eBook - ePub

The Tragic Sense of Life

Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought

Robert J. Richards

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The Tragic Sense of Life

Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought

Robert J. Richards

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Prior to the First World War, more people learned of evolutionary theory from the voluminous writings of Charles Darwin's foremost champion in Germany, Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), than from any other source, including the writings of Darwin himself. But, with detractors ranging from paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould to modern-day creationists and advocates of intelligent design, Haeckel is better known as a divisive figure than as a pioneering biologist. Robert J. Richards's intellectual biography rehabilitates Haeckel, providing the most accurate measure of his science and art yet written, as well as a moving account of Haeckel's eventful life.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The Tragic Sense of Life als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The Tragic Sense of Life von Robert J. Richards im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biological Sciences & Science General. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Biological SciencesThema

Science GeneralCHAPTER ONE

Introduction

In late winter of 1864, Charles Darwin received two folio volumes on radiolarians, a group of one-celled marine organisms that secreted skeletons of silica having unusual geometries. The author, the young German biologist Ernst Haeckel, had himself drawn the figures for the extraordinary copper-etched illustrations that filled the second volume.1 The gothic beauty of the plates astonished Darwin (see, for instance, plate 1), but he must also have been drawn to passages that applied his theory to construct the descent relations of these little-known creatures. He replied to Haeckel that the volumes “were the most magnificent works which I have ever seen, & I am proud to possess a copy from the author.”2 A few days later, emboldened by his own initiative in contacting the famous scientist, Haeckel sent Darwin a newspaper clipping that described a meeting of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians at Stettin, which had occurred the previous autumn. The article gave an extended and laudatory account of Haeckel’s lecture defending Darwin’s theory.3 Darwin immediately replied in a second letter: “I am delighted that so distinguished a naturalist should confirm & expound my views; and I can clearly see that you are one of the few who clearly understands Natural Selection.”4 Darwin recognized in the young Haeckel a biologist of exquisite aesthetic sense and impressive research ability and, moreover, a thinker who obviously appreciated his theory.

Haeckel would become the foremost champion of Darwinism not only in Germany but throughout the world. Prior to the First World War, more people learned of evolutionary theory through his voluminous publications than through any other source. His Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (Natural history of creation, 1868) went through twelve German editions (1868–1920) and appeared in two English translations as The History of Creation. Erik Nordenskiöld, in the first decades of the twentieth century, judged it “the chief source of the world’s knowledge of Darwinism.”5 The crumbling detritus of this synthetic work can still be found scattered along the shelves of most used-book stores. Die Welträthsel (The world puzzles, 1899), which placed evolutionary ideas in a broader philosophical and social context, sold over forty thousand copies in the first year of its publication and well over fifteen times that during the next quarter century—and this just in the German editions.6 (By contrast, during the three decades between 1859 and 1890, Darwin’s Origin of Species sold only some thirty-nine thousand copies in the six English editions.)7 By 1912 Die Welträthsel had been translated, according to Haeckel’s own meticulous tabulations, into twenty-four languages, including Armenian, Chinese, Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Esperanto.8 The young Mohandas Gandhi had requested permission to render it into Gujarati; he believed it the scientific antidote to the deadly wars of religion plaguing India.9

Haeckel achieved many other popular successes and, as well, produced more than twenty large technical monographs on various aspects of systematic biology and evolutionary history. His studies of radiolarians, medusae, sponges, and siphonophores remain standard references today. These works not only informed a public; they drew to Haeckel’s small university in Jena the largest share of Europe’s great biologists of the next generation, among whom were the “golden” brothers Richard and Oscar Hertwig, Anton Dohrn, Hermann Fol, Eduard Strasburger, Vladimir Kovalevsky, Nikolai Miklucho-Maclay, Arnold Lang, Richard Semon, Wilhelm Roux, and Hans Driesch. Haeckel’s influence stretched far into succeeding generations of biologists. Ernst Mayr, one of the architects of the modern synthesis of genetics and Darwinism in the 1940s, confessed that Haeckel’s books introduced him to the attractive dangers of evolutionary theory.10 Richard Goldschmidt, the great Berlin geneticist who migrated to Berkeley under the treacherous shadow of the Nazis in the 1930s, later recalled the revelatory impact reading Haeckel had made on his adolescent self:

