![]()

| WALLS, JETTIES AND TOWERS How to date the main structure |

When looking at a building, there are clues to its age from the way the structure has been designed and constructed. The Saxons and Normans made their stone walls very thick to counter the load from the roof, so their round arched doors and windows were set in deep openings and their buildings tended to be tall and narrow. Masons soon realised that a pointed arch was more flexible than a round, and that by adding buttresses along the walls, the thrust from the roof could be countered. This meant that walls became thinner and windows larger. From the late 12th century, these new ideas resulted in ever more graceful Gothic churches, chapels and halls. Carpenters also developed new methods of building the roof structure with horizontal tie beams and braces which allowed them to span wider spaces without pushing the walls outwards. This culminated in the ingenious hammer beam roof with an open central section, the finest example of which is at Westminster Hall, London, which spans nearly 70ft.

From the late 16th century, the influence of the Renaissance, and an appreciation of Classical architecture, changed the approach to building design. Medieval structures had been asymmetric, with the function of each part shaping its form. Now buildings increasingly became symmetrical, with their shape controlled by mathematical proportions. This evolved into the elegant Classical buildings of the 18th century, with plain walls featuring rectangular windows, columns, and pediments and the roof hidden behind a parapet. Large buildings in the past had been of single room depth, arranged in a row or around a courtyard. From the late 17th century, they became double piled (two rooms deep), with corridors and hallways allowing both access and increased privacy.

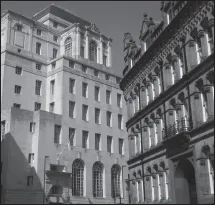

FIG 1.1: Most tall urban buildings were built with a rectangular body, as here on the right. But in the 1920s and 30s stepped blocks were a distinctive style for tall structures, as here on the left.

In the 19th century, new materials like Welsh slates and cast iron, along with developments in structural engineering, resulted in taller, wider buildings becoming quicker and more economical to build. The Gothic revival encouraged architects to design asymmetrical buildings with prominent, steep pitched roofs and walls filled with colour and pattern.

Towards the end of the century Arts and Crafts architects built houses which embraced the landscape rather than dominating it, with many built down a slope rather than having the site levelled first. Some of their buildings had ‘L’ shaped plans or were arranged around a courtyard. Buildings with two angled wings flanking the main entrance which formed a ‘Y’ shaped plan were used on some churches and houses in the early 20th century.

Concrete foundations, steel frames and carefully calculated trusses from the early 20th century permitted ever increasing width and height, and freed the exterior from bearing the load, so it could become just a cladding of glass or metal sheets.

THE MAIN BODY

FIG 1.2: A Medieval building had its parts shaped by their function, with little concern for its relationship with the other parts (left). Classical buildings had their facade and plan controlled by symmetry and mathematical proportions, derived from ruins in Ancient Rome and Greece (centre). When the Victorians revived Medieval Gothic architecture, they used asymmetry (right) and emphasised the function once again, as shown here by the windows on the tower lighting the steps.

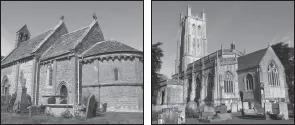

FIG 1.3: Churches often had a curved or polygonal apse at the east end in the 11th and 12th century with a tall, narrow body (left). From the 13th to 15th centuries (right) they typically had a square ended chancel (the space reserved for the clergy at the east end) with extra space provided by aisles to the side of a wider nave (the main body of the church for the congregation).

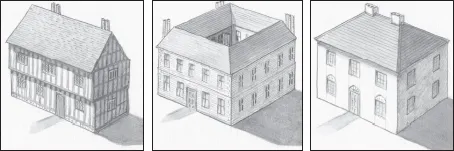

FIG 1.4: Single and double pile buildings: Most buildings up until the late 17th century were single piled, built one room deep (left). Larger structures could have this single room depth wrapped around a courtyard, so they appeared grander from the outside (centre). Double pile, two room depth, became standard for most buildings in the 18th century (right), although not for the smallest houses until the late 19th century.

FIG 1.5: Medieval halls were large open structures with an entrance passage at one end (left). In the 16th and 17th centuries, to gain greater privacy for the owner they were built as two storey structures or had a floor inserted into the old open space to create private chambers above a smaller hall (right).

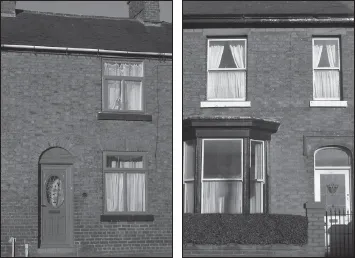

FIG 1.6: Victorian terraces were generally taller than earlier Georgian ones, as ceiling heights rose and additional floors were required. This can even be seen in small terraces where those from the first half of the 19th century had low roofs and windows tucked up tight under the eaves (left), but in the second half of the century they usually had steeper roofs and exposed lintels (right). Note also that these were stepped back from the road as it became desirable to increase privacy.

FIG 1.7: Symmetrical facades were designed for most buildings from the late 17th century, although some early attempts were often slightly off centre (top left). Strict symmetry and proportions controlled the facades of 18th century buildings (top right). Palace fronted terraces had the centre and each end of the row brought forward and highlighted with columns and pediments, so it appeared like a single grand building. They could be straight or crescent shaped and were fashionable in the late 18th and early 19th century (bottom).

FIG 1.8: The most important room or floor was usually emphasised on the exterior by large windows. The end where the lord of the manor sat in his Medieval hall was often illuminated by a tall window. In the 18th and early 19th century, the first floor or piano nobile had the tallest windows and was raised above a rusticated basement in the grandest buildings (right).

MAKING MORE ROOM

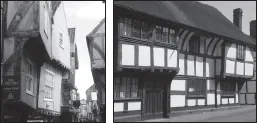

FIG 1.9: Jetties were a practical way of gaining more room and raising the status of an urban building (left), especially in the 15th and 16th centuries. Two jetties flanking a recessed centre, known as a Wealden house, are distinctive of the 15th and early 16th centuries (right).

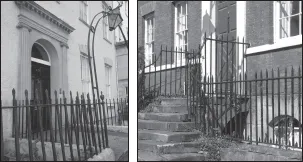

FIG 1.10: Basements became a common way of providing service rooms in buildings during the 18th and early 19th centuries. At first they were completely below ground (left), but by the late 18th century the upper half of the windows were above ground and the front door accessed up st...