eBook - ePub

Dog Behavior

Modern Science and Our Canine Companions

James C. Ha, Tracy L. Campion

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 228 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Dog Behavior

Modern Science and Our Canine Companions

James C. Ha, Tracy L. Campion

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Dog Behavior: Modern Science and Our Canine Companions provides readers with a better understanding of canine science, including evolutionary concepts, ethograms, brain structures and development, sensory perspectives, the science of emotions, social structure, and the natural history of the species. The book also analyzes relationships between humans and dogs and how the latter has evolved. Readers will find this to be an ideal resource for researchers and students in animal behavior, specifically focusing on dog behavior and human-canine relationships. In addition, veterinarians seeking further information on dog behavior and the social temperament of these companion animals will find this book to be informative.

- Provides an accessible, engaging introduction to animal behavior specifically related to human-canine relationships

- Clarifies misunderstandings, mysteries and misconceptions about canines with historical evidence and scientific studies

- Offers insights and techniques to improve human-canine relationships

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Dog Behavior als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Dog Behavior von James C. Ha, Tracy L. Campion im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biological Sciences & Zoology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Biological SciencesThema

ZoologyChapter 1

Dawn of the dog: Evolutionary theory and the origin of modern dogs (Canis familiaris)

Abstract

This chapter provides a brief history of evolutionary theory, including natural and artificial selection, with a focus on the origin of modern dogs (Canis familiaris) to understand the genetic history (“baggage”) and the constraints of the species. The authors examine how humans artificially selected domesticated dogs over many generations, creating almost 200 distinct breeds. This chapter also examines the differences in human co-evolution and social behavior between cats and dogs.

Keywords

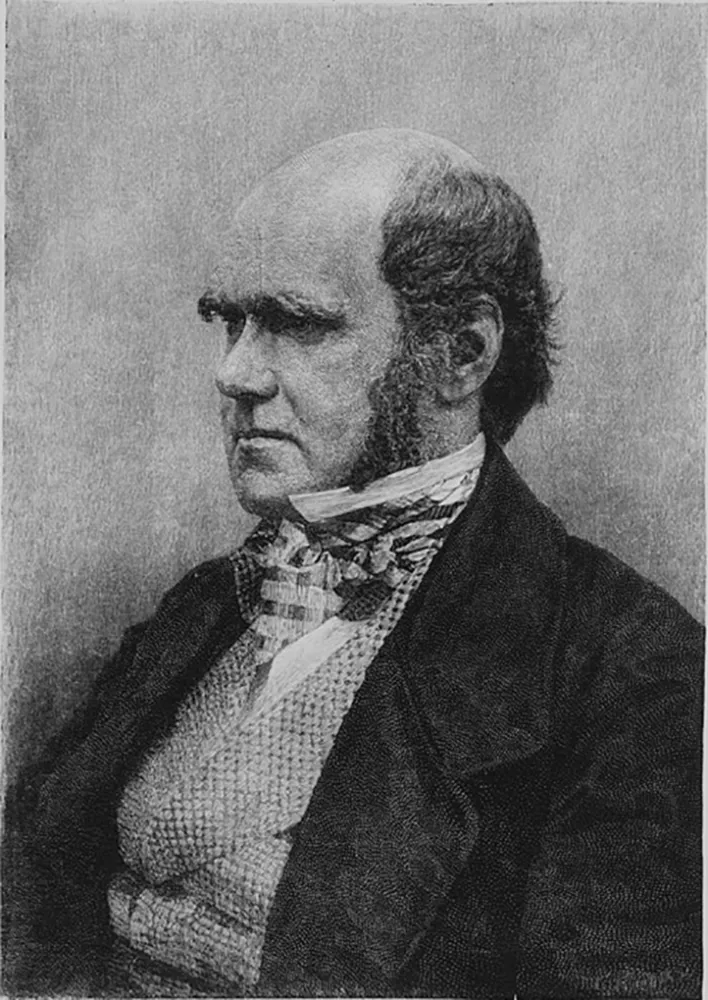

Evolution; Canines; Evolutionary theory; Dogs; Genetic history; Heredity; Breeds; Constraints; Species; Darwin

