![]()

Chapter One

Josef Albers and The Ethics of Perception

Experimentation means learning by experience.

Josef Albers, 19411

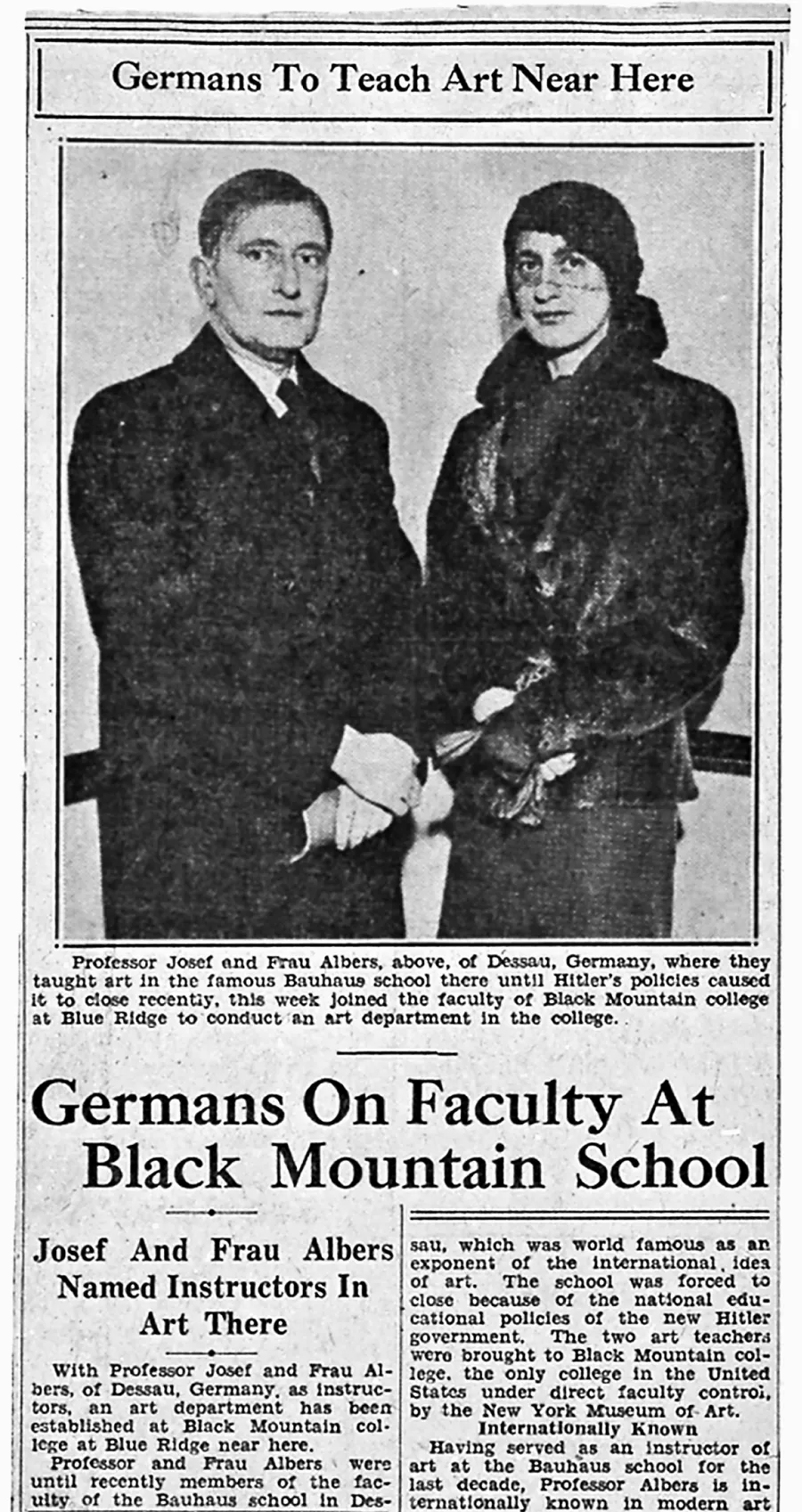

A most poignant document of Black Mountain College’s early years is the snapshot of Josef and Anni Albers’s arrival, published in North Carolina’s Asheville Citizen on December 5, 1933 (fig. 1.1). “Germans to Teach Art Near Here,” the caption reads, though “Fresh Off the Boat” would do just as well; the grainy newsprint depicts the couple posed tensely in formal attire—he in tie and jacket, she in fur, cloche, and veil. Tightly angled in a corner, they look very much the anxious, recent immigrants. While Anni’s mild gaze seeks out the viewer, Josef averts his eyes, his stiff bearing and tightly clasped hands registering trepidation, even strain. Fleeing the Nazi regime, the couple left Berlin for the site of a newly founded experimental school in rural Appalachia, a quite improbable relocation under other circumstances. Though they came from the Bauhaus, one of the most radical art institutions of the era, to what was vociferously announced as its successor in the United States, this evidence of a nervous arrival is testimony to their unexpectedly providential exile from Europe.

Josef knew but a few words in English, though Anni was fluent. In their first years, she would serve double duty as both faculty member at the recently founded college and as his patient translator. The newspaper article does not mention this, nor does it quote his famous response to their welcoming ceremony. Rallying his scant English when asked what he hoped to accomplish in the United States, Josef declared simply, “I want to open eyes.”2 Typical of his plain and frank manner, Albers’s pronouncement nonetheless encapsulates two concerns that characterize his years in the United States. Most obviously, it indicates the centrality of his pedagogical commitment (the same newspaper article proclaimed Albers as “internationally known . . . for his unusual method