eBook - ePub

Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities

Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood, Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 597 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities

Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood, Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This unique book synthesizes the ongoing long-term community ecology studies of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. The studies have been conducted from deserts to rainforests as well as in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats and provide valuable insight that can be obtained only through persistent, diligent, and year-after-year investigation.

Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities is ideal for faculty, researchers, graduate students, and undergraduates in vertebrate biology, ecology, and evolutionary biology, including ecology, natural history, and systematics.

- Provides unique perspectives of community stability and variation

- Details the influence of natural and other perturbations on community structure

- Includes synopses by well-known authors

- Presents results from a broad range of vertebrate taxa

- Studies were conducted at different latitudes and in different habitats

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities von Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood, Martin L. Cody, Jeffrey A. Smallwood im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biological Sciences & Ecosystems & Habitats. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Biological SciencesCHAPTER 1

Introduction to Long-Term Community Ecological Studies

MARTIN L. CODY, Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095

I. Introduction

I. Contents of the Book

References

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Background

In view of the wide disparity of approaches among ecologists to their science, it is notable that considerable concordance exists in at least one respect: long-term studies are widely regarded as indispensable, and thus no elaborate case need be made for their justification. The potential for change in the populations that make up a local biota and its various assemblages and communities is an accepted fact and is compelling in its many sources. Some of the potential comes directly from variability in abiotic factors, such as climatic trends over the longer term, or in weather variations from year to year in the mid to shorter terms. Some will come indirectly from such abiotic factors, as they influence species’ geographic ranges and lead to expansion or contraction; thus, at the local level some populations are favored at the expense of others as conditions for their persistence or increase are enhanced. Yet other factors for long-term change are strictly intrinsic to organisms, as they adapt and evolve and thereby occupy ecological roles in a specific area or at a given site that change or shift over time. And overall, inexorable and perhaps inevitable, is the increasing pressure on environments and habitats from human activities, providing a potential for biotic change that can be ignored only in very few circumstances. Thus, the nature, causes, and effects of variability in ecological systems can be understood only through extended study over far longer time periods than those typical of many sciences and of most other biological sciences.

Clearly, with a longer research commitment the capacity to resolve shortterm phenomena is enhanced, and the possibilities for discovering and addressing those of longer term are revealed. As Gilbert White, the astute and dedicated natural historian of his southern English parish, remarked in 1779, “It is now more that forty years that I have paid some attention to the ornithology of this district, without being able to exhaust the subject; new occurrences still arise as long as any inquiries are kept alive” (White, 1877). Calls for the investment of more time, effort, and resources in long-term ecological studies have become much more persistent over the last decade or so. They appear attributable to a recognition of two rather distinct aspects of ecology, the dynamical nature of ecological systems themselves and the uses to which our understanding of the systems might be put.

First, there is the recognition that ecological processes are, innately, of longterm resolution and that change is as justifiably a quality of ecological systems as is permanence or stability. Many sorts of natural perturbation or disturbance are rare and/or aperiodic, and their effects may persist for centuries or longer. And many ecological processes, such as natural succession, the outcome of competition for limited resources, or the cycling of predator-prey systems, may take inordinately long times for documentation let alone resolution, even without persistent disturbance. Thus with an overlay of variability from abiotic factors, from long-term climatic change to shorter term variations in weather, and from inevitably pervasive anthropogenic influences, it is apparent that many ecological questions require an unusual commitment of research effort.

Second is the need for and dependence upon long-term data bases in the management of critical species, habitats, and resources. This need is often promoted by the legal aspects of species conservation and resource exploitation and becomes apparent only when the letter of such legislation is followed. Resource managers, whether of large animals in small national parks, of habitatspecialized kangaroo rats or gnatcatchers facing urban development, or of desert landscapes faced with large-scale mining concerns, inevitably conclude that their data bases are deficient and that their capacity for prediction or extrapolation is limited.