The Birds and the Beaks

Charles Darwin was fascinated with birds’ beaks and dogs’ skulls – and for good reason. Avian beaks and canine craniums are morphological markers of evolution, exhibiting natural and artificial selection, respectively, and they provided substantial support for Darwin’s groundbreaking theory of evolution – but not necessarily in the way that you may have learned about in school (Fig. 2). “Darwin’s finches” have long been referenced as the catalyst behind his theory of evolution by natural selection – for decades, these geographically isolated avians have been the biological yardstick of choice. When The Origin of Species made its debut in 1859, birds’ beaks were referenced dozens of times, yet there was no mention of the famed finches of the Galapagos – and their varied beak shapes and sizes. Darwin did, however, write at length about the vast physical variety seen among domesticated dogs, which should come as no surprise, as he had 13 different dogs of his own throughout his lifetime. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled on the HMS Beagle as a “gentleman naturalist,” making observations and collecting specimens as the ship made landfall in numerous countries, including Brazil, Patagonia, the Falkland Islands, the Galapagos, Tahiti, New Zealand, and Australia. In September of 1835, the Beagle made landfall in the Galapagos, and it was the unique geography of these islands and the “finches” that lived on them that garnered the most attention from later scientists, including David Lack’s 1947 bestseller, Darwin’s Finches. Darwin did collect dozens of avian specimens from the islands, including finches, but they weren’t the biological epiphany that they’ve been made out to be. It was the mockingbirds (Mimus melanotis) of the archipelago and South America that played a far more important role in his fledgling theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin collected six South American mockingbirds and four Galapagos ones; he saw differences in size, coloration, and beak length among the island birds that were more significant than the differences that he had seen among all of the mockingbirds of South America.

In his 1839 book The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin wrote: “My attention was first thoroughly aroused, by comparing together the numerous specimens, shot by myself and several other parties on board, of the mocking-thrushes, when, to my astonishment, I discovered that all those from Charles Island belonged to one species (Mimus trifasciatus); all from Albemarle Island to M. parvulus; and all from James and Chatham Islands (between which two other islands are situated, as connecting links) belonged to M. melanotis.”10 Based upon those observations from South America and the Galapagos archipelago, Darwin postulated that birds had been shaped by natural selection, where phenotypic11 differences influenced differential reproduction and survival of individuals, with variability in heritable traits arising within populations over time. Darwin noted that each of the four Galapagos mockingbird specimens that he collected from four different islands was exclusively found on each island. He didn’t know it then, but these 19 islands boast the highest level of endemism on earth. Endemism refers to indigenous species that are unique to geographic locations and cannot be found anywhere else on earth. Of the archipelago’s 219 recorded animal species and 600 recorded plant species, 97% of its land mammals and reptiles, 80% of its land birds, and 30% of its plant species are found only in these islands. The Galapagos Islands, which are 600 miles from the nearest landmass, were the perfect place to make observations of isolated species and selective pressures, and thus, evidence of evolution. Perhaps this is why the myth of the Galapagos finches remains such a persistent one. British biologist Julian Huxley stated that it was on these islands that Darwin became “fully convinced that species were immutable – in other words, that evolution is a fact.” While none of this was included in his landmark tome on evolution, Darwin did write about finch evolution in, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage Round the World of H.M.S. Beagle, which was first published in 1836. He wrote:

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends…Unfortunately most of the specimens of the finch tribe were mingled together; but I have strong reasons to suspect that some of the species of the sub-group Geospiza are confined to separate islands. If the different islands have their representatives of Geospiza, it may help to explain the singularly large number of the species of this sub-group in this one small archipelago, and as a probable consequence of their numbers, the perfectly graduated series in the size of their beaks.12

From island to island, the finches and mockingbirds of the Galapagos had noticeable differences with beak size and shape – and in their dietary preferences, as well. Darwin speculated that the ancestors of these birds had arrived on each of the islands many years before, where they were separated by strong winds and tides between the islands and exposed to slightly different environments. These differential selective pressures resulted in birds with certain traits having an advantage – and thus more reproductive success – than others. Over time, four distinct species of mockingbirds and 14 species of finches evolved on the islands, with each differing in its coloration, song, diet, behavior, and beak size and shape. Finches with “parrot-like” beaks specialized in eating buds; birds with grasping beaks specialized in eating insects; birds with probing beaks specialized in eating insects and cactus; and birds with crushing beaks specialized in eating seeds (Fig. 3).

