![]()

1. Functions and Uses of Textiles in the Ancient Near East. Summary and Perspectives

Catherine Breniquet

The world we live in only allows us to imagine very imperfectly the role material productions played in the past. No doubt certain difficulties are avoided by employing an unacknowledged form of ethnographic comparativism and by reinventing formulae and technical gestures using archaeometry and experimental archaeology. But what of a formerly dynamic society which knew how to invent the practices and analogical connections which give the world its hidden dimension and structure its harmony?

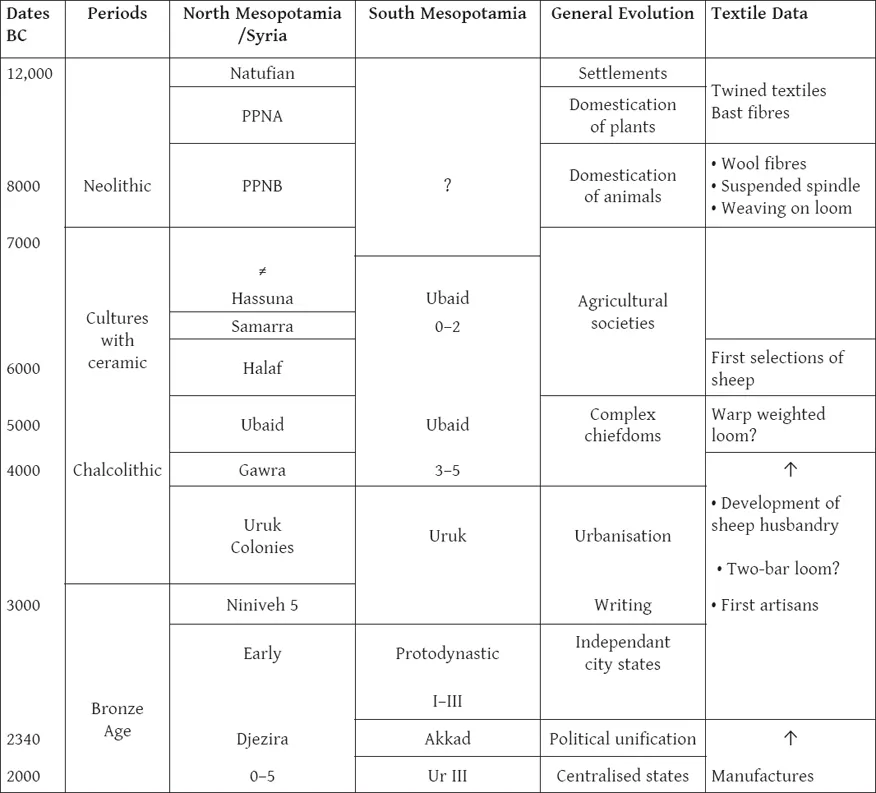

Here, we would like to take the example of textiles, omnipresent and commonplace in our western societies and attempt to detail their use in the Ancient Near East in order to contribute to the development of a critical method using all available sources and a comparative long-term vision. Archaic Mesopotamia will constitute our main framework (Fig. 1.1). Textiles from the region are found in a variety of situations: ritual, economic, political, and practical etc. that are difficult to consolidate under an overarching framework of understanding, but which are however, very closely interlinked. The exceptional roles they play are defined by three connected parameters: their role in kin relationships, their role as a person’s double (for clothing), and their possible monetary role. This leads us to post the question of the origins of textiles, fabrics and clothing.

We deliberately use the term ‘textile’ rather than ‘fabric’. This designates “any fibrous construction” with a certain degree of suppleness and allows us to widen the scope to include assembled bast structures which constitute a form of basket or wickerwork and felt. This approach therefore includes situations in which the prior existence of weaving looms has not been confirmed.1 Finally, the functions are often substituted by uses, as they confine considerations to the utilitarian sphere. Our objective is to draw attention to the informative potential of these material productions and to demonstrate the coherence of Mesopotamian thinking with regard to this.

