eBook - ePub

Handbook on the Pentateuch

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

Hamilton, Victor P.

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 480 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Handbook on the Pentateuch

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

Hamilton, Victor P.

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

In this introduction to the first five books of the Old Testament, Victor Hamilton moves chapter by chapter through the Pentateuch, examining the content, structure, and theology. Hamilton surveys each major thematic unit of the Pentateuch and offers useful commentary on overarching themes and connections between Old Testament texts.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Handbook on the Pentateuch als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Handbook on the Pentateuch von Hamilton, Victor P. im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Theology & Religion & Biblical Criticism & Interpretation. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

Creation and the Fall

GENESIS 1–3

There are numerous ways in which the first book of the Bible may be outlined. Perhaps the simplest is:

- Primeval history (chs. 1–11)

- The creation (chs. 1–2)

- The fall (chs. 3–11)

- The cause (ch. 3)

- The effects (chs. 4–11)

- Patriarchal history (chs. 12–50)

- Abraham (chs. 12–25)

- Jacob (chs. 26–36)

- Joseph (chs. 37–50)

This outline accurately reflects the content of Genesis but fails to suggest any relationship between the parts or any progression in emphases. It is preferable to allow Genesis to outline itself and follow the units suggested by the text. These units are readily discernible.

- The story of creation (1:1–2:3)

- The generations of the heavens and the earth (2:4–4:26)

- The generations of Adam (5:1–6:8)

- The generations of Noah (6:9–9:29)

- The generations of the sons of Noah (10:1–11:9)

- The generations of Shem (11:10–26)

- The generations of Terah (11:27–25:11)

- The generations of Ishmael (25:12–18)

- The generations of Isaac (25:19–35:29)

- The generations of Esau (36:1–37:1)

- The generations of Jacob (37:2–50:26)

Thus Genesis is composed of an introductory section, followed by ten more sections, each introduced with the phrase “these are the generations of” (tôlĕdôt). Structurally, then, Genesis divides itself not into two sections (one on primeval history, constituting about a fourth of the book; one on patriarchal history, constituting about three-fourths of the book), but rather into two quite unequal sections: 1:1–2:3 (an introduction) and 2:4–50:26 (composed of ten subsections). And yet the primeval/patriarchal divisions cannot be totally laid aside, for one observes that the first five uses of the tôlĕdôt formula appear throughout 2–11, and the remaining five appear throughout 12–50 (or to be more exact, in the outline above, II–VI = 2:4–11:26; VII–XI = 11:27–50:26). Although there is no “these are the generations of Abraham,” his appearance at the end of VI (see 11:26) and his dominant role in VII make him a bridge figure between primeval and patriarchal history, between the origins of the nations of the earth and the origins of the chosen nation.

The movement in each of the last ten sections is from source to stream, from cause to result, from progenitor to progeny. That movement is described either through subsequent narrative after the superscription (II, IV, VII, IX, XI) or a genealogy that follows the superscription (III, V, VI, VIII, X).

The result created by this introduction-superscription-sequel pattern in Genesis is that of a unified composition, neatly arranged by the author (or the narrator or editor). Furthermore, the testimony of the text is to emphasize movement, a plan, something in progress and motion. What is in motion is nothing less than the initial stages of a divine plan, a plan that has its roots in creation. From the earth, Adam will come forward. From Adam, Abraham and his progeny will emerge. Eventually, out of Abraham, Jesus Christ will emerge. In the words of VanGemeren (1988: 70), “The toledot formula provides a redemptive-historical way of looking at the past as a series of interrelated events.”

Creation (1–2)

The first thing that strikes the reader of the Bible is the brevity (just two chapters) with which the story of the creation of the world and humankind is told. The arithmetic of Genesis is surprising. Only two chapters are devoted to the subject of creation, and one to the entrance of sin into the human race. By contrast, thirteen chapters are given to Abraham, ten to Jacob, and twelve to Joseph (who was neither a patriarch nor the son through whom the covenantal promises were perpetuated). We face, then, the phenomenon of twelve chapters for Joseph, and two for the theme of creation. Can one person be, as it were, six times more important than the world?

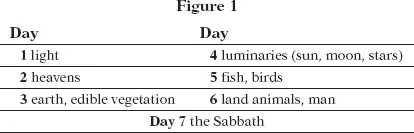

Nevertheless, our understanding of the Bible surely would be impoverished—rather, jeopardized—without these first two chapters. What are they about? A skeletal outline of the contents of 1:1–2:3 is helpful, as shown in figure 1.

It is obvious that the first six days fall into two groups of three. Each day in the second column is an extension of its counterpart in the first column. The days in the first column are about the creation (or preparation) of environment or habitat. The days in the second column are about the creation of those phenomena that inhabit that environment. Thus, on day one, God created light in general or light-bearers; on day four, specific kinds of light appear. On day two, God made the firmament separating waters above from waters below; on day five, God made creatures of sky and water. On day three, God first created the earth and then vegetation; on day six, God first made the creatures of land and then humankind. The climax to creation is the seventh day, the day of rest for God. The preceding days he called good. This one alone he “sanctified” (the only occurrence in Genesis of the important Hebrew root q-d-š, apart from the reference to Tamar, Judah’s daughter-in-law, as a “shrine prostitute” [38:21, 22 NIV]).

