessels – it reveals that the LBK face vessels [of the Želiezovce group] can be derived from the Szakálhát group” (Hansen 2007, 298).6

In some cases the M appears in deformed or slightly modified shape, as on an amphora from Močovice where it has a H-like shape (Pavlů 1997/98, 96 fig. 143, 4 tab. 42). Based on such examples, I. Pavlů assumes, with a regional focus, that in some areas on the Danube only reduced M motifs appear while I. Kuzma focuses only on chronological and functional change, observing that such a defor...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation – Bericht über die Sitzung der AG Neolithikum am 16. und 17. April 2012 im Rahmen der 20. Jahrestagung des Mittel- und Ostdeutschen Verbandes für Altertumsforschung e. V. in Brandenburg an der Havel: Thomas Link und Joanna Pyzel

- Zur Nutzungsdauer neolithischer Monumente im südjütischen Raum. Untersuchungen an Grabenwerk und Megalithgräbern in der Region Albersdorf (Dithmarschen): Hauke Dibbern

- Das trichterbecherzeitliche Gräberfeld von Borgstedt: Frühe radiometrische Daten für ein nicht-megalithisches, hölzernes Langbett und einen späteren Dolmen: Franziska Hage

- Demographische Modellbildung als ein Schlüssel zu Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation: Fallbeispiel Neolithisierung Zentral- und Nordwest-Europas: Stephen Shennan, Kevan Edinborough und Tim Kerig

- Macht und Fernbeziehungen im 5. Jahrtausend: Florian Klimscha

- Nordwestanatolien, Balkan und Karpatenbecken im diachronen Vergleich – Kulturkontakt und Kommunikation vom 6.–4. Jt. v.Chr: Raiko Krauß

- Die „Einen“ und die „Anderen“? – Rekonstruktion von Kommunikationsstrukturen auf der Grundlage der Verbreitung von Trichterbechern und Kugelamphoren in Megalithgräbern an Ostsee, Warnow und Peene: Luise Lorenz

- Zwischen Wachstum und Krise. Die Pfyner Kultur am Bodensee: Robin Peters

- A Common Thread? On Neolithic Culture Contacts and Long Distance Communication: Heiner Schwarzberg

- Kulturkontakt und Motivation am Beispiel des Neolithisierungsprozess in der südlichen Mecklenburger Bucht: Laura Thielen

- Intercultural relations in the Neolithic Period in the Vistula and San basins: Renata Zych

- Impressum