I found Haeckel’s history of creation one day and read it with burning eyes and soul. It seemed that all problems of heaven and earth were solved simply and convincingly; there was an answer to every question which troubled the young mind. Evolution was the key to everything and could replace all the beliefs and creeds which one was discarding. There were no creation, no God, no heaven and hell, only evolution and the wonderful law of recapitulation which demonstrated the fact of evolution to the most stubborn believer in creation.11

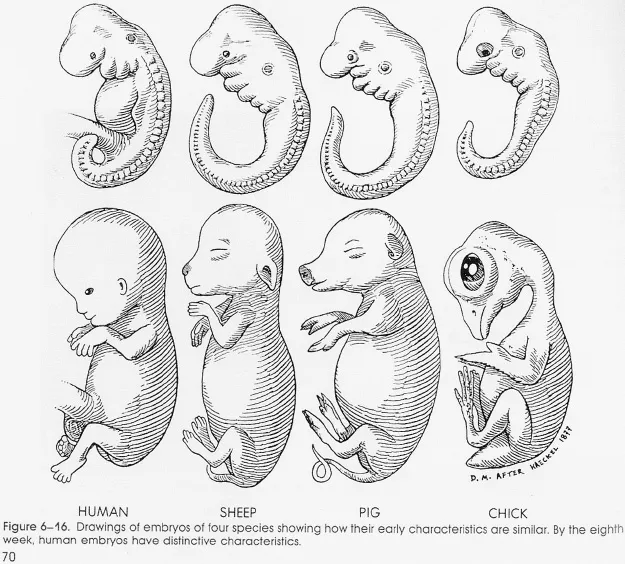

Haeckel gave currency to the idea of the “missing link” between apes and man; and in the early 1890s, Eugène Dubois, inspired by Haeckel’s ideas, actually found its remains where the great evolutionist had predicted, in the Dutch East Indies.12 Haeckel formulated the concept of ecology; identified thousands of new animal species; established an entire kingdom of creatures, the Protista; worked out the complicated reproductive cycles of many marine invertebrates; identified the cell nucleus as the carrier of hereditary material; described the process of gastrulation; and performed experiments and devised theories in embryology that set the stage for the groundbreaking research of his students Roux and Driesch. His “biogenetic law”—that is, that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny13—dominated biological research for some fifty years, serving as a research tool that joined new areas into a common field for the application of evolutionary theory. The “law,” rendered in sepia tones, can still be found nostalgically connecting contemporary embryology texts to their history (figs. 1.1 and 8.18).14

Haeckel, however, has not been well loved—or, more to the point, well understood—by historians of science. E. S. Russell, whose judgment may usually be trusted, regarded Haeckel’s principal theoretical work, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (General morphology of organisms, 1866), as “representative not so much of Darwinian as of pre-Darwinian thought.” “It was,” he declared, “a medley of dogmatic materialism, idealistic morphology, and evolutionary theory.”15 Gavin De Beer, a leading embryologist of the first half of the twentieth century, blamed Haeckel for putting embryology in “a mental strait-jacket which has had lamentable effects on biological progress.”16 Peter Bowler endorses these evaluations and further judges that the biogenetic law “illustrates the non-Darwinian character of Haeckel’s evolutionism.”17 Bowler believes Haeckel’s theory of evolution ideologically posited a linear and progressive trajectory toward man. Haeckel, he assumes, did not take seriously Darwin’s conception of branching descent. Daniel Gasman has argued that Haeckel’s “social Darwinism became one of the most important formative causes for the rise of the Nazi movement.”18 Stephen Jay Gould concurred, maintaining that Haeckel’s biological theories, supported by an “irrational mysticism” and a penchant for casting all into inevitable laws, “contributed to the rise of Nazism.” Like Bowler, Gould held that the biogenetic law essentially distinguishes Haeckel’s thought from Darwin’s.19 Adrian Desmond and James Moore divine the causes of Haeckel’s mode of thinking in “his evangelical upbringing and admiration for Goethe’s pantheistic philosophy [which] had led him to a mystical Nature-worship at the University of Würzburg.”20 German historians of recent times have treated Haeckel hardly more sympathetically. Jürgen Sandmann considers Haeckel and other Darwinists of the period to have broken with the humanitarian tradition by their biologizing of ethics.21 Peter Zigman, Jutta Kolkenbrock-Netz, and Gerd Rehkämper—just to name a few other German historians and philosophers who have analyzed Haeckel’s various theories and arguments—have rendered judgments comparable to their American and English counterparts.22

Fig. 1.1. Depiction of different embryos at two stages of development “after Haeckel.” (From Keith Moore’s Before We Are Born, 1989.)