So interested was Darwin with wild birds that after he finished his travels on the Beagle, he took up domestic pigeons, keeping every breed of them that he could obtain. He found the diversity among domesticated birds to be just as astonishing as that of wild ones, given that all of the pigeons had derived from a single wild species, the rock pigeon (Columba livia). Darwin wrote: “Compare the English carrier to the short-faced tumbler, and see the wonderful difference in their beaks, entailing corresponding differences in their skulls…” and that the key to their diversity was “man’s power of accumulative selection: nature gives successive variations, man adds them up in certain directions useful to him…”13

While natural selection was the mechanism behind evolution, Darwin found evidence for artificial selection, as well. The finches and the mockingbirds of the Galapagos had been shaped by natural selection, but the pigeons of Europe had been shaped just as diversely; this time, by humans who had artificially selected them. Humans had artificially selected dogs for generations, as well, intentionally breeding specific individuals with other individuals to preserve or exaggerate certain traits. By favoring novelty and rapidly replicating mutations, humans built dogs with very long (or very short) faces, very short (or very long) legs; dogs with impassive temperaments and dogs who were aggressive; dogs with an excess of wrinkles and dogs with long, silky hair; dogs of every variety. Over time, this resulted in the diverse range of domesticated dog breeds seen today. No other known species, domesticated or free-living, exhibits as much intra-species diversity as the domesticated dog, Canis lupus familiaris. Darwin wrote:

…domestic [dogs] throughout the world…descended from several wild species, [and] it cannot be doubted that there has been an immense amount of inherited variation; for who will believe that animals resembling the Italian greyhound, the blood-hound, the bull-dog, pug-dog, or Bleinhem spaniel – so unlike all wild Canidae – ever existed in a state of nature?... all of our dogs have been produced by the crossing of a few aboriginal species…[and] the possibility of making distinct races by crossing has been greatly exaggerated…14

Just as the beaks of the Galapagos finches indicate their dietary preferences, so does the conformation of each dog breed indicate their predilections. With its long, slender legs and deep chest, the Italian Greyhound is a breed built for speed, while the Bloodhound, with its comparatively more robust skeletal structure and long, ground-gracing ears, is built for stamina and can untiringly track a scent for hours. The muscular, stocky Bulldog was originally bred in England during the 1500s for bull baiting, while the diminutive, brachycephalic (short, broad-skulled) pug was initially bred in ancient China to provide companionship for the Chinese ruling class. Nature had produced successive variations of offspring, and rather than being pruned by natural selection in the wild, man had shaped them up in certain directions that were useful to him (Fig. 4).

Both birds and dogs demonstrate the three conceptual cornerstones of Darwin’s theory: adaptation, descent with modification, and natural selection. With the influence of humans artificially selecting their mates, dogs in particular show the wide range of possibilities of descent with modification. This observation that newer forms were related to, and descended from, earlier forms, was not new15; but Darwin documented the theory of evolution better than anyone who had come before.

More than 150 years after Darwin’s observations, dogs and birds, and every other species, continue to tell the story of evolutionary processes. Wild birds’ varied sizes, colors, and beak shapes provide insight into adaptations, descent with modification, and selective pressures. Evolutionary adaptation is defined as the alteration or adjustment in structure or habits which is hereditary, and by which a species or individual improves its ability to survive and pass on its genes in relationship to the environment.16 Among avians, adaptations include camouflaged feathers, especially with sexually dimorphic17 game birds; and diversified beaks, such as the ones that Darwin saw in the Galapagos mockingbirds and finches. Among canines, adaptations include paws with claws for traction and fleshy pads to provide better support, as well as thick, camouflaging coats with guard hairs that lock out the moisture, keeping them warm during inclement weather.18

Wild birds’ adaptations exhibit the effect of selective pressures such as limited or changing habitat, competition, and predation. Birds also provide a considerable body of evidence for the effects of sexual selection. The peacock, with its “costly” tail, demonstrates that individual success can also depend “not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring…” Females will only choose partners with these ornamental tails, which marks them as healthy, worthy candidates to father their offspring; thus, individuals “differed in structure, color, or ornament…mainly [from] sexual selection.”19

Beyond birds and dogs, well-known stories of other species’ adaptations illustrate the power of selective pressures. A classic example is a case of industrialized melanism with the peppered moth (Biston betularia) in the United Kingdom. At the dawn of the industrial revolution, darker gray peppered moths were relatively rare, but as the revolution progressed over a 45-year span, lichens on the trees died and the trees became stained with soot. The lighte...