1. Sources

Due to the historical conditions in which it emerged, and the austerity of the field, the study of Ancient Near Eastern societies is divided into epigraphic studies and archaeological studies. Whilst in practice the trend is for these two branches to come together, it is urgent that more ambitious multi-disciplinary approaches are implemented.2 Given the technical nature of the question, at least six types of sources could be used and compared. It is illusory to search for places where they overlap, they should rather be compared in their historical context, and very often on a case-by-case basis.

Figure 1.1. Chronology. Breniquet 2008, 21.

Archaeological textiles

The first of these sources is direct evidence of textiles, in the form of miraculously preserved fragments, to which indirect evidence may be added, often in the form of imprints onto malleable materials (clay, plaster, bitumen).3 These categories pose major problems in terms of representativeness, as they require an expert eye, adapted excavations and favourable taphonomical conditions to ensure the textiles are both preserved and identified in the field. With the exception of textiles used to wrap (to clothe?) metallic objects, transformed by oxidation, the textiles are most often found in funeral contexts and the use of anthropological methods has made a major contribution to the study of recent finds. Most commonly, these finds are only fragments (clothing, shrouds or strips, goods such as pillows, fabrics laid in tombs, and sometimes several categories at the same time, difficult to distinguish between). To draw a minimum number of conclusions requires detailed, repeated observations in the same context and the identification of recurrent points of comparison across different contexts. This reveals an overrepresentation of plain weaves and, to a lesser extent, twined textiles,4 mainly linen and wool whilst all other fibres are unknown, rendering the conclusions unsafe. It is also very difficult to compare the observations from excavations to textual references, notably when they deal with day-to-day activities, which are not mentioned in the official documentation.5 It is then vital that measures to preserve the remains are taken as quickly as possible, which is often impossible and a large number of isolated observations are made with no ensuing scientific study. The lack of attention paid to multiple cord imprints is also regrettable, notably from the back of sealings.6

Tools

Indirect archaeological documentation (needles, loom weights etc. or installations) may well also provide technical indications of the conditions in which textiles were produced. Once again in this field, the remains are ambiguous in the sense that they are altered over time (or have almost completely disappeared), difficult to identify (unbaked loom weights, for example) and frequently open to several interpretations involving other related techniques (leather or textiles work for example). Generally speaking, it is impossible to interpret such remains in isolation. For example, most woven textiles can be obtained from different installations, which can produce similar textiles. Finally, we tend to look for already known technical categories (horizontal looms, warp-weighted looms) without envisaging other possibilities (backstrap loom, simple wooden frame, boards, needle binding) which are commonly considered not to exist although they have simply not been identified/acknowledged.7

Written sources

As the most common source, the texts available are often solicited. These are divided into official sources drawn up by key authorities, administrative or legal texts, private or public archives. The difficulties they pose have been well documented: The dispersal of cuneiform sources (and the associated bibliographic documentation), the obscurity of ancient classifications, the use of terms which cannot be translated or correlated to an archaeological reality, the use of terms which are too precise or, conversely, too vague, the allusive nature of the mentions made, ancient translations which need revision, patchy information,8 etc. As such the documentation is difficult to grasp, notably when not consulting the primary sources, and it is risky for a textiles specialist to venture unaided into this field of study. However, the essentially economic nature of the cuneiform documentation means that it has an unprecedented potential which has not yet been fully exploited9 with regard to text sources from other relevant ancient periods and cultures.

Iconography

Iconography should be treated as a source in its own right. It provides scenes of people at work, although there are claims to the contrary, mostly based on an old religious interpretation.10 Likewise, iconography provides images of textiles in all types of situation. However, the codification makes them difficult to read: Which objective elements allow us to identify textile as opposed to leather clothing in an image? Questions of representativeness (it is most often official clothing that is represented) and issues which have changed very little over time cloud our perception. It is rare to compare iconography and nomenclature from cuneiform sources.11 Furthermore, details which are technically significant are rare and require an expert eye – and a certain amount of luck – to identify them. For example the stop knot at the join between the side borders and horizontal borders on the skirt of the assistant of the Priest-King on the Uruk Vase which proves the use of a vertical warp-weighted loom (Fig. 1.2). The most em...