![]() RISK AND RETURN

RISK AND RETURN![]()

RISK AND RETURN

John H. Cochrane and Tobias J. Moskowitz

While early efficient market work could start with the working hypothesis that expected returns are constant over time, the need for risk adjustment and a “model of market equilibrium” is immediately apparent in the cross-section. There are stocks whose average returns are greater than those of other stocks. But are the high-average-return assets really riskier in the ways described by asset pricing models?

This empirical work is not easy. It took lots of thought and creativity between writing down the theory and evaluating it in the data. The four papers in this section are not only a capsule of how understanding of the facts developed. They more deeply show how Gene, alone, with James MacBeth first, and with Ken French later, shaped how we do empirical work in finance.

FAMA AND MACBETH

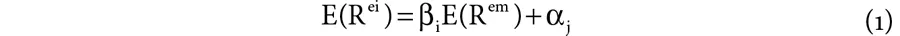

The CAPM, the subject of Fama and MacBeth’s famous paper, states that average returns should be proportional to betas,

where the betas are defined from the time-series regression

Here, Rtei is the excess return of any asset or portfolio i, and Rtem is the excess return of the market portfolio.

You run regression (2) first, over time for each i to measure the betas. Then the CAPM relationship (1) says average returns, across i, should be proportional to the betas, with “alphas” as the error term (i.e., the average returns not explained by the model). Though unconventional, we write the alphas as the last term in (1) to emphasize that they are errors to the relationship.

Now, an empiricist faces many choices. First, one could apply this model to data by just running the time-series regression (2). The mean market premium, the betas, and the alphas are all then estimated, and one can see if the alphas are small.

Fama and MacBeth didn’t do that. They estimated the cross-section (1) in a second stage. Why? For many good reasons. First, they wanted, we think, to get past formal estimation and generic testing to see how the model behaves in all sorts of intuitive ways. Sure, all models are models, as Gene frequently reminds us, and all models are false. But even if a glass is statistically 5% empty, we want to really understand the 95%.

The paper tries a nonlinear term in beta in (1), idiosyncratic variances, an intercept, and so forth. These are natural explorations of ways that the model might plausibly be wrong. To explore them, we need to run the cross-sectional regression.

Second, betas are poorly estimated, and betas may vary over time. Fama and MacBeth use portfolios to estimate betas, which reduces estimation error. Portfolios, however, also reduce information, in this case cross-sectional dispersion in betas. (It’s like measuring your income by measuring the average income on your block.) Fama and MacBeth used portfolios that maintained dispersion in true betas while also reducing estimation error. They sorted stocks into portfolios based on the stocks’ historical betas, but then used the subsequent, post-ranking portfolio beta in the regression equation (2). As is typical with Gene’s papers, there is a deep understanding of a complicated problem, solved in a simple yet clever way.

The cross-sectional regression framework easily allows one to use rolling regressions (2) so betas can vary over time.

Forty-five years of econometrics later, we know how to estimate models with time-varying betas, and we know other ways to handle the errors-in-variables problem too. But the transparency and simplicity of the Fama-MacBeth approach still reigns.

The use of portfolios itself is a foundational choice in empirical work. In this paper, you see tables with 1 to 10 marching across the top. That isn’t in the theory, which just talks about generic assets. And it isn’t in formal econometrics either. (Formal econometrics might call it nonparametric estimation with an inefficient kernel.) Yet this is how we all do empirical finance. It is useful and intuitive.

Most famously, Fama and MacBeth dealt with the problem that the errors are correlated across assets. If Ford has an unusually good stock return this month, it’s likely GM has one too. Therefore, the usual formulas for standard errors and tests, which assume observations are uncorrelated across companies as well as over time, are wrong.

This was 1970, before the modern formulas for panel data regressions were invented. Fama and MacBeth found a brilliant way around it, by running a cross-sectional regression at each time period and using the in-sample time-variation of the cross-sectional regression coefficients to compute standard errors. In doing so, they allow for arbitrary cross-correlation of the errors. That this procedure remains in widespread use, despite the existence of econometric formulas that can deal with the problem—sometimes successfully, and sometimes not—is a testament to how brilliant the technique was.

More deeply, Fama and MacBeth’s approach to cross-correlation was not to adopt GLS or other statistically “efficient” procedures, which every econometrics textbook of the day and up to just a few years ago would advocate, but instead to run robust, reliable OLS regressions and compute corrected standard errors. That practice has since spread far and wide.

Finally, the Fama and MacBeth procedure has a clever portfolio interpretation. The coefficient in the regression of returns on betas represents the return to a portfolio that has zero weight, unit exposure to beta, and is minimum variance among all such portfolios that satisfy the first two constraints. This description is in essence the market portfolio. Hence, an average of this portfolio’s returns is an estimate of the market risk premium. Since returns are close to uncorrelated over time, this interpretation justifies the standard error of that mean return as the standard error of the Fama-MacBeth regression coefficient.

This beautiful insight would allow future researchers to look at other characteristics and other betas in the same way: the coefficients associated with other characteristics (e.g., size or book-to-market ratios) or betas on the right-hand side of the regression are minimum-variance returns of zero cost portf...