In addition to this horizontal literary arrangement, one can observe a fundamental literary pattern throughout all of Genesis 1. Using the language of Claus Westermann (1974: 7), we note this pattern:

- announcement: “and God said”

- command: “let there be/let it be gathered/let it bring forth”

- report: “and it was so”

- evaluation: “and God saw that it was good”

- temporal framework: “and there was evening and there was morning”

An alternative pattern is:

- introduction: “and God said”

- creative word: “let there be”

- fulfillment of the word: “and there was/and it was so”

- description of the act in question: “and God separated/and God made/and God set/so God created”

- name-giving or blessing: “and he called/blessed”

- divine commendation: “and it was good”

- concluding formula: “there was evening and morning”

The Relationship of 1:1–2:3 (or 4a) to 2:4 (or 4b)–25

Genesis 2:4–25 often has been described as a second creation story, although less so among biblical scholars today. Furthermore, it is suggested that not only is this a second story about creation, but also it comes from a different source than that of Gen. 1:1–2:3. Scholars who embrace the documentary hypothesis believe that the first creation story is the work of an anonymous Priestly editor or editors (P) around the time of the Babylonian exile (sixth century) or immediately thereafter. These scholars believe that the second creation story comes from a much earlier writer, usually designated as the Yahwist (J), an anonymous writer or writers from Jerusalem in the time of David and Solomon (the tenth century). Often, therefore, a scholar who subscribes to this hypothesis deals with the texts in their perceived chronological order of production, discussing 2:4–25 before 1:1–2:3.

There are several reasons for making this distinction. First, there is the different and, at points, contradictory account of the sequence of the orders of creation: the first sequence is vegetation, birds and fish, animals, man and woman; the second sequence is man, vegetation, animals, woman. Second, in the first sequence the exclusive name for the deity is “God” (Elohim), but in the second sequence it is “Lord God” (Yahweh Elohim). Third, in the first sequence God creates primarily by speaking: “and God said, ‘Let there be,’ and it was”—that is, creation by fiat. In the second sequence the emphasis is on God as potter or artisan: “the Lord God formed man of dust” (2:7 RSV); “out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field” (2:19 KJV); “and the rib . . . he made into a woman” (2:22 RSV). Fourth, in the first sequence the emphasis is on cosmogony: whence this world? In the second sequence the emphasis is on anthropology: whence humankind? Fifth, some interpreters draw a distinction between the poetic features of 1:1–2:3, with its use of stanzas and repetitions, and the narrative prose presentation of creation in 2:4–25.

Thus, the contention is that Genesis presents two originally independent creation stories, about five hundred years apart in origin. This phenomenon of “doublets” we will encounter again in the discussion of the flood story, where the unanimous opinion of literary and source critics is that originally there were two independent accounts of the deluge, again J and P, but with one distinct difference: the redactor (or redactors) of these opening chapters juxtaposed the two creation stories but spliced the two flood stories. As far as I know, attempts to provide a reason for this redactive distinction have not proved satisfactory.

In regard to the creation narrative, is it necessary to posit two mutually exclusive, antithetical accounts? Could 2:4–25 be a continuation of rather than a break in the creation story, “a close-up after the panorama of Genesis 1” (Ryken 1974: 37), or even simply an extended commentary on the sixth day of creation? The order of events in ch. 1 is chronological; the order of events in ch. 2 is logical and topical, from humankind to its environment. It is unnecessary to posit conflicting accounts about when God created human creatures of both sexes (in 1:1–2:3, at the same time; in 2:4–25, first the male and then later the female). As Barr (1998b) has argued, it is quite possible that in Gen. 1:26 God says, “Let us make a man in our image,” and that is followed by “male and [subsequently] female he made them” in 1:27. This seems to be the reading that Paul follows in 1 Cor. 11:7 when he distinguishes between man being the image and glory of God and woman being the glory of man: “A man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God; but the woman is the glory of man” (NIV). Most of the information in 2:4–25 is an amplification of 1:26–29. Chapter 1 is concerned with the world, while ch. 2 is concerned with a garden; one is cosmic, the other localized. God’s relationship to the world is in his capacity as Elohim, while his relationship to a couple in a garden is in his capacity as Yahweh Elohim; the first suggests his majesty and transcendence, the second his intimacy and involvement with his creation. Exactly why we must not posit a unity in Genesis 1–2 escapes me.

Theological Themes in Genesis 1–2

What the Themes Teach about God

The most obvious observation is the emphasis in these two chapters on the truth of God’s oneness. Instead of encountering a host of deities, the reader meets the one God. Unlike pagan gods, Go...