of art instruction”). His statement also foregrounds the preeminence of a study of vision in his pedagogy and in Bauhaus teaching more generally—it is eyes he wants to open, after all.3 Pedagogy and vision: together, his words represent a desire to craft an audience for abstraction and, more particularly, for his art, an audience that would be tutored in the perceptual strategies he was developing in his teaching.

Figure 1.1 “Germans on Faculty At Black Mountain School,” Asheville (NC) Citizen, December 5, 1933. Photograph by Tim Nighswander. Courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / The Asheville Citizen-Times.

The key elements of these perceptual strategies were set out in Albers’s three-pronged Preliminary Course, or Vorkurs, brought from the Bauhaus to Black Mountain and later to Yale University. In these drawing, color, and design classes, he proposed an ordered and disciplined testing of the various qualities and appearances of readily available materials such as construction paper and household paint samples. His approach brought out the correlation between formal arrangement and underlying structure, and placed a high value on economy of labor and resources. He stressed the experience, rather than any definite outcomes, of a laboratory educational environment and promoted forms of experimentation and learning in action that could dynamically change routine habits of seeing.4 He began his drawing and design courses with mirror writing, a simple exercise in defamiliarization. He invited students to draw their names, for example, backward and in cursive, as if reflected in a mirror, and then asked them to render this script using their nondominant hand. Drawing by automatic motor sense invariably becomes a crutch, overwriting any direct consciousness of how the actual forms of a signature are produced. Mirror exercises provided students with a sure way to begin challenging sterile habits of observation, “to develop awareness of what we do out of habit as opposed to choice.”5