Could this be the same scientist whom Darwin believed to be “one of the few who clearly understands Natural Selection”? The same individual whom Max Verworn eulogized as “not only the last great hero from the classical era of Darwinism, but one of the greatest research naturalists of all times and as well a great and honorable man”?23

Ernst Haeckel was a man of parts. It is not surprising that assessments of him should collide. I believe, however, that Darwin and Verworn, his colleagues, exhibited a more reliable sense of the man. This is not to suggest, though, that other of his contemporaries would not have agreed with the evaluations made by the historians I have cited. The philosophers, especially the neo-Kantians, were particularly enraged. Erich Adickes at Kiel dismissed Die Welträthsel as “pseudo-philosophy.”24 The great Berlin philosopher Friedrich Paulsen erupted in molten anger at the book and released a flood of searing invectives that would have smothered the relatively cooler judgments of the historians mentioned above. He wrote:

I have read this book with burning shame, with shame over the condition of general education and philosophic education of our people. That such a book was possible, that it could be written, printed, bought, read, wondered at, believed in by a people that produced a Kant, a Goethe, a Schopenhauer—that is painfully sad.25

The Swiss zoologist Ludwig Rütimeyer stumbled across one of Haeckel’s more crucial lapses of judgment and instigated a charge of scientific dishonesty that would hound him for decades.26 And, of course, Haeckel’s continued baiting of the preachers evoked from them an enraged howl of warning about “the depth of degradation and despair into which the teaching of Haeckel will plunge mankind.”27 Contemporary creationists and those advocating intelligent design have heeded the warning; they have ignited thousands of websites in an electronic auto-da-fé in which Ernst Haeckel’s reputation is sacrificed to appease an angry God.

Haeckel’s evolutionary convictions, fused together by the deep fires of his combative passions, kept the human questions of evolution ever burning before the public, European and American, through the last half of the nineteenth century and well into ours. The controverted implications of evolutionary theory for human life—for man’s nature, for ethics, and for religion—would not have the same urgency they still hold today had Haeckel not written.

The measure of Haeckel is usually taken, I believe, using a one-dimensional scale. His acute scientific intelligence moved through many diverse areas of inquiry—morphology, paleontology, embryology, anatomy, systematics, marine biology, and his newly defined fields of phylogeny, ecology, and chorology (biogeography)28—and to all of these he made important contributions. But more significantly, through a deft construction of evolutionary processes, he reshaped these several disciplines into an integrated whole, which arched up as a sign of the times and a portent for the advancement of biological science. He anchored this evolutionary synthesis in novel and powerful demonstrations of the simple truth of the descent and modification of species. Haeckel supplied exactly what the critics of Darwin demanded, namely, a way to transform a possible history of life into the actual history of life on this planet. Certainly he merited Darwin’s accolade and was, I believe, the English scientist’s authentic intellectual heir. But Haeckel, needless to say, was not Darwin. His accomplishments must be understood as occupying a different scientific, social, and psychological terrain, through which passed a singular intellectual current that flowed powerfully even into the second half of the nineteenth century, namely, Romanticism.29

Both by intellectual persuasion and temperament, Haeckel was a Romantic. His ideas pulsed to the rhythms orchestrated by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, and Matthias Jakob Schleiden. They, and other similarly disposed figures from the first half of the century, inspired Haeckel in the construction of his evolutionary morphology. They had proposed that archetypal unities ramified through the wild diversity of the plant and animal kingdoms. Such Ur-types focused consideration on the whole of the creature in order to explain the features of its individual parts. When the theory of the archetype became historicized in evolutionary theory, it yielded the biogenetic law, the lever by which Haeckel attempted to lift biological science to a new plane of understanding. The Romantic thinkers to whom Haeckel owed much regarded nature as displaying the attributes of the God now in hiding; for them, and Haeckel as well, it was Deus sive na...