CHAPTER 1

Mapping Jesus’s World

Let us try to imaginatively step into the world of ancient Jewish purity thinking. First, God has structured the world in a variety of ways, but perhaps most fundamental for Israel’s existence is its structure around two binaries: the holy and the profane, and the pure and the impure. The central text for this map came when God consecrated Israel’s priests—setting them apart from other Israelites. At that time, God informed the priests of their essential role in Israelite society: “You are to distinguish between the holy and the profane, and between the impure and the pure” (Lev. 10:10). While the majority of the writings within what Christians now call the Old Testament and what Jews call the Bible or Tanakh are not explicitly concerned with these four categories, by the time of Jesus, many extant writings were in some way indebted to this mapping of the world, as shown by their use of this language.

These categories should not be equated one with the other, as many readers of these texts have assumed. The word holy is not synonymous with the word pure. Neither is the word profane synonymous with the word impure. The category of the holy pertains to that which is for special use—in this sense, related to Israel’s cult and therefore to Israel’s God (Lev. 11:44; 20:7, 26; 22:32). For example, the Sabbath is holy (Exod. 31:14), as is the temple (Ps. 11:4). On the other hand, the category of the profane, a word that comes from the Latin profanus (“outside the temple”), refers to that which is secular or for common use. Here the English use of the word profane to refer to bad language might unfortunately lead to confusion. There is nothing dirty or impure or sinful about something being profane.

This first binary provides one map of the entire world—all things are either holy or profane. And most things within the world belong within the category of the profane. For example, six days of the week are profane, as are noncultic Israelite buildings. An object or a person cannot be both holy and profane at the same time. In itself, there is nothing wrong with or sinful about being profane. As we will see, though, it is dangerous and possibly sinful when something holy, such as the temple or the Sabbath, is profaned or when something profane encroaches upon something holy.

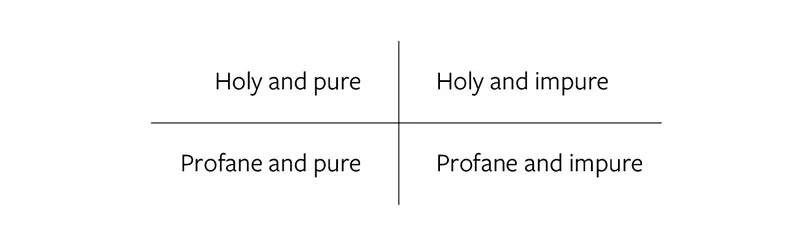

The second map of the world is constructed by the categories of the pure and the impure. Once again, all things in the world fit into one of these two categories: something is either impure or pure. And again, no thing or person can be both pure and impure at the same time. A profane object, such as someone’s house, can be either pure or impure. The same applies to holy objects—they can be either pure or impure. Israelite priests, who are consecrated (= holy), can be either pure or impure. To reiterate, the category of the holy is not synonymous with the category of the pure; neither is the category of the profane synonymous with the category of the impure. These are four distinct categories. And an Israelite person will always be characterized by two of these adjectives, existing in one of four possible states:

In priestly thought, the tent in the wilderness or the temple in Jerusalem is holy space inasmuch as God, who is holy and the source of all holiness, dwells there. The tent or temple is, in essence, a cordoned-off area that has a series of boundaries around it: the outer courtyard provides a protective barrier around the tent or temple, and the walls of the temple provide an additional barrier, permitting only priests to enter into the holy place. Even within the temple itself, an internal curtain protects the most holy place, into which only the high priest may enter and only once a year, on the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16).

What necessitates these barriers and what requires that God’s presence, his kavod or glory, be protected by a tent or temple is the existence of impurity in the world. In the realm of the profane, impurities can exist. There they can affect people without having immediate consequences. But Israel’s priests, at the instruction of their God, set up barriers to keep these impurities from entering where they must not—the Jerusalem temple, where Israel’s God dwells among humans. The various boundaries to the temple and the prohibitions regarding which people could not enter into sacred space were established in order to preserve God’s holy presence on earth, a presence threatened by impurities, to which Israel’s God was opposed. Were people to enter into sacred space with their impurities, they would be cut off from the people of Israel (Lev. 22:3). These boundaries, then, were meant not only to safeguard God’s presence but also to protect God’s people from the consequences of wrongly approaching God.

Because of this dual protective function, I would qualify Paula Fredriksen’s claim that compassion and purity have as much to do with each other as a fish and a bicycle. Fredriksen rightly aims to dismantle Christian scholarship that seeks to contrast Jesus’s compassion with the requirements of the ritual purity system. I would suggest, though, that compassion animates the Jewish purity system; it was a protective and benevolent system intended to preserve God’s presence among his people, a presence that could be of considerable danger to humans if they approached God wrongly.

For examples of how hazardous God’s presence could be (unrelated to ritual impurity per se), one need only consider two priests, Nadab and Abihu, who approached this God with strange fire and died as a result (Lev. 10). Or recall Uzzah, who wrongfully touched the ark of the covenant and died (2 Sam. 6). Access to sacred space was heavily restricted, not out of a lack of compassion but out of the belief that this holy God not only was merciful and loving but also was a powerful force that could be dangerous. The fact that Nadab and Abihu were priests and sons of Aaron matters not at all, nor does it matter that Uzzah piously meant to keep the ark of the covenant from falling to the ground. How much more would the unwitting or witting introduction of impurity into the realm of the holy endanger people? This depiction of God makes sense of the Israelites’ request that Moses speak to them on God’s behalf so that they would not have to endure the fear-inducing experience of encountering God directly (Exod. 20:18–21). Leviticus 15:31 nicely encapsulates the priestly concern over people coming too close to the tabernacle or temple while in a state of impurity: “Therefore, you shall separate the people of Israel from their impurity, so that they do not die by their impurity by defiling my tent which is in their midst” (cf. Num. 19:13, 20).

Contemporary Christians might compare this thinking to the way C. S. Lewis portrays Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Upon finding out that Aslan is a lion, not a man, Susan asks, “Is he quite safe? I shall feel rather nervous about meeting a lion.” To which Mrs. Beaver responds, “If there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just silly.” A young Lucy reiterates Susan’s question: “Then he isn’t safe?” Mr. Beaver then answers, “Safe? . . . Don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.” Israel’s priests did not believe that their God was some domesticated deity. Contrary to numerous modern caricatures, this depiction of God is not something unique to the Christian Old Testament—the God of the New Testament isn’t meek and mild either. Luke, for instance, relates the fatal consequences that Ananias and Sapphira experienced for lying to the early leaders of the Jesus movement: without warning, God killed them (Acts 5). Simply put, approaching the God of Israel in the wrong way is dangerous. It is no wonder then that the Gospel writers depict Jesus exercising a fierceness in relation to the Jerusalem temple and to what he perceives to be an impious use of the sacred space associated with God’s earthly presence (Mark 11:15–17; cf. Matt. 21:12–17; Luke 19:45–48; John 2:13–17).

Although humane, these ritual requirements meant that humans would need to keep their distance from God as long as they found themselves in a state of impurity. If impurities were to accumulate in God’s dwelling, God would be forced to abandon it. When Israelites allowed impurities to build up in the tent or temple, they suffered the consequences. The boundaries around the tent or temple functioned to protect both the inside (God’s presence) and the outside (any Israelite in a state of impurity) from the results of impure forces. Such thinking was commonplace in the ancient Mediterranean world. As Fredriksen puts it, ancient “gods tended to be emotionally invested in the precincts of their habitation, and they usually had distinct ideas about the etiquette they wanted obser...