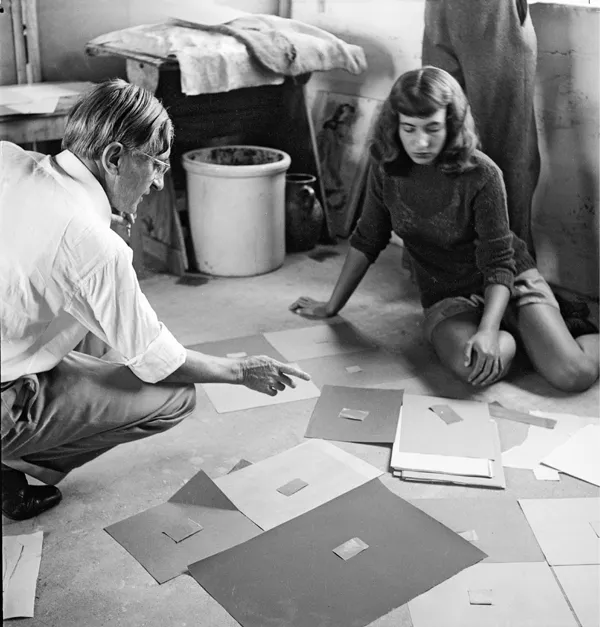

Figure 1.2 Josef Breitenbach, Josef Albers’ Color Class, Summer 1944. Gelatin silver photograph © The Josef and Yaye Breitenbach Charitable Foundation, New York. Courtesy The Josef Breitenbach Archive, Center For Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson.

To grasp Albers’s proposal of what he came to term a “new visual expression” through acts of experimentation, it is crucial to understand the discursive field he produced around geometric abstraction, that is, how he explained the importance of a continuous study of the constitutive elements of form.6 The first section of this chapter will undertake a close reading and analysis of Albers’s large body of unpublished texts written in his budding English, which can shed light on the process of testing variations in form that his pedagogical strategies elaborated. (One could argue that given its minimal denotation of form and its refusal of naturalistic representation, geometric abstraction always relied heavily on discursive interpretations, offered both in the artists’ own writings and by critics.) He redesigned the experience of looking at art as one of “direct seeing,” whereby attention to perceptual habits marks routine cognitive associations as social constructions and allows these associations to be influenced and possibly transformed.7 In that vein, the second section of this chapter will connect Albers’s pedagogy with his own work. With careful study of his sketches, studies, and paintings undertaken at Black Mountain (and a few from his subsequent decades in the United States), it will be possible to address how Albers developed methods of articulating form that highlighted its contingency and endless mutability.

The final section of this chapter will explore how Albers went further to find in form an ethics of perception, which he developed in theories of progressive pedagogy concerning experimentation and social change. Drawing on the work of John Dewey, Albers presented the methodology of the experimental test as a forceful corrective against stagnant perceptual habits in the culture at large, bringing attention to the tremendous stake of progressive education in combating forces of social reproduction, that is, the tendency of dominant cultural values to be reproduced as the privileged traditions of a society. He maintained that learning to observe and design form made an essential contribution toward cultural transformation and growth. In brief, in Albers’s ethics of perception, careless habits—habits that inhibit self-actualization and social progress—can be overcome with the disciplined study of the constitution of forms, forms that themselves compose the ubiquitous, though often overlooked, material and appearance of our surroundings.

PERCEPTION BETWEEN SCIENCE AND INTUITION

Elements of Josef Albers’s teachings have become so familiar and ingrained in current art curricula that it is difficult to recall how radically art education was altered by the widespread adoption of his methods. Developed at the Bauhaus in the early 1920s through 1933 and continued at Black Mountain College from 1933 to 1949 and at Yale from 1950 to 1958, Albers’s Preliminary Course consistently challenged conventional art teaching. Indeed, it is important to remember the great influence of Black Mountain’s teaching methods generally—especially during Albers’s nearly two decades at the College—in positioning invention and experiment as central elements of educational practice in the United States, and to bear in mind that in the years preceding its implementation elsewhere, “it was heresy,” according to Albers, “to consider art a central part of a college curriculum or a means of general education.”8

