![]()

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

The oceans occupy about 71% of the Earth’s surface. The deepest parts of the seafloor are almost 11 000 m from the sea surface, and the average depth of the oceans is about 3800 m. The total volume of the marine environment (about 1370 × 106 km3) provides approximately 300 times more space for life than that provided by land and freshwater combined. The name given to our planet, ‘Earth’, is a synonym for dry land, but it is a misnomer in that it does not describe the dominant feature of the planet — which is a vast expanse of blue water.

The age of Earth is thought to be about 4600 million years. The ocean and atmosphere formed as the planet cooled, some time between 4400 and 3500 million years ago, the latter date marking the appearance of the first forms of life (see the Geologic Time Scale, Appendix 1). The earliest organisms are believed to have originated in the ancient oceans, many millions of years before any forms of life appeared on dry land. All known phyla (both extinct and extant) originated in the sea, although some later migrated into freshwater or terrestrial environments. Today there are more phyla of animals in the oceans than in freshwater or on land, but the majority of all described animal species are non-marine. The difference in the number of species is believed to be due largely to the greater variety of habitats on land.

1.1 SPECIAL PROPERTIES AFFECTING LIFE IN THE SEA

Why should life have arisen in the sea, and not on land?

Marine and terrestrial environments provide very different physical conditions for life. Seawater has a much higher density than air, and consequently there is a major difference in the way gravity affects organisms living in seawater and those living in air. Whereas terrestrial plants and animals generally require large proportions of skeletal material (e.g. tree trunks, bones) to hold themselves erect or to move against the force of gravity, marine species are buoyed up by water and do not store large amounts of energy in skeletal material. The majority of marine plants are microscopic, floating species; many marine animals are invertebrates without massive skeletons; and fish have small bones. Floating and swimming require little energy expenditure compared with walking or flying through air. Overcoming the effects of gravity has been energetically expensive for terrestrial animals, and perhaps it should not be surprising that the first forms of life and all phyla evolved where the buoyancy of the environment permitted greater energy conservation.

Two other features of the ocean are especially conducive to life. Water is a fundamental constituent of all living organisms, and it is close to being a universal solvent with the ability to dissolve more substances than any other liquid. Whereas water can be in short supply on land and thus limiting to life, this is obviously not the case in the marine environment. Secondly, the temperature of the oceans does not vary as drastically as it does in air.

On the other hand, certain properties of the sea are less favourable for life than conditions on land. Plant growth in the sea is limited by light because only about 50% of the total solar radiation actually penetrates the sea surface, and much of this disappears rapidly with depth. Marine plants can grow only within the sunlit surface region, which extends down to a few metres in turbid water or, at the most, to several hundred metres depth in clear water. The vast majority of the marine environment is in perpetual darkness, yet most animal life in the sea depends either directly or indirectly on plant production near the sea surface. Marine plant growth is also limited by the availability of essential nutrients, such as nitrates and phosphates, that are present in very small quantities in seawater compared with concentrations in soil. On land, nutrients required by plants are generated nearby from the decaying remains of earlier generations of plants. In the sea, much decaying matter sinks to depths below the surface zone of plant production, and nutrients released from this material can only be returned to the sunlit area by physical movements of water.

The greatest environmental fluctuations occur at or near the sea surface, where interactions with the atmosphere result in an exchange of gases, produce variations in temperature and salinity, and create water turbulence from winds. Deeper in the water column, conditions become more constant. Vertical gradients in environmental parameters are predominant features of the oceans, and these establish depth zones with different types of living conditions. Not only does light diminish with depth, but temperature decreases to a constant value of 2–4°C, and food becomes increasingly scarce. On the other hand, hydrostatic pressure increases with depth, and nutrients become more concentrated. Because of the depth-related changes in environmental conditions, many marine animals tend to be restricted to distinctive vertical zones. On a horizontal scale, geographic barriers within the water column are set by physical and chemical differences in seawater.

Much of this text deals with descriptions of marine communities and the interactions between physical, chemical and biological properties that determine the nature of these associations. Some attention is also given to the exploitation of marine biological resources. Despite the fact that the oceans occupy almost three-quarters of the Earth’s surface, only 2% of the present total human food consumption comes from marine species. However, this is an important nutritional source because it represents about 20% of the high-quality animal protein consumed in the human diet. Although a greater total amount of organic matter is produced annually in the ocean than on land, the economic utilization of the marine production is much less effective. One branch of biological oceanography, fisheries oceanography, is a rapidly developing field that addresses the issue of fish production in the sea.

1.2 CLASSIFICATIONS OF MARINE ENVIRONMENTS AND MARINE ORGANISMS

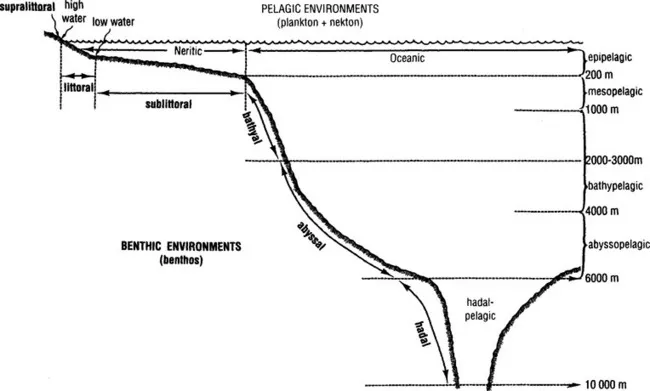

The world’s oceans can be subdivided into a number of marine environments (Figure 1.1). The most basic division separates the pelagic and benthic realms. The pelagic environment (pelagic meaning ‘open sea’) is that of the water column, from the surface to the greatest depths. The benthic environment (benthic meaning ‘bottom’) encompasses the seafloor and includes such areas as shores, littoral or intertidal areas, coral reefs, and the deep seabed.

Another basic division separates the vast open ocean, the oceanic environment, from the inshore neritic zone. This division is based on depth and distance from land, and the separation is conventionally made at the 200 m depth limit which generally marks the edge of the continental shelf (Figure 1.1). In some areas like the west coast of South America where the shelf is very narrow, the neritic zone will extend only a very slight distance from shore. In other areas (e.g. off the north-east coast of the United States), the neritic zone may extend several hundred kilometres from land. Overall, continental shelves underlie about 8% of the total ocean, an area equal to about that of Europe and South America combined.

Further divisions of the pelagic and benthic environments can be made which divide them into distinctive ecological zones based on depth and/or bottom topography. These will be considered in later chapters.

Marine organisms can be classified according to which of the marine environments they inhabit. Thus there are oceanic species and neritic species depending upon whether the organisms are found in offshore or coastal waters, respectively. Similarly, plants or animals that live in association with the seafloor are collectively called benthos. The benthos includes attached seaweeds, sessile animals like sponges and barnacles, and those animals that crawl on or burrow into the substrate. Additional subdivisions of the benthos are given in Chapter 7.

The pelagic environment supports two basic types of marine organisms. One type comprises the plankton, or those organisms whose powers of locomotion are such that they are incapable of making their way against a current and thus are passively transported by curr...