Several indicators of the importance and perceived value of long-term studies are visible. An overview of the strategic or policy aspects of conducting and funding long-term studies is given in Long-Term Ecological Research (SCOPE—Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment—Volume 47, Risser, 1991), and implicit in the imperatives for monitoring our dwindling resources is the realization that such monitoring efforts will be ongoing, likely to become an essential part of environmental management in perpetuity (e.g., Spellerberg, 1991). Long-Term Studies in Ecology (Likens, 1989) resulted from the 2nd Cary Conference, which identified a “critical need” for commitment to a longer-term approach and adopted a statement reading, in part:

Sustained ecological research is one of the essential approaches for developing [an] understanding [of] processes that vary over long periods of time. However, to fulfill its promise, sustained ecological research requires a new commitment on the part of both management agencies and research institutions [and] should include longer funding cycles, new sources of funding, and increased emphasis and support from academic and research institutions.

The US/LTER (Long-Term Ecological Research) program, instigated in 1977, addresses these needs (Callahan, 1991), but its aims for representative sites in major North American biomes have yet to be met.

B. Ecological Studies over Spatial versus Temporal Scales

There has been a good deal of attention in the ecological literature paid to the notion of scale (e.g., Wiens et al., 1986, for an overview), which has dual spatial and temporal aspects. However, much of the development of the concept has addressed the spatial rather than the temporal concerns, leading, among other important aspects, to treatment of populations in fragmented habitats as “meta-populations” (e.g., Hastings and Wolin, 1989) and their associations in the patches as “metacommunities” (Wilson, 1992). Models that emphasize spatial structure already have a considerable history, beginning with the work of Levins (1969, 1970), Levins and Culver (1971), Horn and MacArthur (1972), and Yodzis (1978); their implications for genetics, predation (Kareiva, 1986), competition and coexistence (e.g., Chesson, 1986), diversity (e.g., Hanski et al., 1993), and conservation (e.g., the MVP—Minimum Viable Population—problem, Gilpin and Soulé, 1986) are profound. Levin’s (1992) perspective of these developments and their Significance is particularly valuable.

A corresponding theoretical development of temporal analogs of models with spatial heterogeneity seems lacking in the literature. In the same way that a greater understanding of communities in patchy and spatially heterogeneous habitats is gained from studies with a broader, more regional perspective than from single, site-specific snapshots, so it is with communities that experience environmental heterogeneity over time. The broader perspective that comes from long-term research contributes to the understanding of how communities cope with year-to-year, and decade-to-decade, variations in conditions at a particular site.

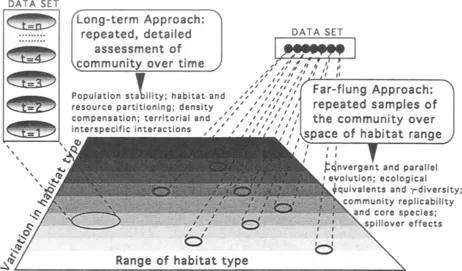

A diagrammatic comparison of temporal versus spatial scale broadening is given in Fig. 1, but the duality of the two scales is exacerbated by their obvious qualitative differences. Logistically, a broadening of perspective in spatial scales can be achieved relatively easily, with adjustments that might take advantage of, e.g., further site replication, wider habitat gradients, a better microscope, or better satellite imagery, but there is not such a ready correction for restricted temporal scales: time alone can serve to broaden a data base in the temporal dimension. Specifically with respect to questions of community structure, stability, and replicability, there are advantages and disadvantages to broadening scales in the spatial versus temporal dimensions, the “far-flung” versus the “long-term” approach. By replicating sites within a limited time over the geographical range of a habitat (Fig. 1, left–right axis), more habitat variability is likely to be encountered (front–back axis), and the precision of intersite comparisons reduced. However, questions of convergent and parallel evolution can be addressed, as geographic counterparts may substitute in distant sites, and the effects and influences of species from adjacent (different) habitats (spillover effects, mass effects; Shmida and Ellner, 1984, Cody, 1993, 1994) can be evaluated, because throughout a habitat’s range the extent and type of other habitats will likely vary. The long-term approach will lack these potential advantages, but also lack the disadvantage of establishing replicability (e.g., in terms of habitat structure) over multiple sites.

FIGURE 1 Diagrammatical representation of two different views of extended community-level studies, contrasting the far-flung approach, in which sites are replicated over space, with the longterm approach, in which a Single site is studied over an extended time period. See text for discussion.

However, at a single site studied over a longer term, site stability is by no means assured; indeed, site-specific variation over time can be dramatic and, if calibrated, can allow...