Visual arts training in the early twentieth century, in Europe as in the United States, took place in specialized art academies modeled on classical Beaux-Arts instructional models or in technical institutes featuring drawing for industrial design, rather than in liberal arts colleges such as Black Mountain. In academies, distinctions among various media were reinforced, and the rendering from life, above all the study of the nude, was central. The emphasis was on repetition (in life studies) and duplication (in copying past works). Advancement was secured by a review process that paradoxically assessed a pupil’s fidelity to precursors and his (rarely her) departure from precedent in an “original” work—the academy study of the male nude. In its technical application, drawing accentuated the repeatability of objective nature by creating a strict geometry of form (and in this sense, to use M. Norton Wise’s phrase, “drawing is the language of engineering”).9 This language of reproduced form, as Molly Nesbit contends, was routinized by drills in elementary and higher education toward “blueprints of production” in industrial product design.10 Even attempts to devise hybrid guild-workshop models of art education spawned by the Arts and Crafts movement, as Howard Singerman has noted, tended to attach more importance to craft traditions than to creative work in art and design.11 Whatever the model—academy, technical college, or workshop—visual art training beyond high school was not closely integrated with liberal arts concerns or with experimental or progressive approaches.

Albers bemoaned the persistence of such models in the United States:

I believe dominating education methods in this country are not at all typically American with their stereotyped requirements, standardized curricula and mechanized evaluation of achievements. Why do we still have the belief in academic standards while our living reveals variety, youth and freshness . . . ? Why must exploration and inventiveness, two American virtues, too, play such a minor part in our schools?12

He found particularly grating the assumption in standardized art education that talent and an aptitude for art were inherent gifts and prerequisites to creativity. Instead, he fostered a general training in the fundaments of art as “more democratic [and] . . . giving a chance to many more people,” not just to the exceptional or advanced student.13 In this sense, Albers was a good fit for Black Mountain; the centrality of art education was emphasized in the College’s 1933 inaugural publication shortly before his arrival: “Fine Arts, which often exist precariously on the fringes of the curriculum, are regarded as an integral part of the life of the College and of importance equal to that of the subjects that usually occupy the center of the curriculum.”14 The goal was not to produce professional artists but to consider all individuals as possible creators and to offer training for what Albers termed a “flexible and productive mind that wants to do something with the world . . . we are on the way to the researcher, discoverer, to the inventor, in short to the worker who produces or understands revelations.”15

Art practice offered the ideal site in culture from which to encourage broad-minded thinking, as training in experimentation steered a course toward “coordination, interpenetration . . . conclusions, new viewpoints . . . for developing a feeling or understanding for atmosphere and culture.”16 The as yet unrealized prospect of education thus could consist of a richer understanding of “action or life,” not a stockpiling of mere information or knowledge.17 Developing an attuned visual sensibility involved testing, dynamism, and action, not the passivity and stasis of education based on study of precedent alone.18 Albers’s series of foundational courses promoted independent thinking and a close study of the mutable nature of form. On a visit to Black Mountain in 1944, Walter Gropius praised Albers’s innovation: “He has discarded the old procedure to hand over to the student a ready-made formulated system. He gives them instead objective tools that enable them to dig into the very stuff of life. . . . This ever-changing approach seems to me pregnant of life, present and future.”19

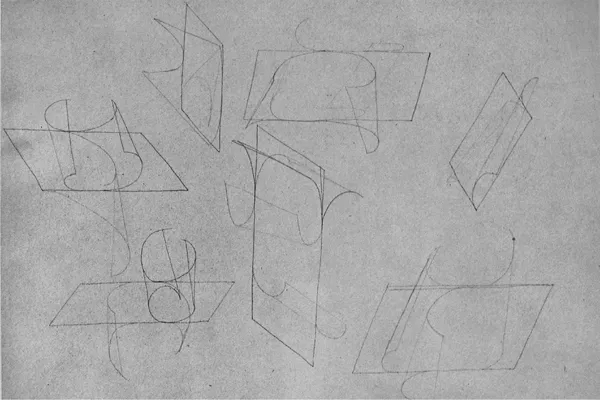

Figure 1.3 Unknown artist, Drawing Study, n.d. Reproduced in J. Albers, Search Versus Re-Search (Hartford, CT: Trinity College Press, 1969), 51. © Trinity College Trustees. Courtesy of the Watkinson Library, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut.

Albers’s battery of courses constituted a broad foun...